Sears Roebuck

...the company and its machines

Since the 1890s there had been a fad with large retailers and mail order houses to sell "own brand" sewing machines.

To do this they entered into contracts with established sewing machine manufacturers who would supply standard models but with the name of choice substituted for the normal brand name.

For the past 20 years I have been compiling a list of who actually made what and there are now over 5000 names in the file.

The situation is further confused in that retailers might switch makers at the end of a contract period and the same name would then appear on a completely different machine by another manufacturer.

Hawaii member Charles Law has attacked the problem from a different direction, specifically targeting the giant Sears Roebuck company and its branded products. GF

Company history

1890s -1950s:

Founded in 1893, Sears Roebuck & Co. was, next to Singer, one of the most important suppliers of sewing machines in North America from the 1890s through 1950s. In 1886, Richard Sears bought a supply of watches that a jewelry company had mistakenly shipped to a Minnesota jeweler. Seeing a chance to make a profit, Sears purchased the watches and sold them to his co-workers.

Seeing a great opportunity, Sears began the R.W. Sears Watch Company in Minnesota. With business growing briskly, he hired Alvah C. Roebuck, an Indiana watch repairman. Having concentrated on watches and jewelry up until 1894, the company then expanded its product lines, with sales of other items such as clothing, firearms, carriages, musical instruments, clocks, and sewing machines.

Sewing machines sales were a immediate success. A large part of this was due to the very low prices for which they sold their machines. Owing to the fact that Sears Roebuck was a mail order company, the overhead costs were comparatively low. Sears was able to sell high quality treadle sewing machines for between fifteen to twenty dollars far less than the forty to sixty dollars that retail dealers charged for equivalent models. A copy of the Singer Model 12 New Family was only nine dollars. Moreover, sewing machine sales were also only a minor component of the company's business. As such, the company was able to supply sewing machines to retail buyers at near-wholesale pricing for many years.

Featured in the 1894 catalog were copies of the Singer Models 12 and 48K and a vibrating shuttle model made by the Goodrich Sewing Machine Company of Chicago, Illinois. The two Singer machines were marketed as the 'Improved Singer' and 'Improved High-Arm Singer', in blatant violation of trademark laws. The 'Improved Singer' would appear in later catalogs as the 'Success' probably a result of threatened or actual litigation by the Singer Manufacturing Co.

The two Singer copies were June machines manufactured by the newly formed National Sewing Machine Company of Belvidere, Illinois. National also happened to be the supplier of sewing machines for Montgomery Wards & Co., Sears Roebuck & Co.'s chief competitor. However, unlike Montgomery Wards, which would continue to get all sewing machines from National until the sewing machine company met its demise in 1954, Sears would switch its suppliers several times in the following years.

In 1897, the company introduced a number of new models including another vibrating shuttle machine badged as the 'ACME' and manufactured by The Free Sewing Machine Company of Rockford, Illinois. 1899 saw the introduction of a vibrating shuttle sewing machine made by The Davis Sewing Machine Company of Dayton, Ohio. With a few exceptions, Davis would become the sole supplier of sewing machines to Sears until about 1912. It is during this time period that we have many of the Minnesota brand machines including the Models A, B, C, D, and K to name a few.

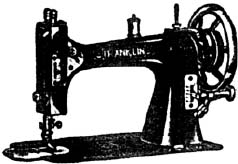

Beginning in 1911, the company introduced a number of machines based on Singer designs. They were the 'Franklin' (1911) and the 'Minnesota A' (1914), copies of Singer's Model 27/127 class manufactured by the Domestic Sewing Machine Company of Buffalo, New York. The 'Franklin' was decorated with Egyptian styled decalcomania, clearly in imitation of Singer's beautiful 'Memphis' decoration scheme. The 'Minnesota' was decorated in the same type of gold filigree used on the Davis -made 'Minnesota A.'

The Domestic company had been founded by William A Mack, inventor of the Mack-Patent High-Arm sewing machine the first truly modern high-armed lock stitch machine. However, by the 1910s the company had been reduced to manufacturing machines based on Singer designs. Sears likely changed its main supplier to Domestic because the Buffalo company could supply Singer copies. The only other retailer that sold more sewing machines in the United States was Singer. Both the Franklin and Minnesota Model A were near-exact copies of the Singer Model 27/127 (the most popular Singer model at the time). Sears Roebuck also marketed them as a lower priced, equivalent quality alternative to the pricey Singer. As such, the action was likely an attempt by Sears to increase its market share in the sewing machine business.

In the proceeding years, Sears slowly phased out sales of Davis sewing machines in favor of models made by Domestic and other manufacturers. These included the Minnesota L vibrating shuttle and the Economy rotary, both manufactured by the Standard Sewing Machine Company of Cleveland, Ohio. The last Davis model to be carried by Singer was the Minnesota K, which no longer appeared in the catalog after 1919. Davis would eventually go out of business about 1924, having apparently become dependent on supplying Sears with sewing machines over the previous twenty years for its main venue of income and unable to make up the loss from other sources.

