A Timing Problem

The Rise and Fall of John Lester and His Sewing Machine in the American Civil War

NEW YORK, NY

John Henry Lester had done quite well for himself since arriving in New York in 1835 at the age of 20. He married his wife Ursula in 1841, started a family— Louisa and George— and had become an accomplished machinist and businessman. By 1850 he had his own factory and advertised in the New York based Scientific American:

John H. Lester manufacturer of Woodworth's Planing Machines, Steam Engines, and Boilers, Sugar Mills, Slide Lathes, Iron Planing Machines, Iron and Brass Castings of every description.

Office 192 Fulton St, NY Factory and Foundry at Hastings upon the Hudson 20 miles from the city by H.R. Railroad.

The Woodworth planer was patented in 1828, and the rights were sold to a cartel which collected royalties and obtained patent extensions. Lester was one of the few manufacturers in the area with the rights to produce and sell Woodworth planers, and this had made him a rich man. By 1854 his Scientific American ads showed the business located in Brooklyn.

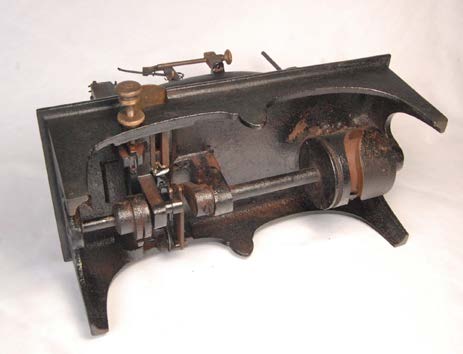

Figure 2

Front side of the Lester machine

Woodworth's Patent planning, tong uing Grooving machines – double machines plane both sides, tongue and groove at the same time saving half the time when lumber is required to be planed on both sides. Large assortment constantly on hand. Warranted to give entire satisfaction to purchasers. JOHN H. LESTER 57 Pearl St. Brooklyn, L.I.

In 1856, despite intense lobbying by the cartel and future Secretar y of State William H. Seward, Congress would not grant another renewal for the Woodworth patent. With the market opened up, John Lester's 1858 ad in the Scientific American showed the impact of the increased competition.

Woodworth Planing Machine Having over $40,080 now completed. I will sell from this time henceforth at very reduced price and am ready to construct any size not on hand at short notice. JOHN H. LESTER 57 Pearl St. Brooklyn, Long Island

Figure 1

Front side of the Lester machine

Lester began looking for a new venture to use his machinist's skills and factory equipment, and he could not help but see the growth of the sewing machine industry. Wheeler & Wilson, from his home state of Connecticut, were regular advertisers in the Scientif ic American. Singer offices were opening up all over the country. And he had heard of a new company that James Willcox was starting up in New York with a gentleman from Virginia named Gibbs. The sewing machine business was taking off and John Lester wanted to be a part of it.

The sewing machine Lester began manufacturing in 1858 was described in ads as Lester's Improved Shuttle Lock Stitch. It used a boat shaped shuttle and was not much different from other shuttle machines of the time. The patents on the machine were from A.B. Wilson in 1850 and 1854, and it was licensed under Howe's patents of 1846 and 1854. Lester had purchased a license from the "Sewing-Machine Combination" – the group formed in 1856 for Howe, Singer, Wheeler & Wilson, and Grover & Baker to pool their patents and license other companies to use them. The Combination also received a fee per machine, some of which was set aside for "prosecuting infringers." In addition to having the legal license to make his sewing machine, Lester would mention the Combination members by name in his ads as a form of product endorsement. More importantly, it would be the Combination license which would lead the Lester Manufacturing Company to Richmond Virginia.

