History of the Moldacot Sewing Machine

This article was originally written for "The Moldacot Enigma", a supplement to ISMACS News. It has been edited to include further research.

Moldacot with 'star' insignia and open wheel, red tin alongside

Of all the mysteries surrounding early sewing machines and their makers, none is stranger than those involving that delightful miniature - the Moldacot.

A long period of intensive research both here and in Germany has answered most of the questions and revealed a twisted tale of boardroom intrigue and financial shenanigans that make today's headlines on insider trading look tame.

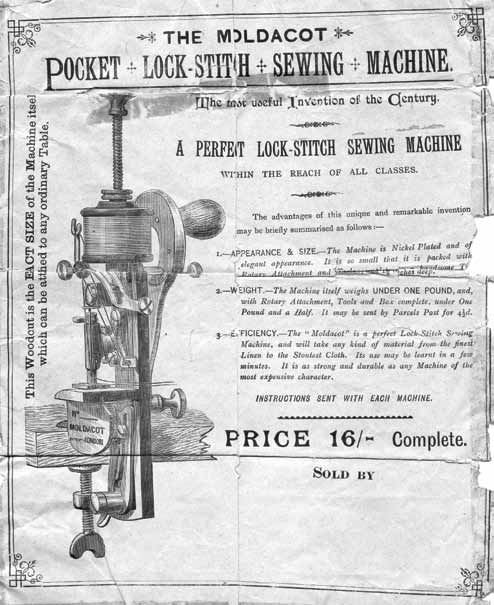

The Moldacot burst onto the British market in July 1886. When the trade first heard rumours of a lock-stitch machine which sold retail at half a guinea, 52½ p ($0.90c at today's exchange rate, but $2 then, as there were $4 to £1 sterling) most were skeptical. And when it was revealed that the model was of a size to fit easily in the hand, many dismissed it as a toy fit only for the novelty trade.

Rumours of the machine had started circulating in early 1886, so its announcement was no real surprise to agents, but it was the price that staggered them. This was no cheap, pressedout tin effort, but a finely-engineered piece of craftsmanship built from solid brass and heavily nickel-plated.

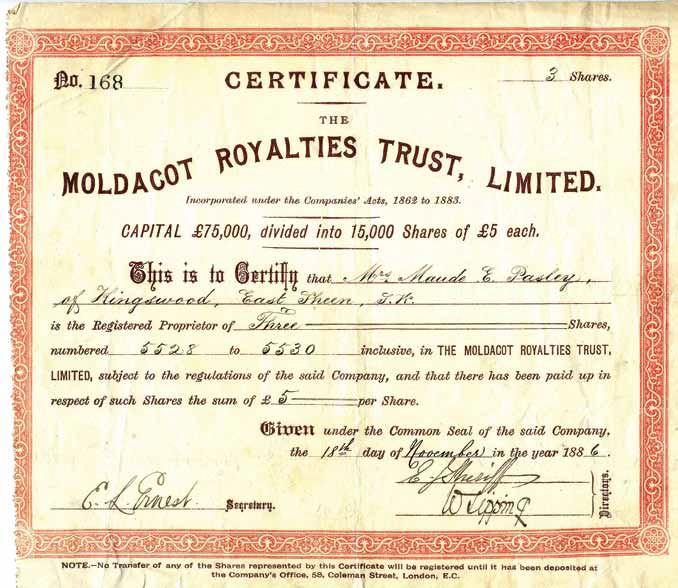

The Moldacot Pocket Sewing Machine Company was set up and the public invited to subscribe for the £75 000 offered in shares. That was an enormous amount of money for 1886, but within weeks the share offer was vastly oversubscribed. Unfortunately the share offer didn't state what the £75,000 would be used for, so we don't know at this date whether it was for manufacturing or simply for advertising and distribution. The prospectus aimed at prospective shareholders was a classic of its kind and was published as a full-page advertisement in the influential Financial News for 17 July 1886. It read, in part, as follows:

"The primary object of this company is to acquire, upon the terms and conditions hereinafter mentioned, the patent rights for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (Dated Dec 27, 1885, numbered 15 5l3), for the Moldacot Pocket Lock Stitch Sewing Machine, an invention which, in the opinion of those well-qualified to judge, is destined, on account of its extraordinary cheapness, efficiency and portability, to effect a most important revolution in the sewing-machine industry.