In 1924, Sears Roebuck opened its first department store next to the Chicago mail-order facility. With the success of this new venture, Sears shifted its emphasis from a mail order company to a major retailer with a mail order catalog service.

By 1927, the company was operating a total of twenty-seven department stores. This new emphasis on retailing also meant higher overhead prices and consequently higher prices. The large disparity between Sears and retail prices that patrons had previously enjoyed slowly eroded. However, the service that the retailer offered inversely increased. Customers could bring their machine to the closest department store instead of having to ship their machine to the company or relying on the local sewing machine repairman.

In 1926, the White Sewing Machine Company of Cleveland, Ohio acquired Domestic , and would become Sears' sole supplier. White continued production of Domestic 's popular Franklin and also began supply of the 'Franklin Rotary', a standard White Model FR badged with the Sears brand name. In the following decades, White would become the sole supplier of machines. Next to Singer, White was the second most important sewing machine manufacturer in the United States. In terms of quality and durability, White sewing machines were every bit as good (and in some respects, better) than Singer models.

In the 1930s, the Domestic vibrating shuttle sewing machines, the Minnesota New Model A and the Model H, were phased out of production. The decade also saw the introduction of a variety of different rotary sewing machines based on the original White Model FR, some of which were only available as electrically driven models. In 1933, Sears introduced the extremely futuristic (and ugly) Franklin De-Luxe rotary. The machine was apparently not at all popular, lacking the tradition decalcomania and japanned finish. It later reappeared in Sears' 1938 catalog, renamed the Kenmore De-Luxe.

For whatever benefits the Second World War brought to industries recovering from the Great Depression, it dealt a catastrophic blow to sewing machine manufacturing. Like the other sewing machine companies, White halted sewing machine production in favor of war-material during the war. As a consequence, sewing machines disappeared from the catalog pages and department store floors of the Sears company. They would not reappear until about 1948, and by that time, would face a new rival cheap Asian import sewing machines.

As part of the Marshall Plan, the war-devastated economies of Europe and Japan would be rebuilt for civilian production. However, in the post war period, few nations beside the United States and the British Commonwealth would be able to purchase any of these goods. The United States paved the way by removing most all of its tarrifs that had protected the nation's industries from cheap overseas products. While this may have been good for the 'fight against communism' it destroyed America's production capabilities, beginning with the sewing machine industry. This would prove to be a prelude of what American (and later, European) industry had in store ahead, as electronics, clothing, furniture, and automobile manufacturers collapsed in the face of cheap Asian labor.

Sears' sewing machine line of the early 1950s consisted of various incarnations of the White Model FR and the old Singer Model 27 copy. By 1954, both Free/ New Home and National had gone out of business, leaving Singer and White the sole American home sewing machine manufacturers. Seeing what lay ahead, White undertook a joint venture with German manufacturer Pfaff and introduced a joint German-American designed zig-zag machine in 1954.

Unfortunately, by 1958 Sears had replaced its line of American and German-designed sewing machines with a selection of low-quality Japanese imports, retailing at basically the same price as their superior quality predecessors.

This move destroyed White , which had been the sole supplier of sewing machines to Sears for the past thirty years and had apparently, like Davis , become dependent on Sears Roebuck for the majority of its business.

Identification:

Perhaps the most challenging aspect of collecting Sears sewing machines is identifying them. This is especially true for machines made between about 1899 and 1929. During these 20 years, a large number of different models (from different manufacturers) were sold as the 'Minnesota.' For instance, there were five major versions of the Minnesota Model A, and in the case of the Davis -made machines, the manufacturer would make improvements quite often so that a Minnesota A from 1900 would not look much like one from 1905 or 1910. From research I have I have compiled the following table.

The 1890s

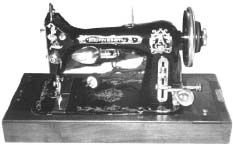

The "Success" was a re-badged version of the "Improved Singer" of 1894. The basic treadle model sold for the very reasonable sum of $8.95 in 1897

Manufactured by National, the "Improved Singer" was a clone of Singer's popular Model 12 New Family. This was one of the first machines Sears Roebuck carried, appearing in the 1894 catalog

The "Improved High-Arm Singer", was manufactured for Sears by the National Sewing Machine Company of Belvidere, Illinois. The machine was based on Singer's Model 48

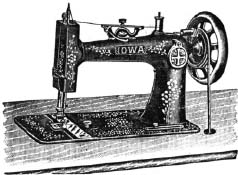

The "Iowa" is somewhat of an enigma. It was either manufactured by the American Sewing Machine Company, or by the National company (which is said to have acquired American sometime in the 1890s or 1900s). It is a badged version of the American No. 7 class sewing machine

