Sewing Machines at the London Exhibition of 1862

THE FIRST Great Exhibition of the Industry of all Nations in London in 1851 at the Crystal Palace came before the large scale commercial development of the sewing machine. There were a few machines there and they were all early prototypes.

Eleven years later the International Exhibition of 1862 sought to repeat the great success of the 1851

Exhibition. The exhibition site was in South Kensington on the site now occupied by the Natural History Museum

and the Science Museum. Exhibits were sought from all over the world and set out to show a wide variety of

arts and manufactures. In the event about 50 types of sewing machine were on show on over 20 stands.

The sewing machine industry had a slow start in Great Britain. Whereas the 1860 census in the USA estimated

the total number of sewing machines in use as more than 300,000 the estimated number in Great Britain was less

than 10,000. By 1860 companies like

Wheeler & Wilson

were producing over 800 machines per week but there were no large scale manufacturers in Great Britain. At the

time (1859), the

Practical Mechanic's Journal

summed up the reasons as follows:

"The first practical machines were introduced from America; and having been copied in this country, many inferior imitations of them, made as cheaply as they could be for the purpose of sale, were disposed of before the owners of the earlier patents had taken much notice of them. After a time however, some of the large American manufacturers sent over their own machines for sale, which, although much higher in price than those we have above referred to, commanded an extensive sale. These machines were also sold for some time without exciting the attention of the earlier patentees; but one of these parties ..... commenced proceedings against the users of the American machines, and up to the present time (1859) has succeeded in stamping them as infringements. .....The effect of this state of things at the present time is to impede very greatly the use of sewing machines in any shape, without really benefiting anyone. .. Law proceedings, which appeared interminable, would have been avoided."

The "parties" who carried on this litigation were Fisher & Gibbons and W F Thomas who had bought the Howe patent and registered it in his name in 1846. The Thomas patent, with its disclaimers, finally expired in 1860, just in time for new machines to be produced for the 1862 Exhibition.

The sewing machine was well represented in the Exhibition with displays from 18 British manufacturers or agents, six American manufacturers (all the big names) and manufacturers or agents from France, Belgium, Germany and Austro-Hungary. Articles on the machinery exhibited in 1862 were collated by Daniel Kinnear Clark, a noted steam engine engineer, in a book published after the Exhibition closed. Sewing machines warranted a complete chapter which provides a good survey of the machines available in Britain at that date. This article is an annotated review of the 1862 catalogue and D K Clark's book.

The British exhibitors (The numbers are the stand numbers in the exhibition gallery).

1560 Bradbury & Co, Rhodes Bank Foundry, Oldham

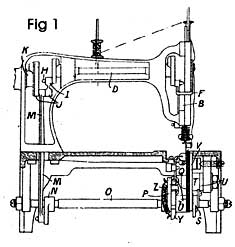

Bradbury had a display of 'manufacturing and domestic sewing machines and binding guides.' Notable was McCrossan's 'Empire' sewing machine patented (number 2340) by Joseph McCrossan on September 26 th 1860 for GJuengst. The machine [fig. 1] used eccentrics rather than cams to drive the needle and shuttle, and had an offset drive shaft to the needle bar (like the much later Wheeler & Wilson No 8 drive to the hook) to give a slow downstroke, pause and quick upstroke to the needle.

1566 William Carver, Ducie Street Mill, 5 Todd Street, Manchester

Carver's display was said to be the most productive in the Exhibition, producing over 20 pairs of trousers each day. The machines were said to be identical with the Thomas machine! Carver was probably a Thomas agent.

1583 Deane & Davies, 19 Blackfriars Street, Manchester

The entry states 'sewing machinesand other exhibits'. I have been unable to identify the sewing machine exhibits and suspect that Deane & Davies were agents for some other machine.

1596 Henry Ferrabee, 75 High Holborn, London

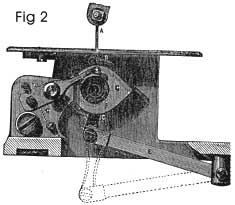

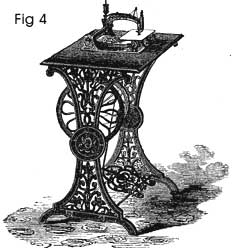

He exhibited the 'British' sewing machine which used the same lock-stitch forming mechanism as the American 'Elliptic' design [fig. 2]. It was mounted on a fancy treadle table at £10 [fig. 3 & 4]. Henry Ferrabee shared a London address with James Ferrabee & Co who had a works at Stroud, Gloucestershire. Ferrabee of Stroud was a well known tool maker and a manufacturer of early lawn mowers, so the sewing machine may have been made by him.