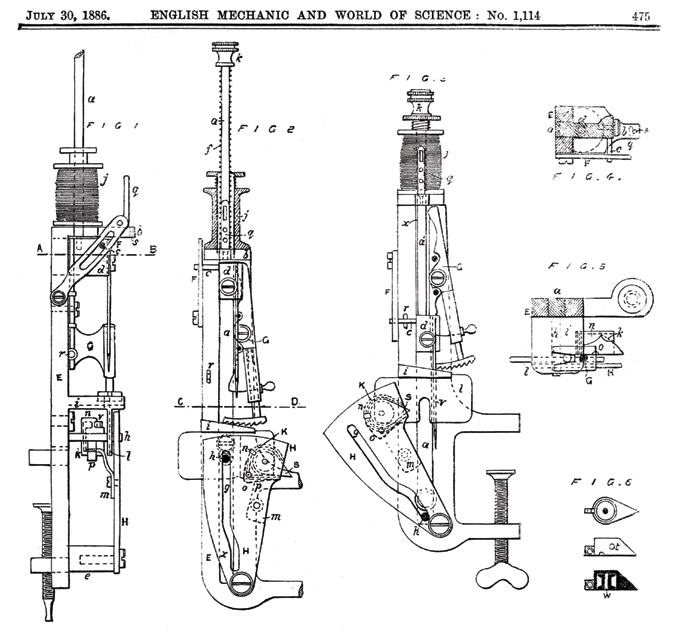

S. A. Rosenthal's patent of 1885 as featured in the 'English Mechanic and World of Science' for July 30th 1886

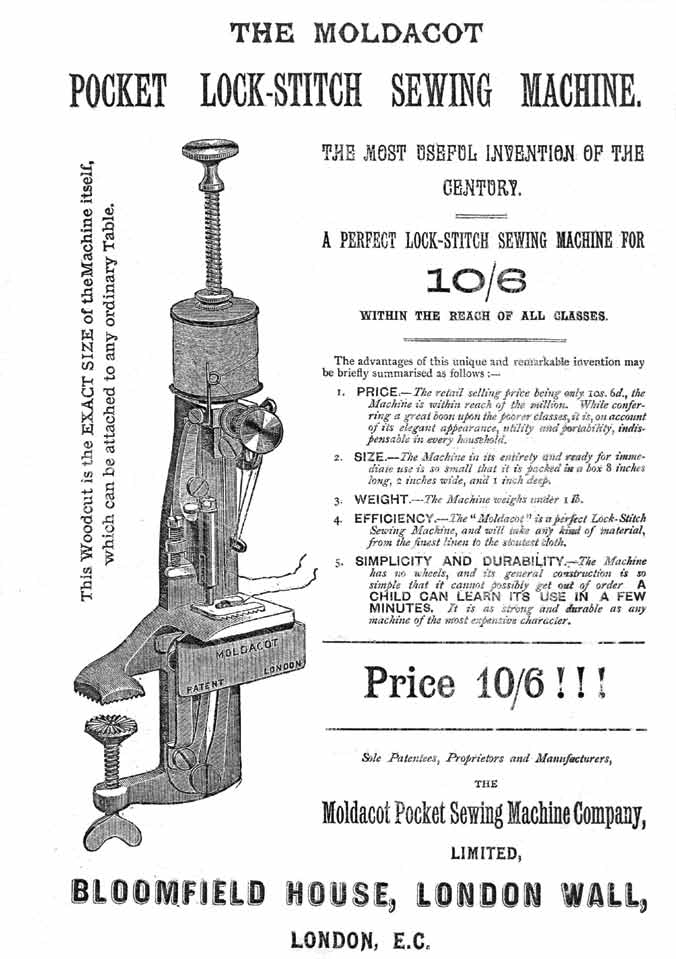

The advantages of this unique and remarkable invention may be briefly summarised as follows: 1. Price - the retail selling price being only l0s 6d, the machine is within the reach of the millions. While conferring a great boon upon the poorer classes, it is, on account of its elegant appearance, utility and portability, indispensable in every household.

