A Tour of the Wheeler & Wilson Sewing Machine Factory

The woman depicted at the machine is a blind mute, Laura Bridgman, who is "operating it and guiding the work by her fingers alone."

An article in the March 1st edition of The Christian Weekly (New York) in 1873 bears the title "Sewing-Machines and How they are Made." The reporter had toured the Wheeler and Wilson Sewing Machine Co. factory in Bridgeport Connecticut in the fall of 1872. What little he gleaned from this experience is provided in the article -- but little it is indeed, and we would learn equally little from his report were it not for one fortuitous circumstance: the reporter was accompanied by a fine sketch artist, E.J. Whitney, an employee of the newspaper.

The reporter himself understood the import of the artist's sketches: often, instead of explaining what work is being done, he tells us to examine the pictures: "...to describe the processes would require a better mechanic than we are, and to understand them would require more mechanical knowledge than is possessed by most readers. We shall not undertake this task. We are here in a very humble position; it is that which the lecturer in a panorama plays. We shall only attempt to interpret Mr. Whitney's pictures."

While I'll provide only the more meaningful excerpts from the reporter's text below, the illustrations from the original article are reproduced in their entirety. Having said that, I'll note that there are some tidbits in the article which are not conveyed by the pictures!

The reporter, who had already owned a Wheeler and Wilson machine for some fifteen years, tells us that he received special permission to tour the factory, and that anyone who visits will require such permission, due to the existence of industrial spies. The superintendent told him, "There are machines in this establishment which are kept under constant watch. At noon it is the business of one of the men to keep guard over them, and see that no one, under any pretence, without special orders from me, makes it a study. You see, therefore, we have to be a little careful whom we admit." The author himself was not permitted to tour portions of the facility due to the confidential nature of product development.

"The works of this manufactory -- and it is but one of a host of Sewing-machine manufactories, two or three of which claim to do as large or a larger business -- cover in round numbers seven acres of ground. Their business employs in its various connections as mechanics, salesmen, and agents, from six to seven thousand men and women. If we estimate, as is usually done, four persons to each family represented, we have a population of nearly or quite thirty thousand, a good-sized inland city...supported directly by this industry. There is a postoffice in the establishment, and a very pleasant sight it was to see the men at noon gathering here for their letters and papers."

"The work is carried on in a manner which may not be unusual, but which was novel to us. All tools and materials are furnished at a certain price to subordinates, who are jobbers or contractors, and who furnish the finished article, or to speak more accurately, the article finished up to a certain point, at a definite sum per piece. The Company reserve the right to accept or reject work, and also the right to discharge any workman, though employed by a contractor. Thus they keep control of their great establishment and yet give to their employes a share in the profits, and an interest in its progress. Some of these contractors are men of considerable wealth. The result of this plan, and of a general rule to investigate very carefully any single complaints or isolated applications for higher wages or different positions, and to refuse to treat with the men as a class -- in other words, of regarding them as individuals, not as a crowd, and of granting justice to the application of any one, but nothing to the threats of the many -- is that the company have never suffered seriously from a strike."

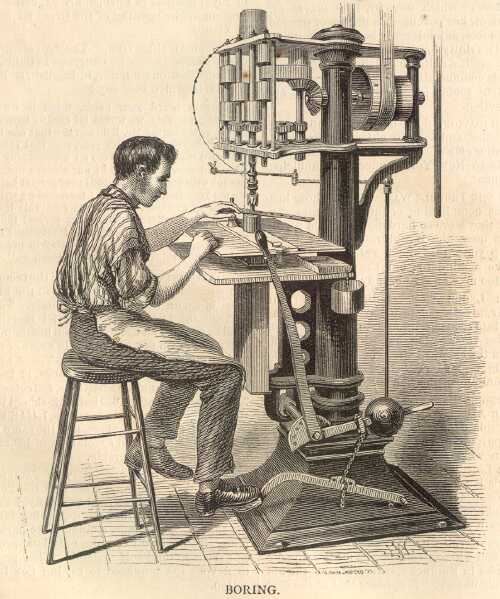

"We follow our conductor out of the office, through a short passage-way, thence through another great door, and are in the large machine-room. Whew! what a change from that absolute quiet to this ceaseless racket. It is a long room...and appears to our imagination quite a long as two ordinary city blocks -- full of machines drilling, planing, turning, cutting, polishing away with indefatigable and tireless energy...The room is composed of two halls of unequal length, at right angles to each other. We ask our conductor how many machines he has at work here. He does not know. We count in one row twenty-eight, and there are five or six rows...They [the machines] are for the most part, lathes and drills. Every conceivable and inconceivable kind of turning and boring is performed here."

