A History of Innovation and Partnership

The King Sewing Machine Company, though perhaps not as universally recognized as some of its contemporaries, played a significant role in the American sewing machine industry during the early 20th century. Its history is marked by ambitious beginnings, a pivotal partnership with Sears, Roebuck & Co., and an eventual transition into other manufacturing sectors, reflecting the dynamic nature of American industry. The company's story provides valuable insights into the manufacturing landscape of the time, characterized by innovation, competition, and strategic alliances.

The Genesis of King Sewing Machine Company (1906–1908)

The origins of the King Sewing Machine Company can be traced back to the incorporation of the W.G. King Company in Buffalo, New York, in the fall of 1906. This new venture was capitalized with $100,000, and its initial directors included W. Grant King, a mechanical engineer with prior experience as a manufacturing executive, alongside Charles F. Kilhoffer and William L. Marcy. The convergence of engineering and business expertise in the company's leadership suggested a strong foundation for its future endeavors. King's background in mechanical engineering and manufacturing would prove crucial in establishing efficient production processes and ensuring product quality.

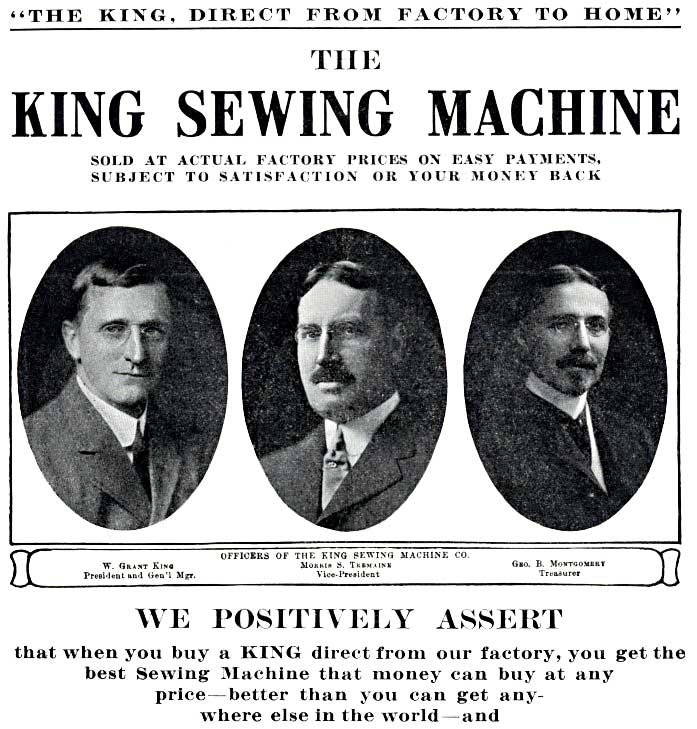

Officers of the King Sewing Machine Company

Key executives who led the company during its early growth period, including Morris S. Tremaine as president and W. Grant King as vice president and general manager.

By February 1908, the company underwent a name change, officially becoming the King Sewing Machine Company, with W. Grant King listed as president. This rebranding coincided with a period of significant expansion. By June of the same year, the company had increased its capital stock to $250,000, demonstrating a growing confidence in its prospects. This financial boost enabled the acquisition of numerous sewing machine patents, signaling an intent to manufacture a diverse range of models. This strategic move to leverage existing patented technology likely accelerated their entry into the market and broadened their potential product offerings.

The company quickly established its operational infrastructure. A factory was set up at 254 Court Street in Buffalo, and a retail store was opened at 630 Main Street to showcase their sewing machines directly to the public. To further reach potential customers, King Sewing Machine Company produced an elaborate catalog in 1908, featuring detailed images and instructions for their machines. This early focus on direct marketing and a comprehensive catalog indicated a strategy to connect directly with consumers and potentially offer competitive pricing by eliminating intermediaries.

