William Jackson's Sewing Machines

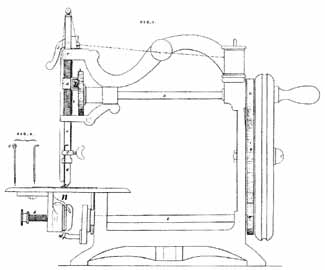

Figure 1

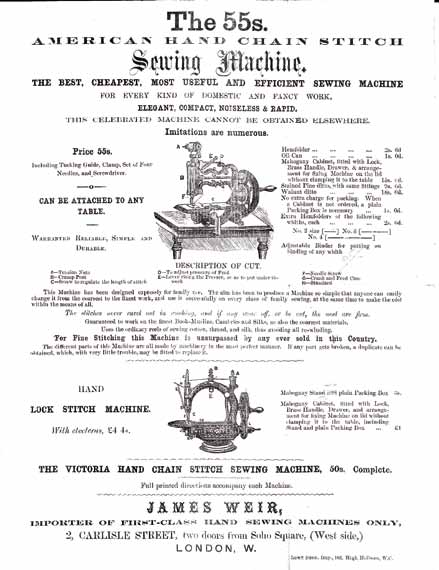

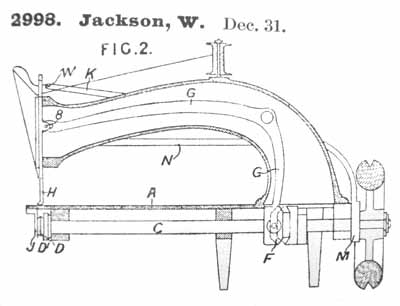

Jackson's 1859 patent for a rotary hook machine

Alan B. Wilson's stationary bobbin rotary hook machine for making the lockstitch was patented in 1851, right at the beginning of sewing machine production.

Although the stationary bobbin, rotary hook principle is the basis of most sewing machines today, the principle was not widely used in the nineteenth century compared with the shuttle lockstitch. Wheeler & Wilson was the only major manufacturer to use it exclusively.

In England, clones of the Wheeler & Wilson curved needle machine were produced in quantity by many manufacturers. There were few indigenous designs of rotary hook machine and none of these was commercially successful. One that springs to mind is the Starley / Coventry Sewing Machine Co. 'Express' of 1868, made for the Howe Sewing Machine Co. for sale in England (see ISMACS News 101, pp29-31). This was the Starley's only rotary hook machine and few were made.

One small scale manufacturer who remained faithful to the rotary hook principle over many years was William Jackson. Jackson was a Yorkshire engineer who took out his first patent (Figure 1) for a large industrial free arm lockstitch sewing machine in 1859 after he moved to London and was living in York Road, Lambeth. His machine used a rotary hook mechanism copied from Wheeler & Wilson.

The thin bobbin was held in a recess in the hook disc by a ring similar to the W&W curved needle machine. The hook itself was a much simpler and cruder device and there was no checkbrush to retain the loop when cast off by the rotation of the hook. To remedy this, Jackson's patent refers to a 'spring wire' (W) to keep the thread taut when the loop is cast off.

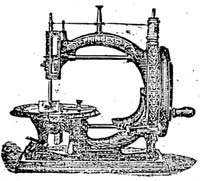

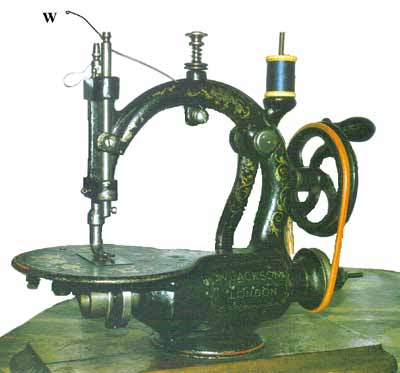

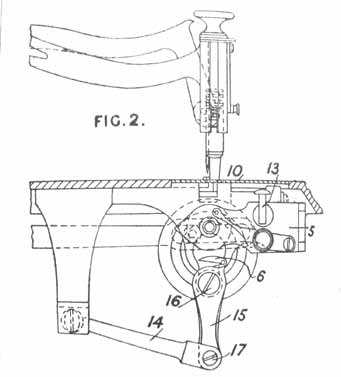

Figure 2

Jackson's first type of domestic hand machine (W is the spring take-up)

Jackson went on to patent various improvements to boot and shoe sewing machines. By 1867, he had a shop in Eaton Square, Pimlico, London where he marketed a domestic hand machine using the ideas of his 1859 patent (Figs. 2 & 3).

This retained the 'spring wire' to keep the thread taut. It was not a success and James Weir bought up the redundant stock around 1870 for sale through his offices. Very few have survived.

