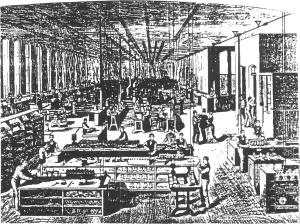

Brown and Sharpe's workshops where W&G's were made. This woodcut dates from 1879.

A History of the Willcox and Gibbs Company

by Graham Forsdyke

GETTING THE first Willcox and Gibbs machine from drawing board to the shop counter was an adventure beset with more engineering problems than most.

Willcox, who was in charge of production, approached the Providence, Rhode Island, company of Brown and Sharpe who were at that time makers of clocks, watches and measuring instruments, and asked if it would be interested in producing the new sewing machine.

This was, in some ways a strange request, for the company he had chosen was very small with only five lathes, one drill and a couple of planers. But he went along in late 1857 or early '58 with the prototype he had made himself in an attempt to get a costing on the job.

Brown and Sharpe were a little cagey, not wanting to commit to a price for work of which they had no experience. Eventually Willcox and Lucien Sharpe reached a compromise. The machine shop would produce a batch of 12 machines and then the cost could be accurately gauged.

To hedge his bets Sharpe wanted an agreement whereby Willcox would pay $3 per day during the development time. What's more, Sharpe wanted to build the machines using specially-made dies and tooling rather than as one-offs. Willcox also had to agree to pay for this work even if the machine was not a commercial success.

This idea of special tooling and, therefore, the complete interchangeability of parts, almost led to the downfall of the project before the first machine was finished.

Work began in March 1858 when the first drawings were made and soon the local New England Bull Company was busy on the frame castings.

About four of Brown and Sharpe's men, aided by Charles Gibbs, worked full time to produce the tools which would eventually make the sewing-machine parts, but at the end of May, Lucien Sharpe had to write to Willcox and admit that this work was taking far longer than expected.

Perhaps to encourage the manufacturer, Willcox upped his order to 100 machines of which 50 were to be of the type already being worked and 50 be of a smaller model. It's not known at this time whether the machine we know today is the larger or smaller version.

By the end of July the letters from Sharpe to Willcox were a little more optimistic, speaking of the end of the job being in sight, and of buying new machines to hasten things along. Still no price was given.

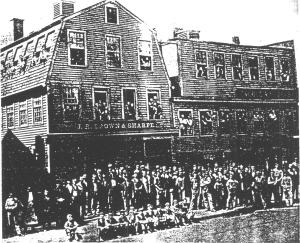

Brown & Sharpe's factory in Providence Rhode Island in the 1860's. The workers hanging out of the windows on the upper floors are proudly displaying Willcox and Gibbs machines for the photographer.

Then more snags cropped up. When iron castings cool they can often develop "chill spots" where the material is very hard. This happened to the Bull Company castings, and to save wear on drills and reamers, all the castings had to be annealed to remove the hard spots.

This, plus other problems, led Sharpe to write to Willcox again in September saying that he was very much discouraged over how the job was going, that more work was still being done on tooling than on the actual machines and that it would still be many weeks before the first batch was finished.

Perhaps Willcox's patience was wearing a little thin, for he remonstrated with Sharpe reminding him of their original production target date of many weeks previous.

In his defense Sharpe replied that the extra time had been taken getting things right and had they rushed an imperfect machine onto the market - as other manufacturers had done - the new company's reputation could have been destroyed at birth.

When the figures were finally totaled, it was found that Brown and Sharpe had spent 10 times its original budget just on the tooling for the machines.

But in October 1858 it all came together. Sharpe wrote to Willcox saying that the first 50 machines were on the final assembly benches and that the firm was now able to produce at the rate of 5000 per year. Fortunately, for all concerned, the machine was an instant success, and the small tool room quickly became a factory, continuing to make the W&G machines well into the 1970s.

Brown and Sharpe continued with its instrument business and developed a world-famous name for selling specialised machine tools to other sewing-machine manufacturers.

Among those who worked on Willcox and Gibbs machines at the Brown and Sharpe factory was one Henry Leland who was in charge of the sewing-machine department from 1878 until 1890.

Leland went on to devote his skills that he had learned on sewing machines to forming the prestigious Cadillac Car Company - the Rolls Royce of American automobiles.

With acknowledgements to "From the American System to Mass Production" by David Hounshell

Copyright Graham Forsdyke, ISMACS