2. Size - the machine, in its entirety and ready for immediate use, is so small that it is packed in a box eight-inches long, two-inches wide and one-inch deep.

3. Weight - the machine weighs under 1 lb. 4. Efficiency - the Moldacot is a perfect lockstitch sewing machine and will take any kind of material from the finest linen to the stoutest cloth. 5. Simplicity and Durability - the machine has no wheels, and its general construction is so simple that it cannot possibly get out of order. A child can learn to use it in a few minutes. It is as strong and durable as any machine of the most expensive character.

The history of the sewing machine is probably more striking than that of any trade speciality, and from no other source have larger fortunes been realised. Howe, the originator, notwithstanding, the almost-prohibitory prices at which, in his day, machines were sold, derived upward of £100,000 per annum from the invention.

Subsequent inventors were even more successful, and among those who have occupied prominent positions in this important branch of trade may be named Messrs. Wheeler & Wilson and Messrs. Singer & Company.

The former firm is reputed to have divided for many years an income of £200,000 per annum, while the proprietor of the Singer machines left at his decease nearly £3,000,000 sterling.

The attention of inventors and manufacturers has for years past been persistently directed to the introduction of such improvements in sewing machines as would materially lessen the cost of production, so as to popularise and bring them within the reaches of all classes.

The degree of success hitherto attained in these respects has been by no means remarkable, seeing the high prices at which lock-stitch sewing machines are retailed.

Moreover, as regards weight and bulk, no machine can compare with the Moldacot which, on account of these special characteristics, has been appropriately named a 'Pocket Sewing Machine'.

Notwithstanding the unprecedentedly low price at which the Moldacot machines can be retailed, the profit to the company, after allowing trade discounts to wholesale as well as to retail agents, will be considerable.

It is not proposed that the company shall undertake the manufacture of the machines, thus avoiding a large outlay of capital, and saving much expense in management.

Tenders have been received from eminent manufacturers for the supply of the machines at prices which will, in the opinion of the directors, leave a minimum profit of 2s 6d per machine."

It then went on to explain the profits that shareholders would make. It said it wouldn't be necessary to maintain expensive showrooms, etc. and that the machines would be sold through agents and shops of all kinds, including ironmongers, stationers, clockmakers and drapers. This way, more money would be available for dividends to the shareholders.

The first version advertised in the Journal of Domestic Appliances for September 1st 1886. This is the machine like No 18 which appears on the boxes

And what dividends these promised to be. The company stated that even before the share offer, 7500 agents were begging to be signed on and that sales in the first year were expected to be near the one million mark, and within three years five million were confidentially expected to be sold. Profits to shareholders from the initial one million machines would work out at over 150 per cent. The British patent rights were to be bought by the company for £35 000 plus a royalty of 6d per machine.

The British trade press was generally ecstatic about the potential of the company and money flooded in. The Pall Mall Gazette was typical.

"The invention seems to be thoroughly genuine, and the tiny machine is made on a sound and simple principle and of good material.

"Its first and greatest recommendation is that the company who are bringing the machine out promise nothing impossible from it, going even so far as to admit that it has some imperfections, which in the course of time may be improved, and that, for instance, the pocket machine will not be the ideal for sewing quilts and other very large or thick articles.

"Anyone calling at No.58 Coleman Street may see the new invention and convince himself that it sews material of average, and even more than average, thickness with a firm, equal lock-stitch.

"There is little doubt that the Moldacot pocket sewing machine will be a boon to the public, for its price as well as its size make it accessible to many families who are now unable to buy a sewing machine."

The one sour note came from the American press where one editor described the prospectus as an example of "what perfection has been brought to the art of counting chickens before they are hatched".

Perhaps this realist did the same mathematical calculation that I have just made. The nearest census figure (for 1861) gives the population of the UK at 24.5 million. If half of those were women and we allow a possible buying age range of 16 to 60 years, it's a potential sale of 7.5 million machines. In those Victorian days of large households it is not unreasonable to assume an average of three women per household and, as each home would only require one machine, that's a potential of 2.7 million sales. Therefore, by the company's own estimate, there would be no customers left without a machine within three years.

Moldacot share certificate for 3 shares sold to Mrs. Maude Pasley.