Key individuals played pivotal roles in the company's early development. While Morris S. Tremaine held the position of president, W. Grant King served as vice president and general manager, actively overseeing the operations. Notably, Frederick Miller, a mechanical engineer with a decade of experience in designing automatic manufacturing machinery for a prominent sewing machine company, joined King as a director. Tremaine credited Miller with the initial idea for entering the sewing machine business, highlighting Miller's significant influence. Known as "Automatic Miller" for his expertise in machine building, he was instrumental in designing and building the specialized machinery and gauges required for producing precisely machined, interchangeable parts. This meticulous approach to manufacturing, with quality control measures allowing for variations of less than a thousandth of an inch, underscored the company's commitment to high standards from its inception.

Manufacturing Operations and Models Produced

The King Sewing Machine Company primarily focused on manufacturing vibrating shuttle machines, which were the prevalent type in the industry at the time. While adhering to this established technology, the company aimed to incorporate its own detailed improvements, though these were not always explicitly specified in historical records. Their initial machines were priced at $33 and were sold directly from the factory, through magazine advertisements, mail order, and their company store. Selling directly to households formed a cornerstone of the company's initial strategy.

Over time, King expanded its product line to include both vibrating shuttle (VS) and rotary sewing machines. Insights from vintage sewing machine communities help piece together the variety of models King produced and marketed under its own name or through partnerships.

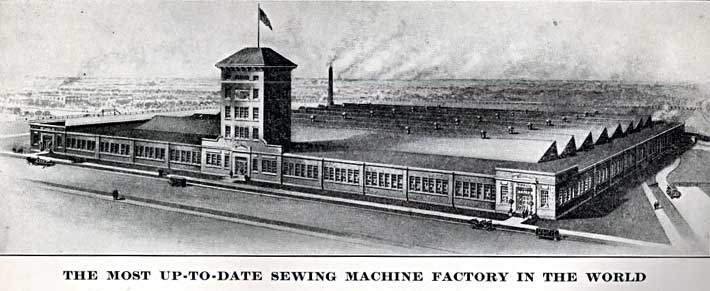

King Sewing Machine Factory Complex

The expansive factory built on Rano Street in North Buffalo after Sears' 1909 investment, featuring all-electric facilities designed to employ 500-600 workers.

Table of Known King Sewing Machine Models

| Model Name | Machine Type | Likely Production Dates | Associated Brands/Retailers | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| King Model | Vibrating Shuttle | 1908–1912 | King (Direct Sales) | Clone of Singer 27; early variants featured a 6-spoke handwheel with internal belt, later versions had a 3-spoke handwheel, external belt, and automatic tension release. |

| Franklin | Vibrating Shuttle | 1911–1919 (approx.) | Sears, Roebuck & Co. | Resembled King's "New Model A," some with scarab decals and 3-spoke handwheel. |

| Minnesota "New Model" A | Vibrating Shuttle | 1912–1919 (approx.) | Sears, Roebuck & Co. | Spool pin centered on the arm; later models had extended stitch length levers. |

| Domestic Vibrator | Vibrating Shuttle | 1915 onwards | Domestic | Featured a shuttle ejection mechanism. |

| Minnesota H | Vibrating Shuttle | Unknown | Sears, Roebuck & Co. | Included a leaf spring tension system. |

| Lessing | Vibrating Shuttle | Unknown | King (Direct Sales) | Leaf tension design. |

| New Willard | Vibrating Shuttle | 1915 onwards | King (Direct Sales) | Treadle and electric versions with varied decals; some later models had motors from Domestic and White. |

| Bison | Vibrating Shuttle | Unknown | Unknown (Sold in Buffalo) | Decorated with Singer-style Sphinx decals. |

| Prince | Vibrating Shuttle | Unknown | Unknown | — |

| Minnesota X | Vibrating Shuttle | 1912 (Sears Catalog) | Sears, Roebuck & Co. | Distinct take-up lever design. |

| Elmore | Vibrating Shuttle | Unknown | Sears, Roebuck & Co. | Shared traits with Minnesota K and King-made models. |

| Minnesota K | Vibrating Shuttle | Unknown | Sears, Roebuck & Co. | Leaf tension with compact stitch-length lever on the bed. |

| Domestic Rotary | Rotary | 1915 onwards | Domestic | Modeled after earlier Domestic Rotary types. |

| Domestic Hi-Speed 69 | Rotary (Electric) | 1919 onwards | Domestic | Electric version derived from Domestic Rotary. |

| King VS | Vibrating Shuttle | Until at least 1919 | King | — |

| King Rotary | Rotary | Until at least 1919 | King | Scarce model; final patent dated 1904, similar to Domestic Rotary Type 2. |

