The following account of the life of James Edward Allen Gibbs (unearthed by Bernard Williams) was published 10 years ago in The Virginia Cavalcade, a quarterly issued by the Virginia State Library and distributed to those interested in local history.

James Edward Allen Gibbs

by Anne Knox

James E. A. Gibbs, from a photograph taken about the time he invented his sewing machine.

ON THE DIVIDING LINE between Augusta and Rockbridge counties lies Walnut Grove, home of Cyrus Hall McCormick, inventor of the reaper. McCormick's invention assured him of lasting fame and recognition, but in a nearby village lived another inventor whose accomplishments were overshadowed by his competitors and whose work is little remembered outside his native Rockbridge county.

James Edward Allen Gibbs invented a sewing machine and founded a company to market it which is still in existence today. He is the only inventor outside of the New England states to produce a sewing machine. Yet Elias Howe and Isaac Singer are the names usually associated with the history of the early sewing machine and few have ever heard of James Edward Allen Gibbs.

Born three miles from Raphine in Rockbridge County on August 1, 1829, James Gibbs was the son of Richard and Isabella Poague Gibbs. Richard Gibbs, who was born in Connecticut and raised in Vermont, came to Fairfax County, Virginia, about 1815, bringing the first wood-carding machinery seen in the commonwealth.

He established his carding business on Bull Run but it did not prosper. He then moved to Rockbridge County and opened a carding business there. This mill was destroyed by fire in 1845. Gibbs worked for his father in the summers until the mill burned, and then left home, at age 16, to seek his fortune.

From 1845 until 1856 when he patented his sewing machine, Gibbs worked at various occupations and in several different locations. For awhile he rented a building and operated a carding mill in Lexington, but finding himself debt ridden, he left there in the early 1850s and went to Huntersville in Pocahontas County, now in West Virginia. Gibbs became a partner in another carding business, but sold his interest when that business, too, proved to be unsuccessful.

He realised that the large woolen factories that were coming into existence would supersede small carding mills. In Huntersville, however, Gibbs made his first invention, a labour-saving device for carding wool that "reduced the cost of operation at least 75 per cent". Having no money to pursue the matter, he did not patent the machine.

After leaving the carding business, Gibbs engaged in a variety of activities. He joined a surveying team in Randolph County, also in present-day West Virginia. On a surveying expedition he suffered a serious injury when, while cutting down a small pine tree, his ax slipped, cutting through his right knee cap. His companions took him to the home of Alexander Logan at Mingo Flat where for six months the Logan family, and especially William Logan, nursed him through to his recovery.

After the Civil War, when fortune had favoured Gibbs and taken everything from William Logan, Gibbs aided Logan in establishing a store at Midway, Virginia. The knee injury, however, prevented Gibbs from resuming his career as a surveyor and he became a carpenter and a millwright.

The actual patent model, now in Washington

In the winter of 1851-52, he built a grist and sawmill for Colonel Samuel Given in Nicholas county. While engaged in this project, he met Colonel Given's daughter, Catherine. The dark-haired young man with the big nose and sharp blue eyes could not have been called handsome, but he had a strong personality, and a social nature that Catherine must have found charming for they were married on August 25, 1852.

Refusing his father-in-law's offer of 500 acres of land and the equipment to start a farm, Gibbs returned with his wife to Pocahontas County where he continued to work as a carpenter.

Elias Howe, William O. Grover, William E. Baker, Isaac Singer and others, patented sewing machines in the early 1850s and revolutionised the clothing industry. In 1855, Gibbs saw a woodcut of a Grover & Baker sewing machine in a newspaper advertisement. It was the first image of these new contraptions that he had seen and there was little to show him how it worked.

All that was shown in the woodcut was the top half of the machine. Nothing indicated that more than one thread was used to form the stitch or indeed how the stitches were made. Gibbs decided that only one thread was used and since his curiosity was aroused, he formed in his mind a method for producing a single thread stitch. He later described the experience, saying:

"As I was then living in a very out-of-the-way place, far from railroads and public conveyances of all kinds, modern improvements seldom reached our locality, and not being likely to have my curiosity satisfied otherwise, I set to work to see what I could learn from the woodcut, which was not accompanied by any description.