1612 W G Guinness & Co, 42 Cheapside, London

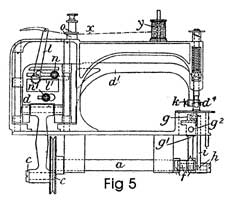

The William Stuart Guinness sewing machine was able to sew forwards and backwards and was covered by patent number 2143 of August 28 th 1861. The machine [fig. 5] was priced at £10 on a table and looks a fairly massive machine. It used three eccentrics rather than cams to drive the needle bar, shuttle and feed mechanism and all three were on top dead centre at the same time. Thus it formed the stitch equally well which ever way the shaft was rotated, only the direction of feed was changed. It was also claimed that, since the needle bar slide was at the back of the machine inside the over-arm, no oil dripped down the needle onto the work.

1637 William Keith, 11 Three Crowns Square, London

I have been unable to trace his 'Improved sewing machine'. Again, I suspect he was an agent.

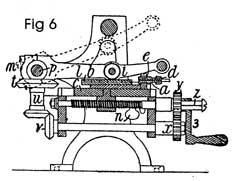

1647 Affifi Lely, Redditch

Amid many machines on this stand was a machine [fig. 6] for putting the groove in sewing machine needles. Lely had patented the machine (number 1974) on August 15 th 1860; an early patent for producing specialist sewing-machine needles in Redditch, the heart of the British needle industry.

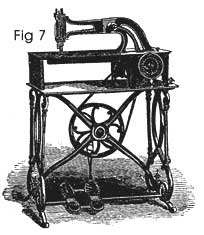

1653 Alexander Mackenzie, 32 Saint Enoch Square and 62 North Frederick Street, Glasgow

Mackenzie produced an ingenious free-arm machine [fig. 7] covered by his patent number 327 of February 7 th 1862. Such machines were called 'cylinder machines' and Mackenzie's version was arranged to sew both along a sleeve and round the cuff. The machine had a complete four-motion feed inside the free-arm, arranged to feed material either round or along the free-arm. Rotating the cylinder through 180 o changed the direction of feed through 90 o . A platform was provided to convert it into a flat bed machine.

1654 Luke McKernan, 98 Cheapside, London

McKernan had been the agent for the Howe Sewing Machine Co before he set up his own depot in 1861. Since the Howe SM Co had its own stand at the Exhibition and had fallen out with McKernan, I do not know whose sewing machines graced the McKernan stand.

1682 William Pearson & Co, Leeds Pearson displayed 'A cut-nail machine for headed nails; also various sewing machines'. Whose sewing machines they were is not known. Pearson had a foundry and supplied castings for others to make up.

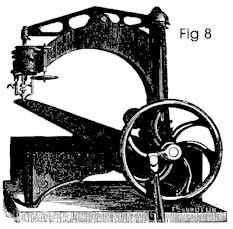

1675 Newton Wilson & Co, 144 High Holborn, London

The bulk of the Newton Wilson stand was taken up with a display of about 20 Grover & Baker machines, both two thread chain-stitch and lock-stitch, for whom they were the British agent. There was also a 'Boudoir' machine and a large Blake boot sewing machine [fig. 8]. The Blake boot sewing machine on the Newton Wilson stand used a chain stitch and was of a pattern claimed to make 150 pairs of boots per day for the US Army.

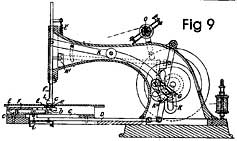

1698 S C Salisbury, Coventry

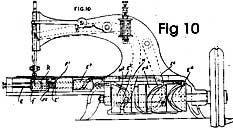

Silas Covell Salisbury exhibited a patent 'knot stitch sewing machine, simple, durable and cheap' [fig. 9]. This machine was a standard shuttle free-arm machine with the shuttle and carrier removed and replaced with a lower needle or looper to make a Grover & Baker stitch. There was also a free-arm machine with a very large shuttle taking a complete reel of thread [fig. 10]. The shuttle, or bobbin case, had a small hook to pick up the needle thread. The shuttle was then fed forward as it rotated, spreading the loop and passing the shuttle through it. The spiral cam to rotate the shuttle as it moved through the loop is seen at E 2 in figure 10.

The former machine is covered by his patent number 1045 of April 25 th 1861 and the latter by patent number 1059 of April 26 th 1861. Both patents were taken out jointly with James Starley and both machines clearly look like precursors to the Coventry Machinists Co. (Starley) 'Europa' free-arm machine.