The first model released, often referred to simply as the "King Model," closely mirrored the widely used Singer 27, with the key difference being the absence of Singer's trademark badge. It was offered in several distinct variations: an early version with a flowing 6-spoke handwheel and a drive belt routed inside, a later version with a flatter 3-spoke handwheel and external belt, and a version that added automatic tension release functionality. Other evolutions included different methods of adjusting stitch length and variations in where serial numbers were placed.

Sears Roebuck Catalog Featuring King Machines

King-manufactured machines were prominently featured in Sears catalogs under the Franklin and Minnesota brands, reaching a nationwide customer base.

A significant development was the partnership with Sears, Roebuck & Co., which began around 1910. By 1911, King was producing machines for Sears under the "Franklin" brand. The first Franklin model closely resembled the initial King model, identified as the "New Model A" version. Sears catalogs from around 1912 also featured the "Minnesota" model, specifically the "New Model A," which was likely also manufactured by King. This model differed from the standard King model by having the spool pin located in the middle of the arm. Later versions of the Minnesota A included a long stitch length lever. Other vibrating shuttle machines produced for Sears included the Minnesota H, which featured a leaf-style tension system, and the Minnesota X, noted for its distinctive take-up lever. The Elmore and Minnesota K models, also sold by Sears, exhibited similarities to both King and Davis machines, suggesting potential design influences or shared manufacturing elements.

King's factory also built machines for the Domestic brand after 1915, including the Domestic Vibrator, which featured a shuttle ejection mechanism, and rotary types like the Domestic Rotary and the electric Domestic Hi-Speed 69. This indicates a deeper relationship with Domestic than may initially be apparent. Additionally, King continued to market its own "King VS" and "King Rotary" models through at least 1919. The New Willard was another King-branded machine, sold in treadle and electric versions, some equipped with motors labeled "Domestic" or "White." Other less common King-made machines included the Lessing, Bison, and Prince, each with specific design features or cosmetic differences.

Timeline of Operations and Geographical Presence

The King Sewing Machine Company's operational timeline spanned a significant period of industrial growth and transformation in the United States. The company's initial phase, from its founding in 1906 to around 1909, was characterized by establishing its manufacturing base and initiating direct sales. The first factory was located on Court Street near Wilkerson Street in Buffalo.