I first discovered that the needle was attached to a needle arm, and consequently could not pass entirely through the material, but must retreat through the same hole by which it entered. From this I saw that it could not make a stitch similar to handwork, but must have some other mode of fastening the thread on the under side and, among other possible methods of doing this, the chain stitch occurred to me as a likely means of accomplishing the end.

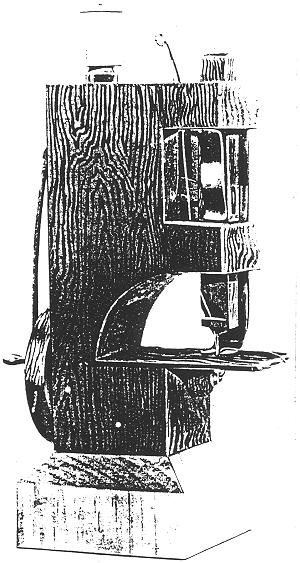

James Gibbs made this single thread, chain stitch sewing machine in 1855. He used this crude model to convince Willcox that is invention was useful and would reward investment. From this Gibbs and Charles Willcox produced the patent model.

I next endeavoured to discover how this stitch was or could be made, and from the woodcut I saw that the driving shaft, which had the driving wheel on the outer end, passed along under the cloth plate of the machine. I knew that the mechanism which made the stitch must be connected with and actuated by this driving shaft.

After studying the position and relations of the needle and shaft with each other, I conceived the idea of a revolving hook on the end of the shaft, which might take hold of the thread and manipulated it into a chain stitch. My ideas were, of course, very crude and indefinite, but it will be seen that I then had the correct conception of the invention afterwards embodied in my machine."

Gibbs's curiosity had been satisfied and he did not immediately pursue the matter because he did not realise the significance of his invention. However, in January 1856, when he was visiting his father in Rockbridge County, he happened to enter a tailor's shop and there saw a Singer sewing machine. Although Gibbs was impressed by the machine, he thought that it was "entirely too heavy, complicated, and cumbersome, and the price exorbitant". He remembered his own simpler invention and decided to work seriously on a less-expensive sewing machine.

James E. A. Gibbs was hampered in his attempt to perfect his sewing machine because he had to support his growing family and could only work on the invention at night and during inclement weather. In addition, he lacked proper tools and sufficient materials.

After months of effort, Gibbs succeeded in making, with his pocket knife, a crude wooden model. He made the needles for the machine himself and, according to his daughter, used the flexible root of mountain ivy to fashion the revolving looper which was the key to his invention. By April 1856, it was almost ready and Gibbs reportedly sold a half interest to John H. Ruckman, local owner of a sawmill, in order to pay to have the machine patented.

In Washington, D.C., Gibbs went to the Patent Office where he observed sewing-machine patent models as well as some of the machines then on the market. He patented two of the original features of his machine: the revolving looper which pulled up a definite quantity of needle thread proportionate to the length of the stitch (anticipating the latter-day automatic tensions), and a feeding mechanism which fed the work positively between two corrugated surfaces.

Gibbs could whittle and invent, but he realised that he could not market his machine alone. With his letters of patent in his pocket, he went to Philadelphia.

"I was in Philadelphia in 1857", he later wrote, "selling the first of my first two inventions in the office of Emery, Houghton and Company, when James Willcox came in. He remarked that he was a dealer in new notions and inventions, and he asked me to come to his little shop in Masonic Hall and build a model of my machine".

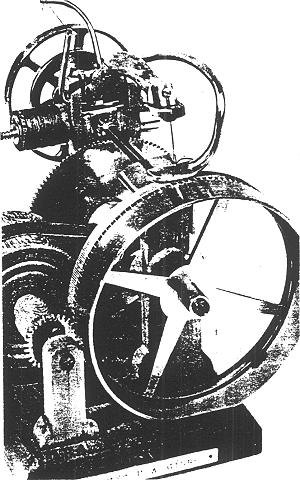

Gibbs worked with Willcox's son Charles to build a patent model and on June 2, 1857, he was awarded patent number 17,427 on his machine. As a result of the successful patenting of the machine, Willcox and Gibbs soon formed a partnership. In 1858, Willcox engaged thefirm of J. R. Brown and Sharpe of Providence, Rhode Island, to produce the sewing machines and the first ones were manufactured in November 1858. To market their machine, Willcox and Gibbs opened an office at 658 Broadway in New York City the following year.

