We are grateful to John Brown who spotted sewing machine inventor Charles Kyte's former house for sale in a local newspaper. It reminded us that the mystery surrounding his '1842' sewing machine is still unresolved. History paints Kyte as a bit of a charlatan but it's still possible that his machine was as early as some believe but, as it has no shuttle, we still can't be sure if it sews.

Many years ago, as part of an ISMACS UK Convention, Graham Forsdyke examined all the available evidence in a lecture at the Science Museum (ISMACS News #44), which we present here for the benefit of new readers...

For the benefit of Mister Kyte

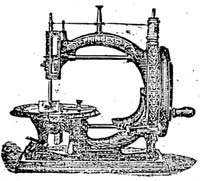

Much of what follows has been gleaned from the archives of the Science Museum which is to be congratulated on preserving the correspondence This sewing machine (above), which may or may not be the first practical machine ever produced, was in a parcel of old iron discovered in an old shop in Birmingham by surgeon Lawrence Tait. He firmly believed what he had discovered dated back to 1842 and was the work of a local character known as 'schemer' Kyte.

Just before Christmas 1892, he sent the bundle of artifacts to the Department of Science and Art at the V&A Museum, asking the curators if they would be interested in what he had discovered.

From the description noted by the clerk on the inventory list, it would seem that no-one in Exhibition Road was likely to get over excited.

His list read like this: 1 clockmaker's lathe 1 screw-punching machine 4 drills 2 hammers (broken) 1 drill brace 1 pair of dividers (all old and worn)

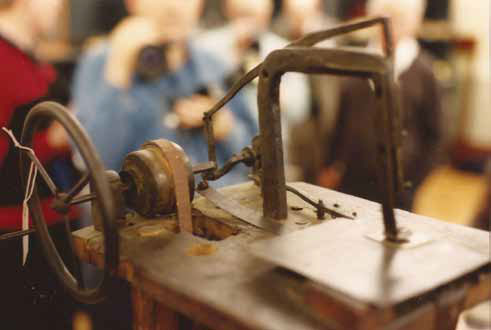

There was also a "rough, home-made lathe" used in the construction of the final item which was recorded as: "One old sewing machine supposed to have been made by Charles Kyte". The collection was offered to the museum on loan.

The museum obviously then wrote to Tait at 7, The Crescent, Birmingham, for he replied in March 1893 to say that he understood from one of the museum's staff, a Mr Sewell, that the authorities were awaiting a special report on the machine from their expert who had been ill.

Close-up of the Kyte sewing head and small wrought-iron flywheel.

Now, this expert, had he recovered enough to have viewed the machine, would surely have been able to accurately place it in the history of the sewing machine.

But the expert was none other than Newton Wilson who was ravaged by ill health from late 1893 until his death in May 1894. There is evidence from other sources that he did not leave his home during this period, so it is safe to say that the machine was never examined.

Newton Wilson, a pioneer British manufacturer, was the accepted authority on the industry's history and was midway through writing the most detailed and well researched account of the early days of the sewing machine when he died.

Shortly after Newton Wilson's death, Lawrence Tait wrote again to the museum saying that he now wished to sell the machine. He was obviously not looking to retire on the proceeds for he told the museum that it could name its own price, although he added that it would be nice if he could get his money back. Unfortunately he doesn't vouchsafe just how much he had paid out.

As a post-script he added that he had now found the shuttle which the museum could also have after the deal was done.

His letter rattled around the Department of Science and Art being considered by the Director and three other officials - I'm sure things are a lot more streamlined now!

Unfortunately all four gave the thumbs down to Tait's proposal.

One of them, W. Last, thought it best to thank Mr Tait but point out that "the department does not feel justified in recommending to my lords the purchase - owing to the evidence of it being little more than a copy of an existing machine"… "It's value in the history of the present sewing machine is very questionable".

Last also suggested that as a simple curiosity it could not be purchased but it would be welcome as a donation, and Mr Tait's name would go on the label.

Eventually the other directors agreed and Tait was told the bad news, but just what evidence there was to suggest that the machine was a copy was not revealed.

The mysterious Kyte machine. The truth of it will probably never be known. but this is the model that I would have grabbed if the fire alarms had rung.

Undaunted, Tait - whose letterhead revealed that he saw patients every weekday except Saturday, from 2 pm - replied suggesting that what the museum said might well be true but pointing out that some time earlier, experts had declared the machine unique.

He further stated that had the museum not delayed matters, he might well have been able to dispose of the machine earlier. Nevertheless, he said that the museum should retain the machine on loan until he was able to find a keen buyer.

Again the letter went the rounds with Last suggesting to the director that Tait be told that the machine could remain on loan for 'an indefinite period'. The director agreed and Last was to write to Tait.

Tait was still sure that the machine he'd found was historically important and approached the trade magazine, The Journal of Domestic Appliances, who wrote of his find.

The Journal also sent Tait's correspondence to the fast-fading Newton Wilson who failed to recognise the machine from the description. Whether this means that he failed to recognise it as a copy of another's work, or simply to report that he did not know of it, is unclear.

There was a promise in The Journal to go "deeply into the matter of the Kyte machine" in a future issue, but that period is missing from my archives and the only known copies of the magazine were sold off by the Patent Office to clear shelf space in the 1950s.

There was some talk of Tait lending the machine for an exhibition at the Crystal Palace in 1893 but records do not indicate whether this occurred.

The trail goes completely cold. No more is heard from Tait, nor his heirs and it was not until 1937 that the Science Museum delved into the Kyte file once more.

In October of that year, the Museum received a letter from a Mr Rushen drawing attention to an enclosed reference to Kyte and adding that "the correspondent, a Mr Barratt, is possibly the only person living who knew Kyte".

Unfortunately, in the intervening half century, the enclosure has gone missing so we can only wonder who Barratt was.

The museum replied to Mr Rushen that "it is believed that the machine is the work of Kyte but there is no certainty of this". The letter ended prophetically - "it is probably now impossible to obtain any confirmation".

Fifty seven years after that letter I doubt if there is the slightest chance of verifying the truth of Tait's belief. Tait himself probably explored just about every avenue in the 1890s and I'm sure that the museum staff did its best to get to the bottom of the mystery.

The museum never, to my knowledge, obtained the shuttle and the needle form is unknown.: If only Newton Wilson had been able to see the machine we might now know more, although he was a notorious jingoist and would have leapt at the chance of further debunking Howe's spurious claim to be the inventor of the sewing machine. Newton Wilson, do not forget, had suffered greatly at the hands of Howe's lawyers. And, perhaps, his opinion would have been coloured by patriotism.

So we shall probably never know the truth. It's not often that the serious researcher comes up against a really solid brick wall but this could be it. I've tried to locate Tail's descendants in Birmingham but to no avail and the British Medical Association and the Royal College of Surgeons lists no-one as Tail's successor.

I'd rather like to think that this was the first sewing machine and I'm glad that the Museum didn't let it slip away. But wouldn't it be nice if we had the shuttle?

One day when I've got a little time and with the museum's permission, of course, I'd like to make a shuttle and needle - bearing in mind the equipment Kyte had it shouldn't be too difficult today – and see if the machine could be made to work.

There's one other small mystery: just where does the date 1842 come from?

Was it as a result of some paperwork that came with the machine? Or was it, cynic that I am, a convenient guess just pre-dating Howe by the necessary couple of years?

Have a good look and make your own guess - it will be as good as mine and, of course, remember, that only "schemer" Tait really knew the truth.