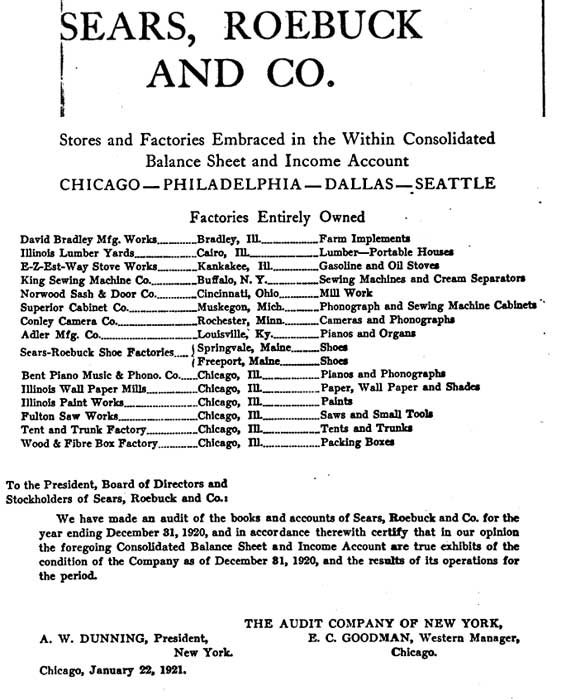

A pivotal moment arrived in late 1909 when Sears, Roebuck & Co. made a substantial capital investment of $150,000 in King, effectively doubling the company's capital. This influx of funds enabled King to undertake a significant expansion of its manufacturing capabilities. In 1909 and 1910, a large new factory complex was constructed on an 8-acre site on Rano Street in North Buffalo, on land leased from Walter H. Schoellkopf. The location's proximity to the Lackawanna Belt Line provided crucial logistical advantages for transporting materials and finished products. This new, all-electric factory was expected to employ 500 to 600 workers, a substantial increase from the approximately 100 employed at the older Court Street facility. The partnership with Sears also included a contract for Sears to take the entire output of the King factory, to be sold under Sears' own brand names like Franklin and Minnesota. This exclusive arrangement secured a major market for King's production. Further expansion occurred in 1912 with the addition of four more buildings to the Rano Street complex, utilizing 500 tons of steel, indicating the continued success of the Sears partnership and the increasing demand for King-manufactured machines.

The year 1924 marked a significant turning point for the King Sewing Machine Company. In February of that year, it was announced that the White Sewing Machine Company of Cleveland had acquired the rights and some property related to the manufacture of King sewing machines. This acquisition also included the Domestic Sewing Machine Company, leading to the formation of the White Sewing Machine Corporation. The sewing machine manufacturing equipment from the King plant in Buffalo was subsequently moved to White's facilities in Cleveland by April 1924. At the time of the acquisition, sewing machine production constituted about one-third of the King plant's output, with the remaining capacity dedicated to manufacturing automotive parts, cream separators, and radio components. Following the acquisition, the Rano Street complex in Buffalo was renamed King Quality Products in 1924 and transitioned to manufacturing radios for Sears under the "Silvertone" brand. The company underwent several further name changes in the following years, becoming King-Hinners Radio in 1926, King-Buffalo in 1927, and King Manufacturing Company between 1927 and 1930. In October 1930, Sears sold its interest in the company to the Colonial Radio Company, which relocated its operations from Rochester and Long Island City to the Rano Street complex in Buffalo. Colonial Radio Company became a primary supplier of radios for Sears throughout the 1930s.

The former King factory on Rano Street continued to have a long and varied history. Radio production at the site increased significantly under Colonial Radio Company, reaching 631,000 units in 1940. During World War II, the company shifted its entire production capacity to military products. In 1944, the complex was purchased by Sylvania Electric Products Company. In 1948, the plant was reorganized and retooled to produce radios and the first television sets for Sears, becoming the headquarters of Sylvania's Radio and Television Division. However, in 1953, Sylvania constructed a new plant in Batavia, leaving the Rano Street complex vacant. The site remained unused for many years and fell into disrepair, becoming a neighborhood concern. Demolition of the seven-acre site finally began in July 2021, although efforts were made to preserve some historical elements like the clock tower and chimney.

Market Position and Public Perception

Entering a market dominated by established giants like Singer, which was selling a million machines worldwide by 1900, the King Sewing Machine Company initially adopted a strategy of offering a lower-cost machine ($33) and selling directly to consumers through a "factory-to-family" model. This approach aimed to attract budget-conscious buyers and establish a direct relationship with its customer base.

A significant turning point in King's market position came in 1909 when the company successfully garnered the attention of Sears, Roebuck & Co.. Sears' substantial capital investment and commitment to purchase the entire factory output transformed King from a relatively small direct seller into a major supplier for a national retailer. This partnership provided King with immediate scale and access to Sears' vast customer network through its extensive catalog and distribution system. While this arrangement secured a significant market for King's production, it also meant that the majority of its sewing machines were sold under Sears' brand names, primarily Franklin and Minnesota, potentially limiting the widespread recognition of the "King" brand itself.

Despite not always being prominently branded under its own name in the consumer market, the King Sewing Machine Company appears to have maintained a reputation for producing well-made and reliable machines. The company emphasized "modern industry standards" and "absolute interchangeability of parts" in its manufacturing processes. The recruitment of experienced engineers like Frederick Miller, known for his expertise in automatic machinery, further suggests a commitment to quality manufacturing. This focus on precision and quality control likely contributed to the positive perception of the machines sold under the Sears and Domestic brands, which were manufactured in the King factory.