By October 1886 there were still no machines on the market. Shareholders were beginning to make noises and the American press was in full flood, calling the whole enterprise a "gigantic swindle". The far more cautious British trade papers tried hard not to take sides. Advertising interests may have coloured their decision, but eventually the swell of concern from shareholders and agents forced the Sewing Machine News into action.

Back-pedalling a little in stating surprise that anyone would have ever taken the Moldacot seriously, the editor sent a reporter to the company's new headquarters at London Wall to investigate progress. His report can certainly have done nothing to ease the fears of the shareholders. It read thus:

"If I could assist in unmasking any shady transaction, of whatever character, or in showing up anything not altogether over and above board, I deemed it nothing more than I ought to do. From members of the trade, and those in a position to judge, I heard on all hands adverse opinions of the Moldacot machine, and some very ugly statements were made to me.

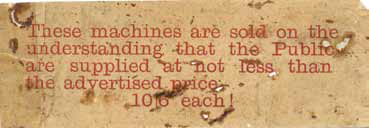

Packing slip enclosed with the machine for the retail agent.

I was asked why was it necessary to raise the gigantic capital the company has succeeded in doing to work a machine which they did not ever propose to manufacture themselves?

What purpose could the immense sum of money they have collected serve when other companies, working on infinitely-less capital, and making themselves, cannot find an outlet for all their funds?

Then I was told that the invention was that of a German savant named "Moldacot", and a brief interview with a German linguist revealed the fact that there was no such word as "Moldacot" in the German language. The trade scouted the idea of a practical lock-stitch machine for l0s 6d and simply laughed at the credulity of the public in subscribing their money to support such a thing.

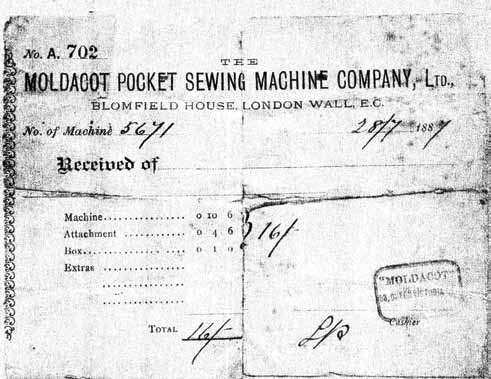

Receipt for the sale of Moldacot No. 5671 complete with hand gear and tin

So I determined to pay a visit to the offices of the company, who have just moved into a splendid building, known as Bloomfield House, London Wall. The company is located on the second floor, and has an immense range of rooms of large, handsome elevation. The directors are evidently liberal in their ideas of rent, and do not stick at trifles.

The rooms are most-stylishly finished and fitted in the latest style, and the shareholders will be pleased to hear that such luxuries as Turkey carpets, elegantly-finished mahogany secretaire desks, and other expensive articles are at hand for the use of the large, the very large, staff of clerks, assistants, office boys, managers, etc. I was admitted into the presence of the secretary, a Mr W. Irving.

The gentleman was reposing at an extra-large desk and graciously directed me to a room where a young lady was at work on a machine. This was what I had come to see, and was the veritable "Moldacot".

As far as I could ascertain, it was the only one in the possession of the company, but doubtless the fact that their capital was large enough to buy another dozen or so consoled the directors.

The machine, I learnt, was of an improved variety and different in many points to the original pattern, which, on my informant's own showing, was somewhat deficient. It was elegantly finished and highly plated, and were I a manufacturer of such things, I should be very sorry to have to turn it out at a price sufficient to allow the shareholders to get a profit on each.

The young lady did some plain simple work, and I noticed the peculiar bobbing motion of the plunger which works the thing. Its working entails a great deal of noise, and makes a most unpleasant clatter painful to the ear.

The cloth plate is an inch and a quarter square, and the idea of it doing such kinds of work as many sewing machines easily effect, is preposterous. The young person who worked the machine, evidently understood its peculiarities and treated the article very tenderly.

I was not allowed to work the machine and was told that the company did not allow any visitors to do so.

After I left I set myself thinking about the machine, and what it was capable of doing. It appears to me that the machine will never become popular as a practical machine with the general public.

One great question which must occur to anyone thinking over the Moldacot, is how will the company get the machine made to answer all practical purposes at a price good enough to pay the shareholders.