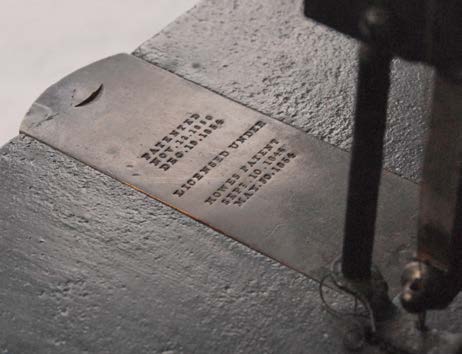

Figure 3

Shuttle cover plate showing Lester trademark

RICHMOND, VA

In 1857 Samuel Huffman was working in a Richmond store selling sewing machines when, like others in this fertile period, he had an idea for a better machine. It was slow going since Huffman had limited resources, but by 1860 his plans were starting to come together.

He had supporters in Richmond for his Old Dominion Sewing Machine Company, made a couple prototypes, and had a name for his machine, "Old Dominion" – the Virginia state nickname. When Huffman contacted the Combination to obtain a license Lester heard about it and decided to take a look at Richmond for himself.

In 1860 Richmond was the 25th largest city in the United States with a population of 37,910 – 23,595 white, 11,739 slaves, and 2,576 free African Americans. This was a far cry from New York City and Brooklyn, which together totaled over a million people. But Lester had found that New York was a crowded market for sewing machine makers, and Richmond offered him the opportunity to be the only sewing machine company in the South.

For Huffman, after years of planning, Lester's pa r t nersh ip wou ld br i ng t he resou rces needed to make his sewing machine company a reality. Lester and Huffman agreed to combine efforts.

Figure 4

Shuttle cover plate showing patents licensed

The birth of the Lester Manufacturing Company in Richmond was chronicled in the Richmond Daily Dispatch on March 31, 1860:

Southern Sewing Machines Lester Manufacturing Company Richmond VA

The subscribers have formed a joint stock company for the purposes of manufacturing

LESTER'S CELEBRATED TWO-THREAD, LOCK-STITCH, SHUTTLE SEWING MACHINES

which, from simplicity of construction and adaptation to all branches of needle-work, stands unrivaled, and we offer them to the public with full confidence, believing that a fair trial of the machine will satisfy all of our ability to furnish this valuable article in domestic economy, from OUR OWN FACTORY, that will prove in every respect equal to the best furnished by Northern manufactories.

These machines are manufactured and sold under legal rights from Elias Howe Jr., Wheeler & Wilson's Manufacturing Company, Grover & Baker's Sewing Machine Company, and I. M. Singer & Co.

A roster of 42 investor names followed – prominent citizens looking to make Richmond the "New Manchester of the South." Notably, Samuel Huffman's name was not on the list. Within a short time of Lester's arrival in Richmond it had become clear that Huffman's sewing machine was not ready for production – and probably never would be. Since Huffman had no other assets to offer the partnership Lester bought him out for "a few hundred dollars." Huffman's Old Dominion dreams were over -- he would never return to the sewing machine business.

While Lester had brought sewing machines and planers to sell in Richmond, he still needed to build a factor y a nd move his machinery, all while continuing to support the sale of Lester sewing machines through agents in the North. Scientific American, May 5th, 1860:

LESTER'S SEWING MACHINES – For manufacturing and for family use, as good as any in the market, manufactured under legal rights from Elias Howe, Jr., Wheeler & Wilson, Grover & Baker, I. M. Singer & Co., with their combined improvements, at prices from $50 to $110. Large commissions allowed to local agents to purchase and sell again. Agents wanted throughout the country, and especially in the South, as this machine is to be manufactured expressly at Richmond VA., as soon as the buildings which are now being put up are completed. Address the Lester Manufacturing Company, Richmond, VA., or J.H. LESTER, No. 57 Pearl-street, Brooklyn, N.Y.

With Lester's factory nearing completion, another sewing machine maker took an interest in joining him in Richmond; George B. Sloat from Philadelphia. Like Lester, Sloat had started out selling planers and switched to making sewing machines in 1858. Unlike Lester, Sloat felt his Elliptic didn't require a license from the Combination. Sloat would be one of the Combination's most determined adversaries, fighting a protracted legal battle in the courts while continuing to sell his Elliptic machines.