The principle behind the machine was simple. As the machine descended through the cloth, the hook, located beneath the table or work plate, formed the loop from the needle thread, and while the hook rotated, it held the loop open as the machine fed the cloth forward until the needle made its next descent through the loop held open by the hook. When the needle came down through that first loop, the point of the hook caught the thread to make a second loop, "at which time the first loop was cast off and the second loop drawn through it, the first loop having been drawn up against the lower edge of the cloth to form a chain".

This method thus produced a chain-stitched seam. Such a simple and accurate mechanism as Gibbs's looper prevented the dropping of stitches which occurred with many other machines and which had brought the chain stitch into disrepute. Gibbs himself believed that one of the primary advantages of his machine was the greater elasticity and durability of his single-loop stitch over the conventional lock stitch.

Because Howe, Singer, and others had gotten into the sewing-machine field first, they held patents to certain standard features of the machine. Willcox and Gibbs had to be licensed and pay a royalty to Howe and the others for the use of the basic feed, straight needle, and other related parts of the machine. Nonetheless, Gibbs's invention was distinctive.

An article praising Gibbs's machine appeared in an 1859 issue of Scientific American and concluded that "one cannot but admire the beauty and accuracy of (the machine's) movements, and the entire absence of all noise, even when it is running at the rate of two-thousand stitches and upwards per minute". It pointed to the "good workmanship" of the Willcox and Gibbs machine and noted that it used interchangeable parts which could be easily and cheaply replaced if broken.

In addition, the machine came upon an "elegant stand that forms an ornament to a parlour". The writer in Scientific American also observed that the machine had been shown at the Franklin Institute Fair in Philadelphia, where a panel of judges gave it "the highest commendation" and an "eminently favourable report".

Not only had Gibbs successfully designed a simpler machine than the Singer model he had seen in Rockbridge County in January 1856, but his new sewing machine was also much less expensive. The Willcox and Gibbs machine, sold on a simple iron-frame stand, cost $50 at the end of the 1850s compared to a cost of $100 for the machines produced by Wheeler and Wilson, Grover & Baker, and Singer. Competition among sewing-machine manufacturers, however, was keen. Singer attempted to compete with Willcox and Gibbs but his first effort was a machine that was too light to attract the sewing public and it cost $100. Even an improved model which appeared in 1859 was higher priced at $75 than the Willcox and Gibbs machine.

In 1860, James E A Gibbs was 30 years old and had attained a modest degree of financial success. The Pocahontas County census of that year listed his occupation as a machinist and valued his real estate at $2,000, while his personal estate was worth $15,647. When the country went to war in 1861, however, James Gibbs left his business in New York to join the Confederate army. He joined one of the county's cavalry companies in 1861, but left the service after three weeks because he had contracted typhoid and pneumonia.

As the Federal army advanced into the Pocahontas County area in 1862, Gibbs moved his family to Rockbridge County. His purchase of 170 acres of land in Rockbridge County, which included his birthplace, was recorded in the county court clerk's office in December of that year. Shortly after returning to the Valley of Virginia, Gibbs was commissioned a lieutenant in the ordnance department and superintended the manufacture of saltpetre in Rockbridge County. Later in the war, when Major General David Hunter was laying the valley to waste, Gibbs and his 20 men were ordered out, and they fought in the battle of Piedmont on June 5, 1864.

When the fighting ended, Gibbs, like most other Southerners, found himself in financial straits. All he had was his ill health, 361 acres of land in Rockbridge County described as a "run-down farm", and the Confederate uniform that he was wearing. Because Federal military orders forbade the use of regulation buttons, Gibbs's were covered with cloth as were those of other Confederate soldiers.