The "ACME" was a high arm vibrating shuttle model made in the late 1890s by The Free Sewing Machine Company of Rockford, Illinois. The machine was a Free Model H badged with Sears Roebuck's brand

The early1900s

The "Howard" was a badged version of the National Model Vindex B vibrating shuttle sewing machine from the early 1900s

The "Home Queen" was a badged version of National's Model Vindex B Top Tension. Sears' main competitor, Montgomery Ward, carried the exact same model under the "Brunswick" label. Sears sold this model from about the late 1890s through early 1900s

The portable "New Queen" sewing machine manufactured by National in the early 1900s. The machine was available with either a cast iron or wooden base

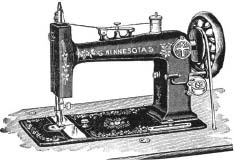

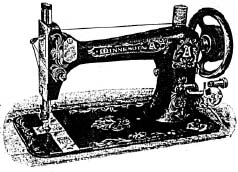

The "Minnesota A", a Davis Model E in Sears' livery. This was the top of the line machine manufactured by Davis. It featured well balanced ball bearing internal mechanisms which were claimed to allow it to run and sew more easily. This example is from the early 1900s

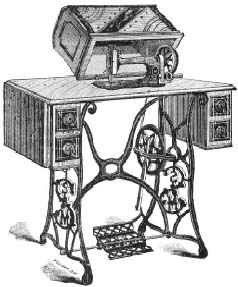

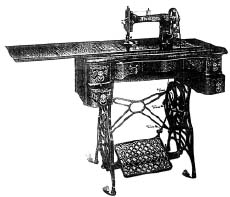

The early 1900s "Minnesota B" installed in a drop leaf type cabinet with five serpentine front drawers

1900s to 1910s

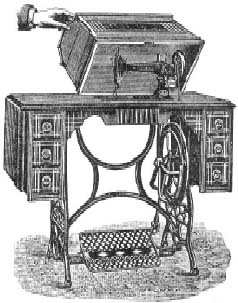

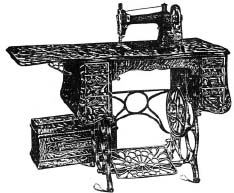

The "Minnesota A" installed in a fancy cabinet with drop leaf and gothic hood. This machine originally sold for about $16 in 1910

The "Burdick" was manufactured by the Davis Sewing Machine Company of Dayton, Ohio, in the early 1900s. The machine was later relabeled and sold as the Minnesota "B". 1900s-1910s

The Model A with the special, swinging wing pockets sold for about $19. It featured a drop head mechanism, four drawers, and wing pockets which provided storage for notions and accessories

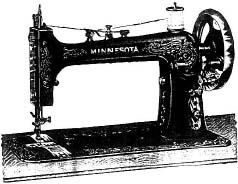

The "Minnesota A" from 1910. Although it appears to be a different (more streamlined) sewing machine, it is mechanically identical to its angular predecessor

The "Minnesota C" of 1904, manufactured by Davis. This machine was a badged version of the Davis Model M, which was basically a Model ME with a spring-plate top tension

The "Minnesota B" was a badged version of the Davis Model ME. It was a good running machine, but was not up to the quality of the "Minnesota A". It lacked ball bearings and did not use an independent type feed mechanism as with the "A" and top of the line Singer machines of the time as the Models 15, 27, and 66

The "Minnesota C" of 1908, also manufactured by Davis. Notice that the stitch length regulator has been relocated to the bedplate (from the upright portion of the arm)

The "Minnesota C", manufactured by Davis in the 1910s. It is mechanically identical to it's less aesthetically-pleasing predecessors

The "Minnesota S" was a renamed version of the "Minnesota B". Like the "B", it was a Davis Model ME in Sears livery. The machine was sold in the early 1910s.

The "Minnesota C" in a four drawer cabinet with skeletal type frames

The "Minnesota D", manufactured by Davis, was a badged Model T. It was available as either a portable or a convertible model (capable of being run by either treadle or handcrank). The machine was sold from the 1900s through 1910s

1920s

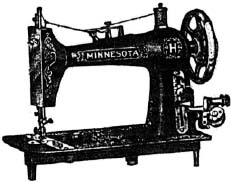

The "Minnesota H" was intended as a replacement in Sears' product line for the Davis "Minnesota K". This particular machine was sold throughout the 1920s

The "Economy", Sears Roebuck's first rotary model introduced about 1920. Manufactured by the Standard Sewing Machine of Cleveland, Ohio, it was replaced by the White "Franklin Rotary" about 1926