1700 William Service, Mitcham, Surrey

I have been unable to locate details of his 'Double feed action sewing machine'. He was probably an agent. At this time 'double feed action' usually means a feed dog with strips on both sides of the needle rather than just one.

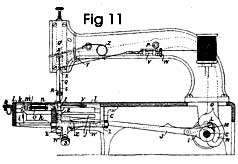

1708 R E Simpson and Co, Glasgow

I have been unable to identify Simpson's imported 'Patent American shuttle, single and double action sewing machines'. They would probably be derived from Grover & Baker designs. However, Simpson manufactured free-arm machines to a patent of John Thomas Jones (number 422 of February 15 th 1859) in which Simpson had an interest. This machine [fig. 11] is an industrial machine and is seen in the photograph of the Exhibition [fig. 12].

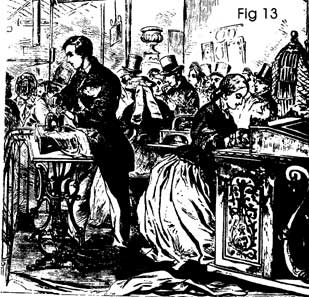

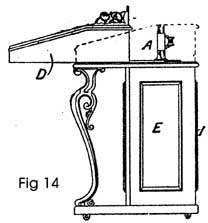

A woodcut of Simpson's stand [fig. 13] shows the Jones machines and a Davenport desk containing a machine which might be a 'Boudoir'. The Exhibition report mentions 'Their Davenport machine meets the requirements of the boudoir, being enclosed in a ladies' writing desk, which is thus made to serve the double purpose of a sewing machine case, and a useful article of furniture.' The desk has a sliding top and outline corresponding to the patent (number 2814 of November 9 th 1861) of R McNair of Glasgow [fig. 14].

1718 James Smith & Co, Crown Court, Crown Street, Finsbury, London

Smith displayed 'the "English" continuous motion shuttle sewing machine, simple, easy, durable and cheap'. He claimed that this was a machine invented, patented and manufactured in England. I have not yet traced it.

1726 W F Thomas, 1 Cheapside and 66 Newgate Street, London

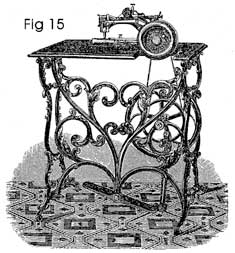

William Frederick Thomas was, of course, the man who had bought the Elias Howe patent in 1846. For 1862 he had a 'large assortment of different sized shuttle machines', all of his well known free-arm designs [fig. 15].

1733 The Victoria Sewing Machine Co, 97 Cheapside, London

The 'Victoria' sewing machine was a clone of the Wheeler & Wilson curved needle, rotary hook machine.

1739 Whight & Mann, Gipping Works, Ipswich. (London depot: 122 Holborn Hill)

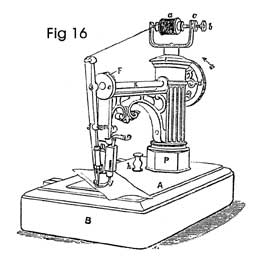

George Whight's exhibit was the 'Excelsior' two-thread chain-stitch machine [fig. 16]. This machine, the West & Wilson American machine, had been patented in England by Whight (number 89 of January 12 th 1861) for Theodore Stuart Washburn of America. Its chief peculiarity was the feed mechanism in which the needle moved the cloth along as the needle bar rocked on its crank pin.

1741 John Whitmee & Co, 70 Saint John's Street, Clerkenwell, London

The exhibit is described as 'Carley's patent elastic stitch sewing machine'. The name Carley does not appear in the English patent list up to that time. I have no other information on the exhibit.

We now come to the American exhibitors.

19a The Wheeler & Wilson Sewing Machine Co

Wheeler & Wilson had a large display of its curved needle, rotary hook machines [fig. 17]. The report eulogises: 'Messrs Wheeler & Wilson 's lock stitch machines attracted general notice for their beauty of finish, and for their easy, rapid, and silent manner of working. There is probably no lock stitch machine equal to Wheeler & Wilson 's for family use.'

Amongst the machines on its stand was a free-arm version [fig. 18]. I have never seen a woodcut of such a machine before, let alone a left handed one! Is such a machine known to have survived?