Gibbs decided to go to New York to discover if anything remained of his sewing-machine business. Borrowing a broadcloth suit from a brother-in-law, he left Virginia in June 1865. His daughter, Ethel, recalled later that her father was followed from Jersey City to 658 Broadway in New York by a Northern detective who thought he was a man named "Gibbs from Louisiana, who had invented the famous mortar used by the Confederate Army". When Gibbs entered his old office, the detective evidently realised he had the wrong man. James and Charles H. Willcox greeted Gibbs with open arms and told him that they had deposited $10,000 in the bank to his credit. The two Willcox men had not made it public that the credit was for a Confederate because the money would have been confiscated.

Despite the strides made in the postwar years, everything did not always go smoothly for Gibbs. When he attempted to get an extension of his patent on the Willcox and Gibbs sewing machine, the commissioner of patents claimed that Gibbs had engaged in the "rebellion" and thus his patent was invalid. Gibbs called upon 47 manufacturers and home users to make affidavits extolling the machine in order to justify the patent extension. At least 18 of the affidavits came from commercial establishments that were engaged in such manufactures as lace, embroideries, ladies' wear, umbrellas, shirts, shoes, wool hats, and all types of bags. Gibbs won his case, and his patent was renewed in 1872 to expire in 1878.

In the same year, 1872, Gibbs turned his attention to the southern market. In an advertising booklet that he had printed, it was noted that "the inventor has now opened an office in Richmond for the express purpose of placing his invention, which has and is benefiting the rest of the world, within the reach of the Southern people". Gibbs's machine was sold in Richmond at 28 North Ninth Street from 1872 until 1876.

Despite Gibbs's effort to develop a southern market for his domestic sewing machines, changing business conditions forced the company to shift its attention from machines made for home use. The Singer company captured a large share of the home market late in the 1870s and this, along with the Panic of 1873, forced Willcox and Gibbs to stop manufacturing machines for domestic use and expand the manufacture of machines for commercial use. The company developed machines for making straw hats, for sewing knit goods and, in 1899, the first lock-stitch machine which could perform simultaneous functions such as trimming the edges of fabrics, scalloping, zig-zagging and fringing.

In the postwar period, James E A Gibbs found himself in comfortable circumstances. In 1880, for example, Gibbs enjoyed a combined income of about $10,550 including over $9,000 in bonds and notes. He refused to become an officer of the Willcox and Gibbs company when it was incorporated in New York as a stock company in 1866. He preferred, as did his wife, to live in the two-story brick home he had built on his farm.

Christened Raphine Hall, from the Greek word raphis, meaning needle, the house was large and comfortable and included a wing where Gibbs worked on his old inventions as well as new ones. In 1883, he gave a right of way to the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad to build its line and the land for the station, which he also named Raphine.

Gibbs continued to work with his company until about 1886. During that time he traveled widely, especially in Europe, to promote the sales of the Willcox and Gibbs sewing machines. In addition, he continued to work at his inventions and received 25 patents in all on the sewing machine. Gibbs's final invention was a lock-and-clutch-driven bicycle which he did not patent.

After his retirement from business, Gibbs continued to travel during the winter months. He visited the warmer climates of the South, Texas, and Mexico for his health. In 1887, his first wife, Catherine, died of typhoid fever, and in 1893 he married Miss Margaret Craig of Augusta County. Gibbs had four daughters by his first wife, Florence, Cornelia, Ellabel and Ethel, but no children by his second wife.

In November 1902 Gibbs traveled to New York seeking an operation to correct a long-standing illness, but the doctors he visited advised against it. He then returned home where he died on November 25 of "a protracted illness with paralysis".

Shortly before he died Gibbs gave his analysis of the invention of the sewing machine:

"No useful machine ever was invented by one man; and all first attempts to do work by machinery, previously done by hand, have been failures. It is only after several able inventors have failed in attempt, that someone with the mental power to combine the efforts of others with his own, at last produces a machine that is practicable. Sewing machines are no exception to this."

James E A Gibbs was one of those "able inventors". Using his own ideas and those of others, he developed a successful sewing machine that was not only practical, but also formed an "ornament to a parlour".

It is perhaps ironic that the Willcox and Gibbs Company, which still exists today and which has grown to control five subsidiary companies, no longer makes a machine for the home.