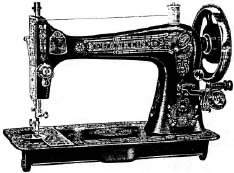

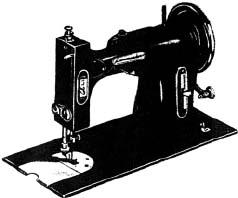

The "Franklin", manufactured by the Domestic Sewing Machine Company of Buffalo, NY, was introduced in 1911. An almost exact copy of the Singer Model 27/127, it uses the same shuttle,bobbin, needle,

The "Franklin Rotary", a badged version of the White FR class rotary sewing machine from about the mid to late 1920s

1930s

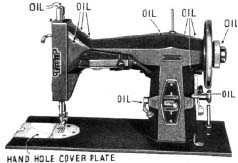

The "Kenmore" was introduced in 1933 and was a modernized version of White 's Family Rotary (Model FR). It featured a crinkle finish, forward and reverse sewing capability, and an integral sewing lamp. Unlike most of its contemporaries, it possessed no decorations

The "Minnesota M" was manufactured by White in the 1930s. It was basically a "Franklin" lacking the majority of its decorations

1950s

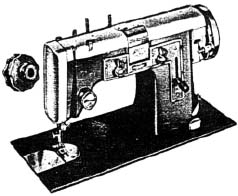

The "Kenmore 84" was, according to White , a product of American and Germany ingenuity. It was a zig-zag sewing machine which sold for the rather large sum of $239.95 in 1956

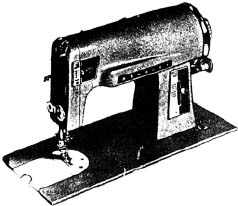

The "Commander 30" was a mid-1950s incarnation of the White Sewing Machine Company's FR rotary class selling for $43.95

The c1956 "Kenmore 58" was a White FR type machine which originally sold for $89.95 as a portable. This model, which bears more resemblance to a blender than a sewing machine, was capable of sewing forward and reverse and featured a built-in electric light

Perhaps it was an answer to Singer's popular Model 301 ? The "Kenmore 71", manufactured by White , was a rotary model made of aluminum and weighing only 17 1/2 pounds. It sold for a pricey $134.95 in 1956

After consultation and research, it turns out that the 71 was manufactured by the New Process Gear Company, in Syracuse, New York, rather than by White.

| NAME ON ARM | REMARKS | MANUFACTURER | CARRIED |

| Minnesota | New Home type shuttle | Goodrich | 1890s |

| Minnesota | Davis | 1900s | |

| Minnesota "A" | Same as Davis Minnesota | Davis | 1900S-1910s |

| Minnesota New "A" | New Davis model | Davis | 1910s |

| Minnesota "A" | Singer 27 clone | Domestic | 1910s-1920s |

| Minnesota New "A" | Like Domestic H but for disc tension | Domestic | 1920s |

| Minnesota "A" | Same as Domestic, above | White | 1920s-1930s |

| Minnesota "B" | Like Minnesota A but for disc tension | Davis | 1900s-1910s |

| Minnesota "C" | Leaf spring tension | Davis | 1900s-1910s |

| Minnesota "D" | Handcrank | Davis | 1900s-1910s |

| Minnesota "F" | Probably small machine | Davis | 1900s |

| Minnesota "H" | Domestic New A but leaf tension | Domestic | 1910s-1920s |

| Minnesota "K" | Same as newer Minnesota C | Davis | 1910s |

| Minnesota "L" | Standard | 1910s | |

| Minnesota "M" | Same as White Franklin | White | 1930s |

| Minnesota "S" | New version of Minnesota B | Davis | 1910s |

| Acme | Free | 1890s | |

| Belmont | Davis | 1900s | |

| Burdick | National | 1890s-1900s | |

| Burdick | Same as Minnesota B | Davis | 1900s |

| Economy | Version of Standard Rotary | Standard | 1920s |

| Edgemere | Same as Free Acme | Free | 1900s |

| Franklin | Singer 127 clone | Domestic | 1910s-1920s |

| Franklin | Singer 127 clone | White | 1920s-1930s |

| Franklin Rotary | White Rotary | White | 1920s-1930s |

| Homan | Davis | 1900s | |

| Howard | National | 1900s | |

| Iowa | American Round Bobbin VS. | American | 1890s |

| Kenmore | Standard | 1910s | |

| Kenmore | White Rotary | White | 1930s |

| Home Queen | National | 1900s | |

| New Queen | National | 1890s-1900s | |

| New Queen | Hand crank | National | 1900s |

| Imp Low Arm Singer | Singer 12 clone | National | 1890s |

| Imp High Arm Singer | Singer 48 clone | National | 1890s |

| Success | Singer 12 clone | National | 1890s |