Again, if it is put extensively on the market, who will sell it, for the recognised agents in the sewing-machine trade do not favour it. At present there are no machines for sale and all I could gather was that some were expected in a month or so.

I leave the public and the trade to judge for themselves as to this matter and I hope you, Mr Editor, will have something to say on the subject next week."

In fact the original patent of 1885 was by a German, S. A. Rosenthal (Patent 15513 of December 17th) (Figure 1). By July 1886, two British inventors, A. D. Moll and J. C Cottam had patented improvements which give us the first version of the machine we see today. It is their names which are commemorated in the name Moldacot!

But that attack was mild compared with what was to come.

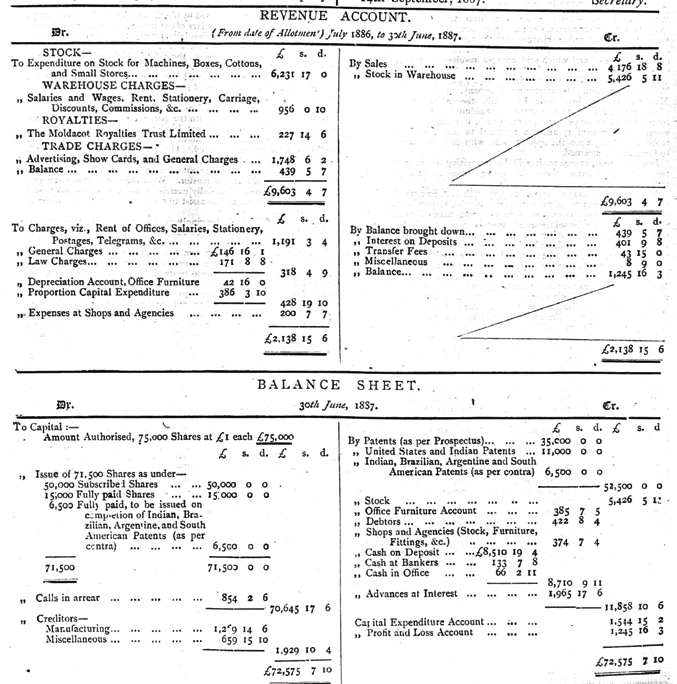

Balance sheet for the Moldacot Company as at 30th June 1887

Sticks and stones

Early in 1877 the American Sewing Machine News was speaking of the machine as "utterly worthless"; also branding the machine as a "fraud".

In fact the American Press – The Sewing Machine News, the Sewing Machine Advance and the Sewing Machine Times - was falling over itself to take credit for exposing the Moldacot mess.

This poem appeared in the Sewing Machine Times...

Who killed cock Robin?

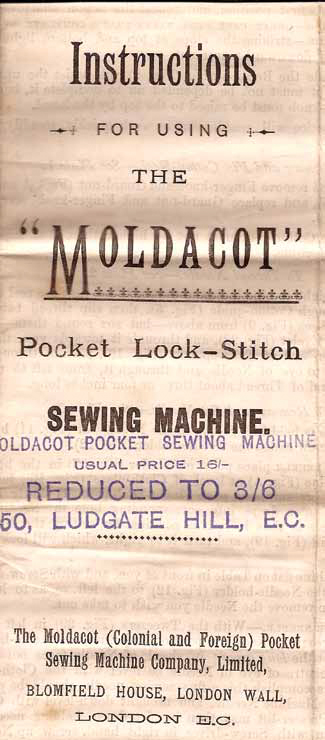

The instruction sheet for a machine sold off cheaply by the liquidator

(New version)

Who killed the Moldacot?

"I" said the News,

"I killed the cuss

With my blunderbuss.

I killed the Moldacot!"

Who dug his grave?

"I" said the Advance,

"With my pointed lance

I dug his grave!"

Who toiled his knell?

"We" said the Times

"With our merry chimes

We tolled his knell!"

The Sewing Machine Times, who christened the machine the "Moldy Cat", claimed it was that journal that first exposed the sad business. But all these funeral notices of mid-1887 were premature for the company was still trading and the more enlightened big-time manufacturers were even defending Moldacot, believing that a cheap machine would soon lead a customer to buy a "real" sewing machine.