Interestingly, Sears chose to brand some of the machines manufactured in the King factory after 1915 under the "Domestic" name. This suggests that the "Domestic" brand, which had been in existence for approximately 50 years, held stronger brand recognition and consumer trust compared to the newer "King" brand. This decision by Sears highlights the importance of established brand equity in the sewing machine market. While specific market share data for King Sewing Machine Company is not readily available, its role as the primary supplier for Sears, a dominant retailer of the era, indicates a substantial presence in the sewing machine market through Sears' extensive sales channels.

Acquisition by White Sewing Machine Company

In 1924, the White Sewing Machine Company of Cleveland made a strategic move to acquire both the King Sewing Machine Company and the Domestic Sewing Machine Company. This acquisition led to the formation of the White Sewing Machine Corporation, a consolidation that aimed to strengthen White's position in the sewing machine industry. The transaction involved the transfer of rights and some of the property used in the manufacture of King sewing machines to White. By April 1, 1924, the sewing machine manufacturing equipment from King's Buffalo plant was relocated to White's facilities in Cleveland. At the time of the acquisition, King's operations in Buffalo were diversified, with only about one-third of its production focused on sewing machines; the remainder involved automotive parts, cream separators, and radio components. This diversification may have made the sale of its sewing machine division a viable option for King.

Following the acquisition, White reorganized its operations and in 1926 formally became the White Sewing Machine Corporation, integrating the newly acquired King and Domestic companies along with the Theodore Kundtz Furniture Factory, which manufactured sewing machine cabinets. This consolidation allowed White to control a larger segment of the sewing machine production process, from the machine itself to the accompanying furniture. Despite the acquisition, White continued to manufacture some models under the King brand name after 1924. This suggests that the "King" brand still retained some market recognition or customer loyalty that White sought to leverage.

However, the era of White's dominance in sewing machine manufacturing eventually came to an end. The company ceased manufacturing in the United States sometime after World War II, likely in the late 1960s or early 1970s. The White brand continued under various ownership until 2006, after which new White-branded sewing machines were no longer manufactured following a spinoff of the Husqvarna Viking and Pfaff brands into SVP Worldwide. Thus, the legacy of King sewing machines became intertwined with the broader history of the White Sewing Machine Company and the decline of American sewing machine manufacturing in the latter half of the 20th century.

The Collectible Market for Antique King Sewing Machines

Antique King sewing machines hold a certain appeal for collectors, though their value and collectibility vary depending on several factors. Compared to more ubiquitous brands like Singer, King machines might be considered less common, which can increase their desirability for collectors seeking unique or less frequently encountered models.

The value of an antique King sewing machine is influenced by its condition, the rarity of the specific model, whether it retains its original parts and accessories (including the case or cabinet), and the current level of demand among collectors. Early models, such as the first edition King Model that was a direct copy of the Singer 27, might be particularly sought after by those interested in the early history of the company or the evolution of sewing machine design. The close resemblance to the iconic Singer 27 could also attract collectors interested in Singer clones or the broader history of that specific model. While the Singer 27 itself is often considered a common, lower-end machine, the relative scarcity of the King clone might make it more valuable to some collectors.

Online marketplaces provide some indication of the current market for vintage King sewing machines. For example, a vintage electric King machine with an Art Deco design and its original case was listed on eBay for $70 (discounted from $100), with an additional shipping cost of $49.99. This example suggests that while not commanding exorbitant prices, there is a market for these machines, particularly those with unique aesthetic features or in good condition. Some collectors have noted that King machines are "not easy to find," indicating a degree of rarity that could make them more appealing to dedicated enthusiasts of vintage sewing machines. Ultimately, the value of an antique King sewing machine, like any collectible, is determined by what a willing buyer is prepared to pay.

Innovations and Notable Features of King Sewing Machines

Despite its relatively short period of independent operation, the King Sewing Machine Company incorporated several notable features into its products. A significant early emphasis was placed on the production of precisely machined, interchangeable parts. This commitment to standardization was a progressive approach for the early 20th century, promising greater reliability and easier maintenance for consumers.