"Mr. Whitney reproduces for us one of these machines, one of the simplest sort. The band running from the wheel in the background connects it with the 'power', i.e., with the great shaft which drives all the machinery. The complicated set of wheels above regulates the motion. The wire running from the top of the machine to a point just above the operator's hand, feeds it with oil from a reservoir above. Oil, oil, oil everywhere -- the whole room is soaked in oil. And yet, despite its superabundance, the iron and steel in certain of these manifold operations, smoke with the heat of the friction. This is the room where the bobbin and the hook, the centre and heart of the sewing-machine, are made, or rather finished."

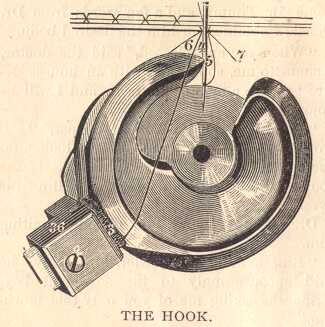

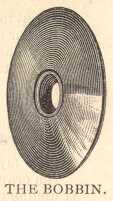

On the operation of the hook, bobbin, and needle, the reporter continues, "It must suffice to say in general terms, that the needle plays up and down above forming one thread of the stitch, while the hook catches it from below and locks it into the other thread, forming what is the peculiarity of the 'Wheeler and Wilson' -- the 'lock-stitch'...The work involved in the manufacture of the sewing-machine is apparent from the statement that the bobbin alone has to go through seven distinct machines before it is completed and ready for use, and that the glass plate in the presser-foot goes through from 18 to 25 distinct operations."

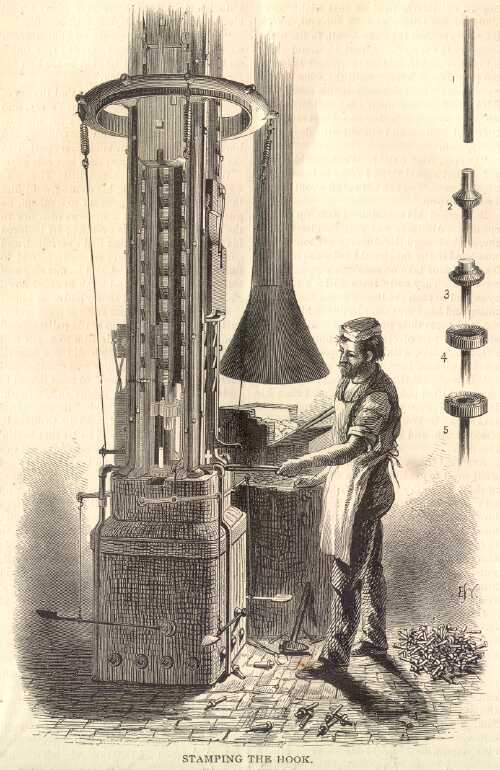

"[This] is perhaps better illustrated in an adjoining apartment, the furnace-room. Here we trace the first processes of the manufacture of the hook. A furnace and a stamping machine stand side by side. The stamping machine is operated on a principle somewhat analogous to that of a pile-driver. An immense weight is lifted up by machinery till it reaches the desired height; then falls with a clang on the rod. The machine is four-sided, and the rod, heated in the adjoining furnace goes from one side to the other till it has completed the circuit. The first blow converts the simple iron rod, No. 1, into No. 2, the second into No. 3, the third into No. 4, from the fourth it emerges No. 5; by this operation the hook (wheel and shaft) is made from one solid piece of metal -- an improvement on the old method. Thence it goes into the lathe-room to be turned into its final form as represented in the cut entitled 'the hook'."

"An even more striking illustration of the complicated operations required is afforded by the history of the needle which enters the needle-room a long coil of wire, and issues from it ready for the sewing-machine. In the course of this circuit it goes through ten distinct operations -- ten that we counted and noted in our memorandum; how many more that escaped our observation we have no means of judging."