The first significant confrontation between the high-living directors and the shareholders came in October 1887 at the first general meeting of the Moldacot Pocket Sewing Machine Company. The Chairman, Arnold Pye Smith, admitted that, as yet, the company hadn't achieved the anticipated success but talked about the "tide turning". He announced that the directors had purchased the patent rights for India, Brazil and the USA (perhaps he didn't read the American press).

I have tracked down the first annual report of the Moldacot Pocket Sewing Machine Company Ltd which was published in September 1887. The revenue account showed expenditure of £6231 for machines and boxes, £1748 for advertising and £956 for wages. Office rent came to £1191 and other small charges brought total outgoings to around £12 000.

Income was £4176 but it was claimed that £5426 worth of machines were stored ready for sale.

It's the balance sheet that tells the real story. Capital was £75 000, of which £52 000 had been spent in buying patent rights.

Smith blamed the poor performance in the UK on the manufacturers being late in delivering machines. He admitted that the two English manufacturers had found that they could not make the machine at the anticipated price. The directors took one manufacturer to court in an attempt to force him to make the machines but in the end had to re-negotiate the contract to allow the supplier to make a profit.

He revealed that up to 30 June 1887, 9109 machines had been sold (remember the one million estimated). Questioned, he revealed that around £17 000 had been paid for the foreign patent rights and when challenged he confirmed that, yes, the directors did have the power to spend money in that way.

One shareholder, a Rev M. Rynd, said that he felt he had been cheated. He had, he said, subscribed to the company on the basis of the prospectus to buy the British rights and provide working capital. To a groundswell of support from other shareholders, he offered £20 to start a fund to take the directors to court. Our reverend gentleman then proposed that a committee of shareholders should be formed with the power to investigate the company's books. This was immediately seconded and the committee formed.

The annual report that caused the row showed that of the £75 000 subscribed, £11 000 remained, which included sales of just over £4000. The report spoke of many unforeseen difficulties and, strangely in view of the statements in the prospectus, told of the opening of a number of sales depots throughout London and Manchester.

However, the committee never got to do its work. Just two months later the £11 000 was down to £3500 and the directors announced that there was nowhere to go other than to the bankruptcy courts. The liquidator found a ready market for the patents. They and other assets were to be sold to the Moldacot (Colonial & Foreign) Pocket Sewing Machine Company and again to the United Sewing Machine Company with more capital injected. The new company actually staggered on for another 10 months, but then the inevitable happened and a liquidator was appointed yet again to rake through the ashes.

The end came on the 24th October 1888 before Mr Justice Chitty who appointed Francis Cooper as liquidator of the United Sewing Machine Company Ltd, alias the Moldacot (Colonial & Foreign) Pocket Sewing Machine Company. It was stated at the hearing that the United Sewing Machine Company started with a capital of over £100 000, of this £78 000 had been spent, again buying patents.

On the 18th October 1877, the company had claimed that it had contracts to supply 240 000 machines and further prospects of sales of 175 000. Yet in the year following this and up to the time of the bankruptcy, not a single machine was sold.

At the liquidation hearing an interesting fact emerged. Far from a shortage of machines causing the company's downfall, the directors admitted having no less than 50,000 pocket machines stuck in warehouses with no customers and a similar number in a "foreign maker's" store.

It was also revealed that in a last-ditch attempt to save the company, the directors had bought the agency to sell a sewing machine called the American Empress. (This was probably a conventional Singer 'New Family' lookalike made by the Davis Company). This was yet another failure. The sample was taken around Britain to elicit orders, but when the machines arrived in Britain the shipping charges were a lot more than anticipated and the company did not have enough capital to pay the bills. At the date of the liquidation hearing the crates were still unopened in the docks.

Only the liquidation saved the company from litigation from the German manufacturer who had not been paid for his work.

The most telling indictment came from the English Sewing Machine Gazette commentary on the liquidation:

"We have good reason to think that the company, with such brilliant prospects, has not sold a single machine this year, and that the only business done by the office staff and directors was to arrange for the payment of wages, fees and expenses, drawing from the bank week after week the money originally put in and never adding a single farthing to the accounts.