Sloat had been searching for another factory ever since his Philadelphia building burned down in August 1859, and he approached Lester about moving to Richmond. Lester was pleased to team up, Sloat would bring skilled workers for the factory and he had a proven record of selling sewing machines. The first ad for the combined Lester and Sloat operation appeared in the November 8th 1860 edition of the Richmond Daily Dispatch:

SLOATS CELEBRATED ELLIPTIC LOCK STITCH SEWING MACHINES are now manufactured by the UNION MANUFACTURING COMPANY, (Late Lester Manufacturing Company,) Of Richmond, Va., and are for sale at store No 231 MAIN STREET. These Machines, of home manufacture, are warranted the best in use. PLEASE CALL AND EXAMINE THEM.

"Union" was cur ious na me to use since Lester had been very careful to appeal to the Southern consumer, calling his machine the Plantation and placing the Virginia state motto on the slide plate – Sic Semper Tyrannis (Latin, literally meaning Thus, Always to Ty ra nts; a nd more commonly k now n as "Death to Tyrants.") Perhaps in using the Union name Lester was making a plea for everyone to get along, knowing that dis-union would not bode well for his business.

While the Union Manufacturing Company was selling both Lester's Plantation sewing machine and Sloat's Elliptic, it appears from the ads in the Richmond Daily Dispatch that Sloat handled the sewing machine sales while Lester sold the planers. The last Sloat ad appea red in t he R ichmond paper on December 29, 1860. Sloat's legal fight with the Combination had run its course. He was forced to assign the Elliptic machine rights to Nathaniel Wheeler. Sloat's arrangement called for the Wheeler & Wilson Company to supply him sewing machines to sell in Richmond, but the Civil War intervened.

Figure 6

Richmond capitol building, designed by Thomas Jefferson and Charles-Louis Clérisseau

THE CIVIL WAR

The American Civil War began on April 12, 1861 when Confederate artillery fired on Fort Sumter in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. This put Lester in a tough spot. He had moved his family and entire business operation to Richmond, and now he was stuck in the rebel capital with a company called Union. Lester tried to be neutral, but that meant that he was distrusted in both the North and the South.

With the outbreak of war Lester's factor y stopped making sewing machines and planers – in fact no ads had run since the end of 1860. Sloat's workers returned north and Lester tried to sell the business, but no one was buying from a "Yankee". Lester felt he had no choice but to stay in Richmond until he got paid – not realizing just how long that would take.

Lester began doing machinist work for a Virginia man, Samuel C. Robinson, and the factory took orders for pistols and carbines. (Lester would later say that he only worked on the machinery and didn't actually make the weapons – a distinction which would only help his conscience.) The factory turned out high quality weapons because Robinson was able to hire workers from the Harpers Ferry Armory. In the spring of 1863, fearing that Richmond, and his business, could be captured at any time, Robinson sold the arms factory to the Confederate government -- and Lester received a share of the proceeds in Confederate paper money only good in the South. (The factory building would not survive the war)

Figure 5

Back side of the Lester machine

On December 8 t h 1863 President Lincoln issued the Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstr uction, which offered a general pardon, with some exceptions, for rebels who would sign an oath of allegiance to the United States. Lester saw a chance to escape. The Confederacy was desperate for supplies, so he volunteered to go north to buy a ship and run the Union blockade. Instead, once Lester made it through enemy lines he went to the first Union unit he could find and signed an "amnesty oath". He was then allowed to travel to Washington, where he hoped to find help for his family.

In Washington, Lester explained his situation to Senator Foster of Connecticut, who interceded with an old friend from the Woodworth planer days, Secretar y of State Seward. Seward could see that Lester's amnesty oath was not going to expunge three years of arms making for the enemy. His advice was for Lester to "go to prison and lay there and appeal to no one as it was better for (you) and the government." Seward passed Foster and Lester along to Secretary of War Stanton, who had the authority to grant a pass for Lester's family. Stanton didn't trust Lester, so he sent him to see Major General Benjamin Franklin Butler in Fortress Monroe Virginia – just north of Norfolk on the peninsula. Stanton also sent Butler a letter of "introduction."

