Alex's wife Yanawith one of the magnificents

Magnificent Moldacots

The Perfect Pocket Portable

Well were do we start with this superb mechanical marvel, patented in December 1885, the Moldacot burst onto our markets on July 17th 1886. Priced at 10/ 6 (about 50p or 75c) it took the sewing machine market by storm. Described by the Financial News in glowing terms "as the most useful invention of the century". Within weeks the share issue was vastly over subscribed and £100,000 poured in from investors hoping to make a killing with this little gem.

£100,000 was a vast sum in the Victorian era, when the average weekly wage was a few shillings. The advert read - "The Moldacot is a perfect lockstitch sewing machine that will take any kind of material from the finest linen to the stoutest cloth" (wow, was that an exaggeration). One of the reasons why this ingenious machine took so many people in was the fact that it was a very well engineered piece, "at last a machine well within the reach of the classes" the papers of the day stated.

We are surrounded with questions about the Moldacots. In the centre of our web are the almost invisible inventors A.D.Moll and J.C.Cottam. From their names we must assume that they were the beneficiaries of the scam? What was their connection with S.Rosenthal, the main inventor from Berlin? Recent developments at the Smithsonian have shown S. Rosenthal to be a woman named Sally. She was connected to a later Moldacot patent application. Although little else has turned up to date. Also the names of, C.J.Croft, F.Dowling, JJ.Robinson, and J.Holroyd. Wm.Bown and F.S.Sharpe are all connected with other various Moldacot patent applications. This makes things as clear as London pea soup. Yet another patent application appears by Moll and Cottam in July 1886 when they applied for improvements to the Moldacot, mainly for hand wheels that were later attached to the machines. However they were certainly not on the board of directors and no trace of them turned up in the liquidation hearings. They seem to fade away into history. Did they all run off together and live happily ever after in a suburban semi near Walthamstow?

The Moldacot offices were based at Bloomfield House London Wall and 58 Coleman Street London. The chairman Mr Arnold Pye Smith looked as if he just sat by with the company secretary, Mr W.Irving whilst the company fell apart around them. To begin with they blamed the inability to manufacture the machines as the cause of their demise but we later find that around as many as 60,000 may have been produced (it is a big may, considering how few have turned up). There were at least three main manufacturers and although the German Company has yet to come to light, The British companies were J.Holroyd of Tomlinson Street Manchester, and W.M.Bown of Brearley Street Birmingham.

Within two years the company had shot to the stars and collapsed into the fiery pits of liquidation, manufacturing only a fraction of the 5,000,000 machines that the chairman had promised. Over £50,000 of shareholders money had disappeared in such things as manufacturing costs and patent rights. Was this possibly a nice retirement for our two inventors, Moll and Cottam? At a cost of 8 shillings to manufacture (an unacceptably high amount seeing, as they were only selling for 10s 6d and only later at 16s or $1.25) that would have accounted for many thousands of the "lost" shareholders cash. However, no matter what was going on in the book-cooking department by 1888 the then called United Sewing Machine Company collapsed. The Surplus machines were auctioned off to try and pay some of the debts.

A few machines were supposedly sold to an Italian firm and renamed Bonita (though Bonita is Spanish for beautiful) probably as a novelty more than anything, these are amongst the most sought after models and as rare as hens teeth. I doubt if they were sold as working machines. Years later some more were discovered in a warehouse. The strangest story of all, and quite unlikely, is that a stock of Moldacots found stored in a building about to be demolished several decades later, were sold to an American entrepreneur. He then shipped them to the States aboard the ill-fated Titanic only to disappear in a watery grave. The New York based paper the Sewing World noted; "The machine will not be remembered as the magnificent, but more likely as the notorious Moldacot". The London Times chipped in renaming it "The Mouldy Cat".

The real reason for Moldacots demise was very simple, the machine did not sew well, and it was temperamental and full of design flaws. It was released onto the market before it was perfected. Perhaps the pressure from the shareholders was so intense they rushed forward with manufacture. On studying the mechanism a few simple improvements would work wonders, a take up spring to remove slack thread from the shuttle area, an adjustable shaft to allow individual timing for each machine, a stronger action on the foot to allow the work to feed better, bobbin case tension springs and so on. It is easy for a sewing machine engineer today to say this with a 120years of sewing machine mechanisms to fall back on. However, the fact remains that Moll, Cottam and Rosenthal seemed to stop at the final hurdle and never got it quite right.

The Bonita.

Previous pictures show several other variations from the Askeroff collection

Were they so pleased with the influx of money they became side tracked, did they believe it was finished? I doubt it; after all, if the machine were easily operated, there would have been public exhibitions and displays; the public were more than willing to invest in the company. Any one who tries to operate a Moldacot soon discovers the pitfalls; only with careful manipulation can you give the impression of successful sewing. At the company headquarters there were specially trained girls that knew just how to sew with the machine and could give a good impression of the machine. However, they would not allow anyone else to have a go. Were Moll and Cottam removed by greedy businessmen who only realised too late they were still needed? The truth is that we will probably never know.

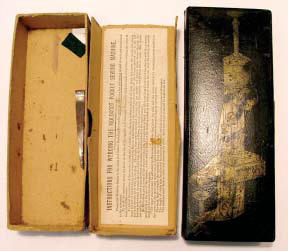

A selection of Moldacot boxes

What we do know is Moldacots turn up in an amazing variety of different boxes, green, red, blue, cardboard and my favourite, leather. The matchmakers Bryant & May, made the metal and cardboard boxes and still produce matches to this day. On the side of the tins were adverts like Horrockses finest cotton or Anchor Spliced Hose from Drapers, Morley & Gray of 36 Gutter Lane, London. Also the machines themselves differ quite considerably, plungers, hand wheels, closed and open (open being the more popular amongst collectors), many different stampings on the plates and other parts, crowns anchors, moons and crosses. The rarest of the Moldacots (but not the most sought after) did not have a hand wheel at all, although you have to be careful that someone has not just removed the assembly and it is a genuine one. All the different markings on the machines may lend some credence to the chairman's report stating the original difficulties they had in securing reliable manufacturers. Were they hoping that the manufactures would sort out the finetuning? Whatever the truth there is no doubt a lot more will come to light about the machine.

So here it is one of the most wanted sewing machines of all time, collected by toy and full sized sewing machine enthusiasts, treasured by other collectors as well for its superb design. With a little more effort it could have become a fine sewing machine carried by seamstresses and tailors in their pockets all over the world. Instead the Moldacot disappeared for over a century to reappear as a collectors item. The quality of construction of this little masterpiece is what makes it stand out so much. Scam or no scam in 1886 the Moldacot was greeted by an excited Victorian public as the perfect pocket portable.