They appear to have done no business whatever and, what is more, do not seem to have made any sincere attempt to do any. Sending out a traveller and, when he obtained orders not executing them, although 100 machines were in London ready for delivery, certainly cannot be called business. No, Canute-like, the directors appear to have calmly sat down and awaited the approach of the waves; they are on them at last, and we really cannot say that they deserve any better fate. Either they ought to have made an earnest attempt to do business, having ample capital at their command, or else have liquidated the concern months ago. They chose to do nothing, and now, we presume, the shareholders will get nothing."

It's possible to work out that the actual sales of the Moldacot sewing machine during the company's just over two-year history was something like 10 000 machines. The relatively large number that exist today come not from that total but from the 100 000 sold off by Francis Cooper, the official liquidator charged with the task of selling them off at any price he could get.

The last chapter of the Moldacot story was written in 1889 when one Emil Nusser, tennis racquet manufacturer, took former Moldacot company chairman Pye Smith to court in an attempt to get back the £500 he had invested in shares.

His case was that the original Moldacot prospectus contained statements which were not true. Faced with the prospect of hundreds of former Moldacot shareholders hounding him for the rest of his life, Pye Smith briefed a leading QC to defend him and eventually judgement was given in his favour. The judge ruled that it was impossible for Nusser to prove that he had bought shares on the basis of the prospectus rather than from newspaper advertisements for which Pye Smith was not directly responsible.

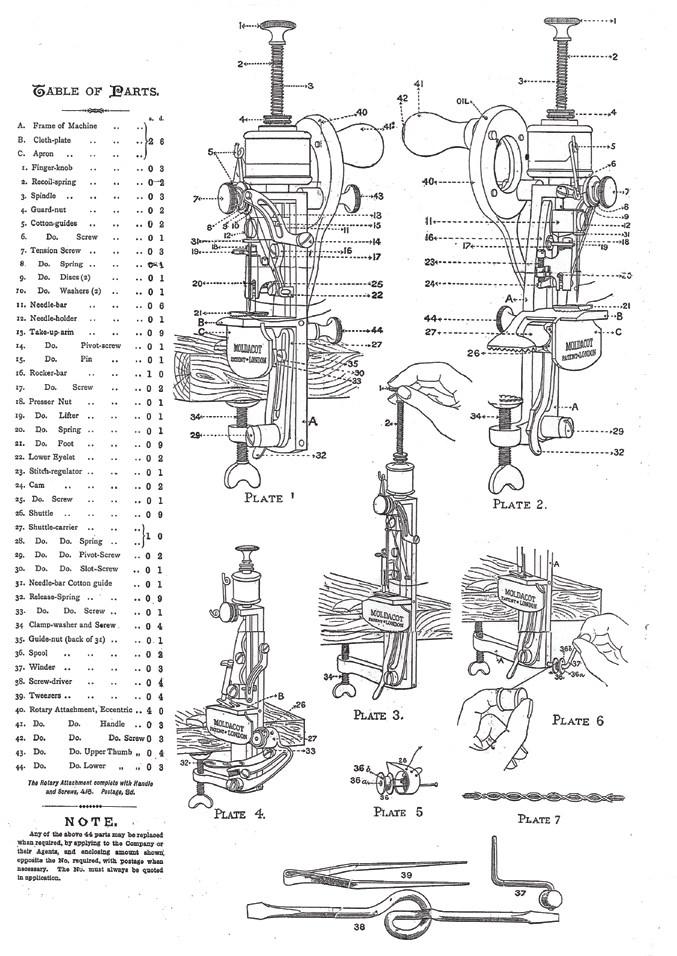

The diagram half of the single instruction sheet. The complete sheet is 22 in (560 mm) x 17 in (440 mm) and has to be folded at least five times to cram it into the tin

Was it a con?

American sewing-machine trade magazines seemed sure that the Moldacot company was a giant swindle right from the start. British papers were slower to catch on, but in the end were just as vociferous in their condemnation of how the shareholders were taken for a ride.

The bare facts are these:

1. Something approaching £100 000 was raised on the most fantastic of promises. 2. The directors blamed lack

of delivery for poor sales, but it was later revealed that tens of thousands of machines were sitting idle in

various warehouses.

3. The directors made very little attempts to push sales and lived high off the hog at prestigious London

offices.