Washington D.C., Feb. 5, 1864

Major-Gen. Butler

I have given a pass to-day to a man lately from Richmond to visit you. His name is J. H. Lester. He is a Northern man, formerly from Connecticut and afterward from New-York, and was a partner of Sloat the planing machine man. They went to Richmond in 1860, he says, to carry on the making of planing machines, but their establishment has during the whole war been used for making arms, and I suspect that was the business for which he went to Richmond. He says he has sold out and has $250,000 worth of cotton at Wilmington. He has an authority and contract with the rebel War and Navy Departments to purchase a ship and run the blockade with supplies at certain dates. He got through our lines at Martinsburg and came on to Washington preceded by a fellow-companion whom he was to meet at Washington, but says he cannot find him. He wanted to get his wife and children through by a flag of truce but I have refused a permit. Lester is evidently a man of unusual ability and knows everything about the rebel government and its condition, but discloses nothing of any importance, and he certainly has its full confidence. I distrust him and his object, but have concluded to let him visit you so as to ascertain more clearly what he is about. If he has tired of the rebel cause and wants to leave it there may be no objection to his doing so, but if, as I suspect, he is only seeking to get his family into a place of security and continue his aid to the rebels then it may be necessary to take care of him. Let me know what conclusion you come to concerning him and take such measures as you may think proper.

EDWIN M. STANTON Secretary of War

Figure 7

Back side of the Lester machine

PRISON

Major General Benjamin Butler was notorious in the South stemming from his days as the military governor of New Orleans in 1862. His troops were having trouble getting the cooperation of the local populous, especially the ladies of the town who would spit, jeer, turn their backs and lift their petticoats. "These women evidently know which end of them looks best," Butler is reported to have said. When the abuse continued Butler issued General Order No. 28:

As the officers and soldiers of the United States have been subject to repeated insults from the women (calling themselves ladies) of New Orleans, in return for the most scrupulous non-interference and courtesy on our part, it is ordered that hereafter when any female shall, by word, gesture, or movement, insult or show contempt for any officer of the United States, she shall be regarded and held liable to be treated as a woman of the town plying her avocation.

The public out-cry was immediate and widespread, for there was nothing more important to a Southern gentleman than the honor of a Southern lady. General Butler would be forever known in the South as BEAST BUTLER.

Lester met with Butler in Fortress Monroe on February 6th 1864. Butler had received Stanton's letter and he had also been told that Lester left Richmond with $180,000. The money was the focus of Butler's questioning, and Lester recalls being told by an officer that he wouldn't be released until the $180,000 was turned over. (It was common for confiscated money and property to fail to make it into the government coffers) When Lester didn't produce the money he was returned to prison to await court-martial.

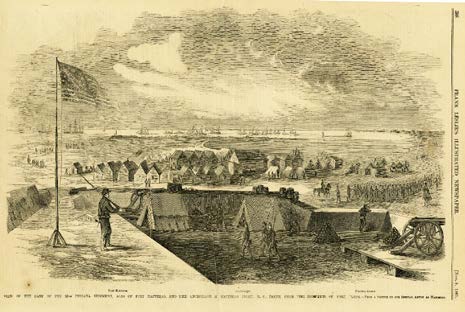

Figure 8

Dare County, Hatteras Island, N.C. "View of the camp of the 20th Indiana Regiment, also Fort Hatteras, and the anchorage at Hatteras Inlet, N.C., taken from the ramparts of Fort Clark." Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, November 9, 1861

Lester's arrest did solve one of his problems, showing the authorities in Richmond that he had tried to accomplish his supply mission, and giving them no reason to hold his family any longer. On February 22nd 1864, Lester's wife and two children were brought over on the "Flag of Truce" exchange boat operating across the James River between Fortress Mon r o e on t he Un ion side a nd A i kens Landing, Virginia in the South. This was the principal exchange point between the North and South for mail, prisoners of war, and refugees. The boat was probably the NEW YORK, a good sized paddle-wheeler.