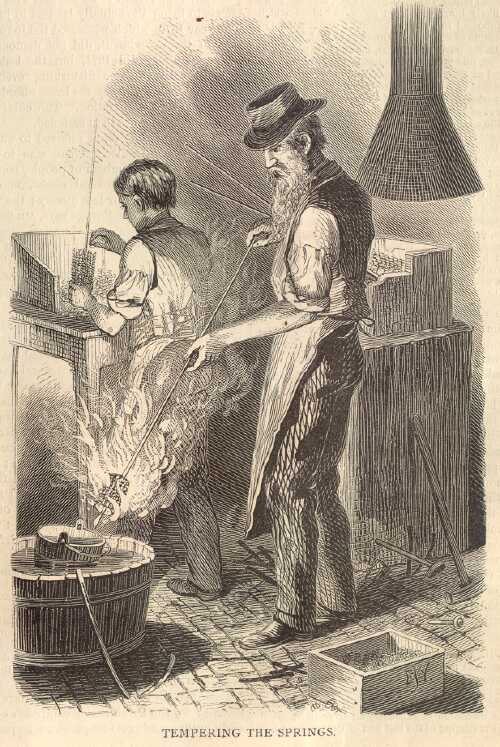

"The most picturesque operation in the whole factory is that of the tempering of the springs. The capacious and lofty hall with its smoked-begrimed walls, and dusty atmosphere, filled with stalwart workmen, their faces and brawny arms lighted with the glare from the many forges, and the banging and clanging of hammers large and small, all forming accessories to this one grand illumination from the burning oil, make it impossible to give the reader a just representation of it in the limits to which our pictorial efforts are confined. The springs, though a seemingly small part of the sewing-machine, perform a very important function. On their perfection largely depend the accuracy and smoothness of the workings of the whole. The tempering of these springs, therefore, is a task requiring very great care and accuracy in the workman. An assistant arranges a number of them on a sort of frame so that they present the appearance of a wicker-basket. The workman then heats them to an intense heat in his furnace, determining the heat by the color, and then plunges them into a pail of oil which is itself kept cool by being immersed in a large tub of water. The oil blazes up instantly, lighting the spot with a peculiar lurid glare, but goes out when the springs are withdrawn. The oil quickly burns off from them, the workman meanwhile revolving them slowly in the air as seen in the accompanying engraving. Everything in this operation depends upon his skill and judgment."

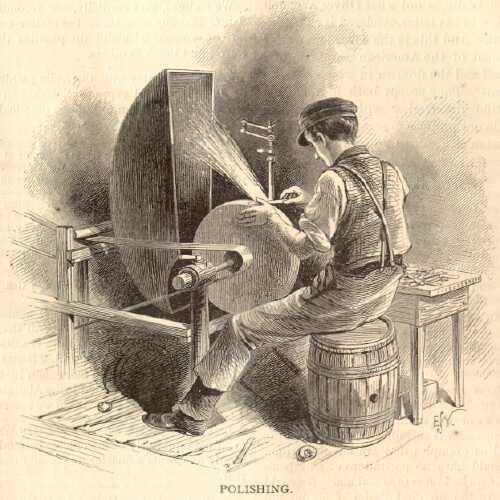

"There is the polishing-room, where the emery-wheels are revolving with incalculable speed, lighting up the face of the operator with a shower of sparks; there is the carpenter's shop where the cases for these machines, themselves of various forms and patterns, are in process of manufacture; there is the casting-room where the castings are made; there is the great engine-room which supplies all the 'power'; there is the finishing-room where the various parts of the machine, made by so many hands, are put together and adjusted; and the trying-room where a hundred or so of sewing-machines, in a row, are busily at work doing nothing, driven by steam in a profitless industry, the office of which is to see that they are really ready for the market."

The reporter ends the tour with a paragraph on the glory of sewing machines -- and a surprising comment on women's rights and labor-saving devices. "Get a good sewing-machine if you have not one already. We commend it as an alleviation of life's burdens. We commend because it takes drudgery from woman and gives it to machinery. We commend it because it saves the eyes, the nerves, the muscles, the head, the heart. We commend it because it accomplishes in one hour what the unaided hand takes a day to accomplish, and so leaves the mind time for self-improvement. The man who invented the sewing-machines, and the men who make them, are doing more for 'women's rights' than all the conventions which have been held since Eve claimed her independence..."