4. Those same directors diverted money scheduled for advertising and distribution into buying patent rights

for the most unlikely countries.

But where was the swindle? It was not mentioned at the time. If there were any malpractices I would be looking for evidence of a backhander deal between the directors and the owner of the patent. Look at it this way. We have an inventor with a near-worthless patent. He had probably hawked it around all the established makers and received nothing but boardroom giggles for his pains. Yet he receives well over £50 000, more than two thirds of the share capital, up front before a machine is even manufactured. That £50 000 was a queen's ransom in 1886, enough to be split in quite a number of ways.

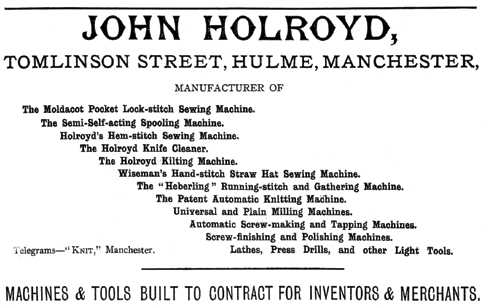

An advert. for John Holroyd showing that the Company was proud of their association with making the Moldacot

What of the unfortunate makers? Where were the Moldacots made? Production of the machine started seriously in the UK and Germany in late 1886. Initially, UK production was split equally between the Birmingham engineering company of Bown and a similar business of Holroyd in Manchester. Initial orders from each company were for 100 000 machines. This information appeared in a small paragraph in an 1887 American magazine and as a single source, would need verification before acceptance. There may also have been a third UK manufacturer.

That corroboration comes with a patent for 1886 made out in the names of Moldacot and Holroyd. Further confirmation for both companies has appeared since our 1990s research, in the addition of a Moldacot with the name Bown to the MS collection and an 1888 advertisement from Holroyd, listing the manufacture of the Moldacot amongst the company's activities.

We have not found out the name of the German company or companies that made those stamped 'made in Germany'.

There was even an attempt to sell to the Moldacot on the French market. It, also, was cloaked in deception. The company opened an office in Paris at the Rue Vieux Colombier but for some reason put up a shop sign saying "Home of American Inventions". As the only other products were German Naumann sewing machines and English cotton, it wasn't long before the equivalent of the Office of Fair Trading closed the shop.

Is it a toy?

Though tiny, the Moldacot is a cleverly designed and well-engineered machine and one of the smallest lock-stitch models ever made. It was always intended to be a carry-around portable, a miniature, but not a toy. The company even called itself the Moldacot Pocket Sewing Machine Company.

An American newspaper wrote: "To us at this distance this machine would seem to be but a toy, similar to many that have been produced in this country, but that it is not so considered in England is evidenced by the fact that a number of eminently-respectable gentlemen in London have organised the Moldacot Pocket Sewing Machine Company, with a capital of $375 000 (at the then exchange rate) to acquire the patent rights for the machine for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland."

As we have often stated in ISMACS News, the intentions of the manufacturer and/or marketing company determine whether the machine is to be considered for domestic or juvenile use.

Moldacot with closed wheel, made in Germany, with its blue tin

Epilogue

The American New York-based Sewing Machine News pulled no punches in its condemnation of the machine.

"When it comes to that part of the journalistic duty of the Sewing Machine News which consists in denouncing fraud in sewing mechanism the instant it rears its head, that duty is always done unhesitatingly, vigorously and completely.

"It will be remembered that as soon as the notorious 'Moldacot' pocket sewing machine made its appearance in Great Britain, with a great blare of trumpets and the heralding of a startling mechanical revolution, the Sewing Machine News was the first and only paper to expose and denounce it as utterly worthless and a fraud, and warned the general public against the machine, assuming that there would be no necessity whatever to warn the trade against such a transparent humbug.

"To our amazement the trade press in England actually gave the 'Moldacot' countenance instead of denouncing it. Now, after much delay, the European trade papers have come round to our way of thinking and, at last, the true character of the Moldacot has been slowly discovered by the British public.

"Thanks to our thorough exposure the Moldacot atrocity can have no repetition here. The patent has fallen dead in the Patent Office, and that is all we shall ever hear of the Moldacot machine. But a good many English and Scotch people were cheated of their money."