Lester's court martial was conducted in April 1864. Union witnesses who knew Lester in Richmond testified that he was in the arms business, and the documents Lester brought through enemy lines incriminated him as an enemy agent. His defense, that he was forced to stay in Richmond and work for the rebels, did not convince the court. Lester was found guilty of "manufacturing arms for the enemies of the United States, giving information and endeavoring to give aid and comfort to the enemy, and treasonable and disloyal conduct." Lester was sentenced to 10 years in prison – at hard labor, wearing a ball and chain -- and forfeiture of all property. He was shipped off to prison in Fort Hatteras, on the outer banks of North Carolina. While in prison Lester wrote almost daily to Ursula – 94 letters survive – to keep up the family morale and to work for his release.

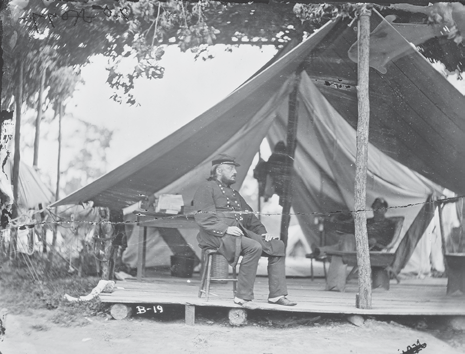

Figure 9

General Benjamin F. Butler, circa 1864

Ursula contacted Lester's political friends in Washington, and they were sympathetic to his plight, but no one was rushing to help an arms merchant from Richmond, especially with an election coming up. She wrote letters to the President Lincoln, and he did look into Lester's case; which resulted in this response from General Butler.

From General Butler Hd. Qtrs. Army of the James Sept. 28th, 1864, 7:35pm

To Abraham Lincoln, President United States, Washington

John H. Lester's property was confiscated to the use of the United States and he is in the hands of the Provost Marshal at Fortress Monroe. The record of confiscation will be found in General Orders No. 50, published May 8th, 1864. I will send for a copy and forward it as soon as possible.

We did not confiscate three hundred thousand (300,000) dollars worth of cotton which Lester had at Wilmington and (60,000) sixty thousand dollars in gold which he had in Canada.

B.F. Butler, Maj. Gen'l Comd'g

Ursula remained persistent, and eventually got to see the President – who was known to have a soft spot for crying women. (Unheard of for a modern day president, Lincoln was generous with his time in answering mail and holding regular open houses for private citizens – he called them his "public-opinion baths") With the 1864 election won and the war nearly over, President Lincoln issued a pardon for Lester – who's last letter from prison was dated April 6th 1865. On April 9th 1865, at Ford's theater in Washington, John Wilkes Booth shot President Lincoln, leapt from the balcony, and shouted, "Sic Semper Tyrannis."

Figure 10

"Ruins in Richmond" Damage to Richmond, Virginia from the American Civil War. April, 1865

POST-WAR

Lester returned to Brooklyn to find that his real estate holdings had been sold off for back taxes, and none of his other assets had survived the war. He would enter the lubricating oil business in New York, receiving a patent for "Improved Oil for Lubricating Machinery" in 1866, and continued in this line of work for three decades. He would also obtain a patent in 1871 for an "Improvement in Sewing-Machines" relating to the lock-stitch shuttle, but he would never return to the sewing machine business. In 1875 he patented an "Improvement in Milk-Cans" which used screws and bolts to obtain a tight seal. His son George improved upon that patent with one of his own in 1877. But none of this brought Lester the personal or financial success that he had before the war.

Lester laid the blame on General Benjamin Butler, whom he felt had unjustly imprisoned him, robbed Ursula of $12,000 she had brought from Richmond under her petticoat, and ultimately caused them to lose their home in Brooklyn. L ester was obsessed with taking Butler to court, but most judges refused to hear the case because the actions occurred under wartime martial law, or the statute of limitations had run out. Finally, in 1887, Lester found a judge in New York willing to give him his day in court, and he sued General Butler for $100,000. That was a huge sum in those days and The New York Times sent a reporter to cover the trial.