20 I M Singer and Co

Singer exhibited some 'good shuttle machines'. I do not know whether the 'turtle back' family of 1858 was exhibited. The review suggests the Singer Co only showed industrial machines. 'These machines are admirably adapted for manufacturing purposes and leather work, in which branches they are now extensively used. The wheel-feed is used in most Singer machines.'

21 The Wilcox & Gibbs Sewing Machine Co

The Wilcox & Gibbs chain stitch machine is the only single thread machine warranting praise from the editor. Having decried the single thread chain stitch on the grounds of unravelling he allows, of the W&G machine, that the seam 'if perfectly made ... will answer sufficiently well for ordinary family purposes. Indeed, in family sewing machines, the capability of unravelling a seam when desired is rather an advantage than otherwise, for work sometimes requires to be unpicked.'

21a The Howe Sewing Machine Co

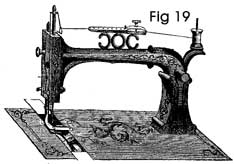

The (Amasa) Howe S M Co machines were described as 'unsurpassed in point of workmanship and finish.' Amasa Howe was awarded a medal for the machine and four medals for the quality of work produced by them. In addition to its flat bed machines [fig. 19] it exhibited the latest version of the cylinder machine for stitching leather. In this machine the awl-pointed needle pushed a loop of thread through the leather and was withdrawn before the shuttle picked up the loop. This was claimed to produce a more waterproof seam as a smaller hole was left in the leather.

22 C R Goodwin and Co

Goodwin was the Paris agent for the Grover & Baker Co. He had a display of their machines (as did Newton Wilson ) including industrials and leather stitchers. Goodwin also manufactured G&B machines under licence in Paris and held various patents himself for improvements to them. 'The varied display of well-executed embroidery produced on the Grover & Baker machine reflected great credit on the fair machinist, Mrs Rogers of California, who is said to be one of the cleverest experts in machine-sewing of the present day.'

23 H Wrigat and Co

This exhibit was a specialist machine for sewing tape and braid onto garments. I have no further details.

The remaining sewing machines on display came from continental Europe. The report starts by stating that 'the foreign sewing machines exhibited were, for the most part, copies of well known American machines.' The largest contingent was from France.

M. Callebaut from Paris showed 'several modifications of shuttle sewing machines . of the Singer type.' Callebaut was the Singer licencee in France (the only occasion on which the Singer Co granted a licence rather than manufacturing itself). Callebaut patented these modifications in France and Britain in his own name. Most of them apply to the Singer No. 2 machine and enabled it to have a reversible wheel feed for finishing seams, and to produce a 'herring-bone stitch' (zigzag) by moving the top feed presser foot from side to side. Another machine had twin needles on the same needle bar for making two lines of stitches on the top side and a zigzag on the underneath with a single shuttle thread.

Not content with all these variants, M Callebaut exhibited some glove making machines of fearsome complexity using detached lengths of thread!

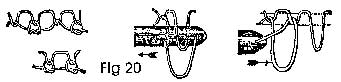

M de Celles , also from Paris, exhibited 'a curious lock stitch machine, of American origin, having the property of forming a perfect knot, like a weaver's knot, in the shuttle thread, at each stitch.' I can not find the source of the 'American origin' but such a machine was patented in Britain by Henry Fletcher in 1859. The stitch produced is shown in fig. 20. The shuttle was pointed at both ends and went through each loop twice in making each stitch. As the editor correctly added 'If the knot be not tied close into the material, it does more harm than good, by preventing the proper tightening of the stitch, as there is no slip in it once made.'

M le Blond of Paris 'exhibited some good specimens of workmanship'. They included machines which could produce lock stitch, Grover & Baker stitch or single thread chain stitch by fitting various accessories.

M le Roy of Brussels 'exhibited a machine for stitching button-holes, in company with a large assortment of other kinds of sewing machines.'

M J Warchalovsky from Vienna exhibited two machinesa shuttle machine and a single thread chain stitch machine. They were provided with 'duplicate sets of sewing instruments, to work simultaneously, and consequently to produce two seams at the same time.' The chain stitch machine used an oscillating hook of the form used in F N Parker's patent of 1859.

From Germany, M F Böcke of Berlin 'exhibited a large collection of sewing machines, copies of different American machines.' The other German stand was M J Schröder of Darmstadt who exhibited three machines of the Grover & Baker pattern, two double thread chain stitch and the third, a G&B lock stitch machine.

So finishes the review of the 50 or so machines. Apart from the American entries, not many survived long or became major producers of sewing machines. Only Bradbury of the British entries survived into the 20th century. There are lots of gaps in this review I would welcome information on any of them.