An Interview With Antique Sewing Machine Collector Harry Berzack

Harry Berzack (recent co-host of the Charlotte Convention) is a collector of 19th century and pre-World War II sewing machines. Unlike many collectors in this field, Harry's 500-piece collection is international in scope. Recently Collectors Weekly spoke with Harry about his collection of antique sewing machines, the history of sewing machines, their uses, and the four major manufacturers.

Berzack : I work for a sewing machine distribution company that was started by my late father. We mainly distribute industrial sewing machines. At a very early age, I became interested in sewing machines in a general sense, and I started collecting old machines mainly to see the technology and how it had developed. Then I immigrated to the States-I'm originally from South Africaand my new life caused about a 20-year hiatus in which I did very little with sewing machines, although the passion never left. About eight years ago, I started to have a little more time and I started to get back into it. Now it's grown to the point where today I have one of the largest and best collections in the States.

We have a museum at our business where I house my collection. We've taken a section of our premises here to create a full museum environment where the machines are on display.

I have almost 500 sewing machines in my collection. Initially, I brought some machines with me from South Africa and I picked up one or two here and there over the next few years, but most of the machines-probably 450-plus of themhave been acquired over the last eight years.

Collectors Weekly: Do you have sewing machines from all over the world?

Yes. That makes my collection a little different from most. Probably the best collection in the States is owned by a person named Carter Bays. Carter only collects American machines, and he has authored the standard book on antique American sewing machines. On the other hand, I have machines from America, Canada, England, France, Germany, Sweden, and Denmark, so my collection is more a worldwide but it also shows cross-influences.

I decided to collect from across the world intentionally. I just had a wide interest. There's a great museum in England, but most of the machines there are British. The German museums are a little more mixed. There are probably 10 very good museum collections around the world.

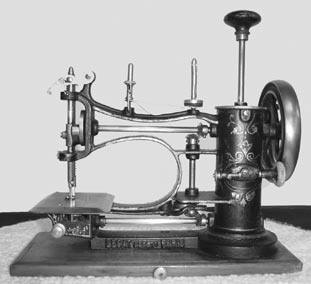

I'm more drawn to the ideas in the machines than the country that made them. I'm drawn to rarity. I'm drawn to condition. I'm drawn to mechanical design and how people thought up different features. Some machines survive to this day and some were inherently no good to start with. It's a passion of mine to see the way people thought, going back to the 1800s, and the sort of engineering they devised. They didn't have the machine tools we have today, and yet they did some incredible work.

The earliest machines probably come from the 1840s and they're very rare. Then you get into the 1850s, and the big names were Singer, Wheeler & Wilson, Grover & Baker, Howe-just a myriad. There were literally hundreds of people who made machines in different countries. Very few of the manufacturers have survived, and that in itself is part of the story. The small companies were gobbled up by Singer and others.

It was evolution. It was competition. It's the old story: Someone's making sewing machines and other people think they're making a lot of money, so they say, "Why shouldn't I?" At that time it was a comparatively easy industry to get into. Sometimes the ideas they had were not that good. Other times they ran into patent infringement problems and they were put out of business. Strangely enough, this was happening all over the world.

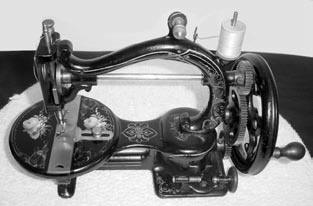

In America, there was a demand for household machines and a demand for commercial machines. The same sort of thing happened in Britain. With American machines, you had machines for home use, mainly with treadles because homes were bigger. In Europe, people didn't have as much room, so most of the machines were hand cranks, which made them more portable. A sewing machine typically has a wheel on the side that's used to position the needle and operate the machine. A hand crank is a handle that is attached to that wheel. Of course, in the commercial arena, it was all treadle and, later on, line shaft.

CW: So the hand cranks were used when there wasn't as much space?

It's certainly difficult to make a general rule. Some people just didn't want a treadle cluttering up the room. They wanted something they could push in a corner or put in the bottom of a cupboard and take out when they needed it. Other people by necessity didn't have the room to put in a treadle or a cabinet.

To a lot of people, the sewing machine became a status symbol, so a lot of the cabinets are extremely ornate. Today, it's very often that the more ornate the cabinet, the better the condition of the machine because they were show pieces. They weren't used. A machine that was really used a lot may sell for $5 and then, at the top of the market, you'd have the same machine encrusted with mother of pearl. By and large, those machines are in great condition today because no one wants to use them.

In America, the four majors were Singer, Howe, Wheeler & Wilson, and Grover & Baker. They basically held all the patents, and they were always suing their competitors for patent infringement. They formed a consortium and pooled all their patents and a royalty was paid to this consortium for every machine made, including by themselves. They had some formula where they divvied up the proceeds each year. They had no hesitation in closing down other companies on patent infringement, so a lot of people sought to do things a different way to overcome the patents. For example, there were machines where the needle, instead of coming from the top down, was linked to the bottom and came up through the plate of the machine like an upside-down machine.

CW: What were some of the earliest designs that were being manufactured?

It evolved very early into the form you have today - a base, an arm, the top coming across to hold the needle, and a drive from the underneath with either a bobbin or a shuttle. Those were all pretty early. There were circular-shaped machines, open latticework machines-difficult to explain without having pictures or really working with it.

Then there's another whole subset, and that's toy sewing machines. As the mother used to sew, the daughter used to have a little toy machine to make garments for her dolls. Those machines are mainly German by two big companies and a number of smaller companies. There were some British companies like Vulcan, too. It's a completely different interest, although I've got a small toy collection. It's more the premium toys, though, because those are the more interesting ones to me. I have one toy machine from France from around 1867. I think that's my earliest toy machine.

The real way for anyone to really get into this is to look at some of the collections where they'll be able to see machines that they otherwise would never see. For example, there's an American machine called the Manhattan, and there are only two known Manhattans that have survived. I have one and Carter Bays has the other. It was made by a New York company that called themselves Manhattan Sewing Machine Company. They made very few machines, probably less than 2,000, and then they disappeared.

CW: What are some of the other known rare machines?

There are a number of machines in Carter Bays' collection that are the only known examples, but you always have to be careful saying that because you never know when another one's going to come up. For example, I had a machine that was the only known example and now there are three. I have two and Carter has one. So there are machines out there and eventully you will find them. Everyone wants the rare machine. Two weeks ago, I drove 2,300 miles because I found a machine just outside Kansas City and the only other known example of that machine is in the Smithsonian. So now I've got the second known one, but until this one appeared, no one knew that it even existed.

To anyone who's getting serious in toy machines, a good introduction would be the two volumes by Glenda Thomas. For American machines there's Carter Bays' book, The Encyclopedia of Early American Sewing Machines. It has illustrations and a bit of background on the companies: what they made, who they were, and when they were in business. Then, if you get more interested, you should join ISMACS. They're the biggest sewing machine club by far.

©2009 http://www.collectorsweekly.com/ Originally published by Collectors' Weekly and reproduced with their permission.