Figure 3

Bobbin assembly and retaining ring for the first type of domestic machine

Figure 4

Jackson's 1872 patent for the "Automaton" hand machine

Figure 5

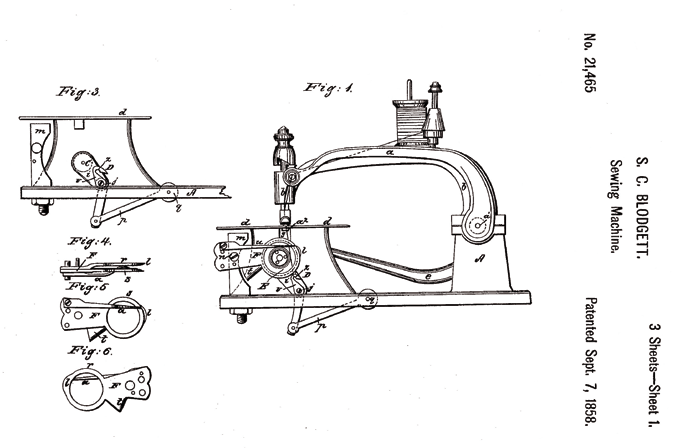

S. C. Blodgett's patent for the 'Elliptic' machine

Figure 6

An 'Elliptic' sewing machine showing the rotating hook and stationary bobbin

Figure 7

Alexander Pilbeam's version of the 'Elliptic' mechanism, 1863

Figure 8

Fig. 8, the 'Automaton'

By 1871, Jackson had moved out of London to the countryside at Warlingham, Surrey where he both lived and had his workshop. There he manufactured velocipedes and carriages in addition to sewing machines. His second form of domestic machine was called the 'Automaton'. He took out a patent for it in 1872 and incorporated a type of rotary hook mechanism originated by the 'Elliptic' sewing machine in America. Jackson's patent did not seek to cover the hook mechanism; it was to cover the needle clamp for a special needle with a tang located in a hole in the needle bar, and the wire loop spreader for the bobbin (n on Fig. 4).

The mechanism of the 'Elliptic' machine was patented (Figure 5) by Sherburne C. Blodgett in 1858 and assigned to George B. Sloat. It is often known as Sloat's Elliptic (Figure 6). The rotating hook picks up a loop of thread to take round the stationary bobbin but, because of the link (p on Fig. 5) to the frame, always remains facing in the same direction. The loop has to be detached from the hook by a finger. The original 'Elliptic' machine looked like a Wheeler & Wilson machine and some were even made by Wheeler & Wilson! The first British manufacturer to use the principle was Alexander Pilbeam in 1863 with a straight copy of the Blodgett mechanism (Fig. 7).

When Jackson used the idea in his 'Automaton' he simplified the mechanism and omitted any form of thread take-up, not even a 'spring wire'. The 'Automaton' (Figs, 8, 9, 10) sold for 4 guineas (£4. 4s), the same price as the 'Agenoria' of very similar outline and size.

Figure 9

The 'Automaton' (rear)

Figure 10

The 'Automaton'

Figure 12

Note the reversed "S" in the casting of Jackson's name on the stand.

Figure 13

The bobbin assembly of the "Automaton"

Figure 15

The hook passing the needle to pick up a loop

Jackson even commissioned his own single pillar stand which was available for £6 (Figs. 11 & 12). The machine seems to have been designed to be cheap to produce in a simple workshop. The complete frame, including the clothplate, was one casting and, as no machining was required, could be bought in from a foundry ready-japanned.

All that Jackson's workmen had to do was to drill and spotface 10 holes for shafts; drill and tap 8 holes with screw threads, then drill half a dozen oiling holes, etc, before fitting the moving parts and applying the decoration. None of the mechanism had any provision for adjustment to allow for wear or misalignment. The under-thread was carried on a small brass bobbin mounted in a brass bobbin-case (Fig. 13).

The simple bobbin winder was driven by a belt from the balance wheel, though you have to unthread the machine first as there is no loosewheel fitted although the castings would allow for one.

William Jackson continued to file patents and produce sewing machines into the 1880s, though latterly concentrating on his boot and shoe machines. He left Warlingham and moved back to London using his old address in Pimlico. The 'Automaton' machines do not carry serial numbers so we have no idea how many were made. Not many 'Automatons' survive, suggesting that it was much less popular than its direct competitors such as the 'Agenoria' and the 'Shakespear'.

Maybe seamstresses were put off by its rotary hook mechanism while they were familiar with simple shuttle machines. Having tried to sew with it, I think I can see why.

The hook picks up a loop of thread and carries it round the stationary bobbin reliably (Fig. 15) but, with no positive take-up mechanism, the cast off loop is not pulled tight until making the next stitch when, if the top tension is tight enough, the rotating hook tightens the preceding stitch before drawing out more thread from the reel. The top tension has to be near the breaking stress of the thread.

In the 1870s, six-cord sewing thread (ONT) was available but not universal. I suspect there was much cursing of broken threads even though a thread oiler was fitted to lubricate the stitches.

Figure 11

The 'Automaton' on its single pillar stand

Figure 14

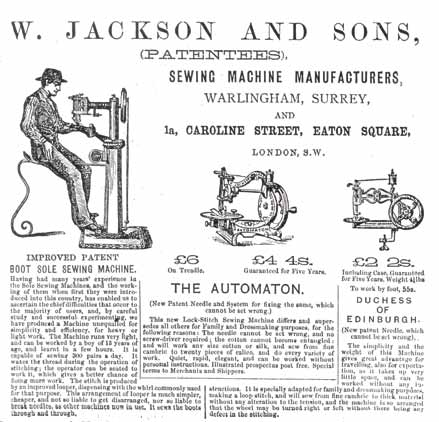

An advert for Jackson's machines dating from the mid 1870s (Right) Fig. 16, advertisement showing Jackson's first hand machine for sale from James Weir