The initial King Model was explicitly designed as a clone of the Singer 27, sharing many fundamental design characteristics. The First Edition of the King Model featured a curvy 6-spoke handwheel, a belt running inside the handwheel, a wiry shuttle carrier, a tab release tension mechanism, a stitch length adjustment knob located on the pillar, and the serial number placed on the bed in front of the pillar. Subsequent King models often exhibited variations from these initial features, indicating a degree of independent development and adaptation. For instance, later models often incorporated a flattened 3-spoke handwheel with the belt running outside, and the tension release mechanism evolved to an automatic release without a tab. Stitch length adjustment methods also varied across models, with some featuring a knob on the pillar and others a lever on the bed. The location of the serial number also changed over time across different King-made brands.

One identified patent was assigned to the King Sewing Machine Co.: US1348965A, granted on August 10, 1920, for a "Mounting for shuttle-operating levers". This patent suggests a focus on refining the mechanics of the shuttle mechanism, a key component of vibrating shuttle sewing machines. The inventor, Henry E. Smallbone, also held patents for Domestic and other sewing machine companies, indicating potential knowledge sharing or movement of expertise within the industry.

King Sewing Machine Company also adapted to technological advancements by producing electric sewing machines, particularly under the New Willard brand. These electric models catered to the growing demand for electrified household appliances. Some New Willard electric machines were equipped with motors labeled "Domestic" and later "White," directly reflecting the company's acquisition by White Sewing Machine Company. The variations in features and branding across the numerous models produced by King and its associated brands highlight the company's efforts to cater to different market segments and adapt to evolving consumer preferences and technological developments.

Conclusion

The King Sewing Machine Company's history, though relatively brief in its independent form, offers a compelling narrative of early 20th-century American manufacturing. From its ambitious beginnings in Buffalo, New York, the company quickly established itself as a producer of quality vibrating shuttle sewing machines, initially targeting the market through direct sales. The pivotal partnership with Sears, Roebuck & Co. in 1909 marked a transformative period, providing the capital and market access necessary for significant expansion and solidifying King's role as a major supplier for the national retailer. While the majority of its production for Sears was branded under the Franklin and Minnesota names, the quality and reliability of these machines likely contributed to the company's positive reputation.

The acquisition by White Sewing Machine Company in 1924 signaled the end of King's independent existence in the sewing machine market, but the King brand continued to appear on some machines produced by White. The subsequent transition of the Buffalo factory to radio manufacturing for Sears under the Silvertone brand demonstrates the company's adaptability to changing market demands and its continued relationship with the major retailer. The later history of the Rano Street factory, through its ownership by Colonial Radio and Sylvania, further underscores its significance as a manufacturing site in Buffalo for several decades.

Today, antique King sewing machines are of interest to collectors, their value depending on factors like rarity, condition, and historical significance. While perhaps not as widely collected as some other brands, their relative scarcity and the story of the King Sewing Machine Company offer a unique glimpse into the competitive and innovative landscape of the early 20th-century sewing machine industry. The company's commitment to quality manufacturing, its strategic partnership with Sears, and its eventual evolution into other sectors highlight its important place in the industrial history of Buffalo and the broader narrative of American manufacturing.

Sources

- Kelsew.info – The King Sewing Machine Company

- Preservation Ready Sites – King Sewing Machine Company

- WNY History – The Many Lives of the King Complex, Rano Street

- Victorian Sweatshop Forum – King Sewing Machine Company: Models & Mysteries

- eBay listing – Vintage Electric King Sewing Machine

- WGRZ News – Demolition of King Sewing Machine Co. Site

- Still Stitching – Smarter Collecting: Vintage Sewing Machines

- Bay News 9 – Demolition Begins at Former King Sewing Machine Site

- Patented-Antiques – Antique & Vintage Sewing Machine Value Info

- Dincum – Old Sewing Machines: American Manufacturers

- Fiddlebase – White Sewing Machine Company

- Scripophily.com – White Sewing Machine Corp. Bond Certificate

- Treadle On – White Sewing Machines

- Encyclopedia of Cleveland History – White Consolidated Industries

- Wikipedia – White Sewing Machine Company

- PatternReview.com – Singer 27 Discussion