For over 20 years Lester had been waiting to confront Butler – but the trial turned out to be a disaster. On the stand Butler eloquently laid out his defense – Stanton's letter, Lester's incriminating papers, witnesses in Richmond – and described how Lester had been properly tried by court martial, convicted, and imprisoned for aiding the enemy. Of course Lester's forfeited property was turned over to the government. Butler didn't profit from Lester's arrest. Only a presidential pardon could get him out of prison. Butler was just doing his duty.

Then it was Butler's turn to ask the questions, and his cross examination of Lester was worthy of the best Law & Order episode.

With great theatrics, Butler assailed Lester's "True Blue" claim, getting him to grudgingly admit that: yes, that was his bill of sale for slaves in Richmond; yes, that was his name on the Confederate citizenship document; yes, he had taken a rebel loyalty oath; and yes, he had been exempted from the Confederate military because he worked in an arms factory. The judge had heard enough. Lester was luck y he wasn't put back in prison. The $100,000 lawsuit against Butler was dismissed.

John Lester died on January 10th 1900 "while sitting in his chair" at his daughter's home in Brooklyn – Ursula had predeceased him in 1873. He was buried in New L ondon, C on ne ct ic ut. L ester 's obit ua r y, wh ich appeared in the Brooklyn Eagle, was "culled from a story prepared by him recently." While it has numerous factual errors and omissions, it is interesting to note that Lester was most proud of being "a machinist and inventor, being the pioneer maker of sewing machines, his being the Lester lock stitch machine, the four motion feed, which was his special patent, being now in use on all machines."

EPILOGUE

The Lester sewing machine was in production from 1858-1861 and was sold by agents around the country. While it wasn't a revolutionary machine it did function well in competition with other machines. The Richmond Daily Dispatch reported in their November 1, 1860 edition on the list of premiums awarded at the Seventh Annual Exhibition of the Virginia Mechanics Institute which closed on the night of the 31st Oct. 1860.

Class No. 5 – Sewing Machines

To Wheeler & Wilson's Sewing Machines, Silver Medal

To the Lester Manufacturing Company, for Sewing Machines, First Class Diploma

To Grover & Baker's Sewing Machines, First Class Diploma

Figure 7

Underside of the Lester Machine

Additionally, Lester's sewing machine was still in demand after production had ceased, as evidenced by this Richmond Daily Dispatch ad from January 2, 1865:

WANTED. – A lady having a Lester Plantation Sewing-machine can find steady employment. Apply at P.H. Keach's store, between Eight and Ninth, on Main street.

Lester had the sewing machine, the financial resources, and the business talent to be successful in the sewing machine business. As the only sewing machine company in the South, Lester's machine had an advantage for transportation costs and the support of the local community. Once established, one could foresee Lester continuing to make improvements and innovations for long term growth. But he couldn't overcome his timing problem. Once the Civil War began, neither the South nor Lester's sewing machine would rise again.

Bibliography

Brooklyn Eagle, January 11, 1900, John Henry Lester Obituary

Richmond Daily Dispatch Newspaper 1859-1865

Holzer, Harold. Dear Mr. Lincoln: Letters to the President, Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, New York, 1993

The New York Times, February 15-18, 1887

Cooper, Grace Rogers. The Sewing Machine: Its Invention and Development, Published by t he Smithsonian Institution Press For The National Museum of History and Technology, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 1976

John H. Lester collection, Manuscript number 93833 containing 161 items, The Connecticut Historical Society Museum, One Elizabeth Street, Hartford CT 06105

Marshall, Jesse Ames. Private and Official Correspondence of Gen. Benjamin F. Butler during the period of the Civil War, Volume V – August 1864March 1868 – Copyright 1917

Scientific American, New York, NY, 1850-1870

Sewing Machine Times, New York, Issues March 25, 1902; May 10, 1906; May 25, 1906; June 10, 1906; June 25, 1906; and December 10, 1909, provided by the Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.

Trefousse, Hans L. Ben Butler: The South Called Him BEAST, New York, Twayne Publishers, 1957

United States Patent Office patents #7,776 #12,116 #28,371 #52,301 #115,872 #170,094 Vintage Machinery Website, www.vintagemachin- ery.org, Manufacturer Class: Wood Working Machinery & Steam and Gas Engines, John H. Lester