James Gresham

Engineer and Art Collector

1836-1914

Charlie Hulme tracks down a sewing machine pioneer: the man, his life and times… and some of his achievements.

James Gresham was born on 28 December 1836, at 13 Castle Gate, Newark, Nottinghamshire, to Richard and Elizabeth Gresham. He had an elder brother Robert and an elder sister Elizabeth. Richard Gresham was a seed merchant: he died while James was a baby, and his widow Elizabeth later re-married to become Elizabeth Reynolds.

James was educated at the Grammar School in Newark. At the age of fifteen he broke his leg in an accident. It was decided to send him by coach to Lincoln, 16 miles away, for the attention of a bone-setter. Unfortunately, the coach overturned and he broke his collar-bone as well as doing further damage to his leg. He was returned to Newark, where a doctor amputated his leg above the knee - most likely without anaesthetic. He was supplied with a primitive wooden limb, which he proceeded to improve upon by inventing an artificial leg that would allow him to walk almost normally. Showing early business acumen, he sold the design to a maker of surgical appliances.

While restricted in mobility, he took to drawing and painting and in 1855 he headed to London, using the remaining proceeds from the artificial leg to enrol at the South Kensington School of Art. While there, Gresham came to realise - with advice from Frith and other tutors - that although he was a naturally skilled draughtsman and excelled at copying the works of other artists (Daniel Maclise was a particular favourite), he lacked the artistic inspiration to create an original painting.

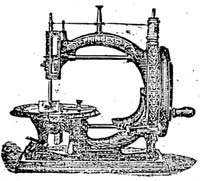

An early Gresham

In 1856, he noticed an advert in an art journal for a 'sketching clerk' to assist the secretary of the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition, to be held in 1857, and became assistant to George Scharf, secretary to the committee, whom he already knew from his visits to the South Kensington School (Scharf was the first director of the National Portrait Gallery).

Gresham's role in Manchester was to help organise the exhibits and make drawings and pictures of this remarkable event which took place in a specially built glass-and-iron building palace, covering three acres of the Botanical Gardens in Old Trafford, just outside Manchester. The exhibition was open from May to October 1857, and attracted over 1,300,000 visitors.

The exhibition over, and all the treasures returned to their owners, Gresham was in need of another job. He found one at the Atlas Works of Sharp Stewart and Company in Manchester city centre, makers of textile machinery and railway locomotives, where he trained as an engineering draughtsman. There, he first turned his hand to improvements in Giffard's 'injector' for steam locomotive boilers. He also contributed to the company's textile machinery, design- ing an improved machine for winding sewing thread onto bobbins. (See Martin Gregory's article in ISMACS News #88.)

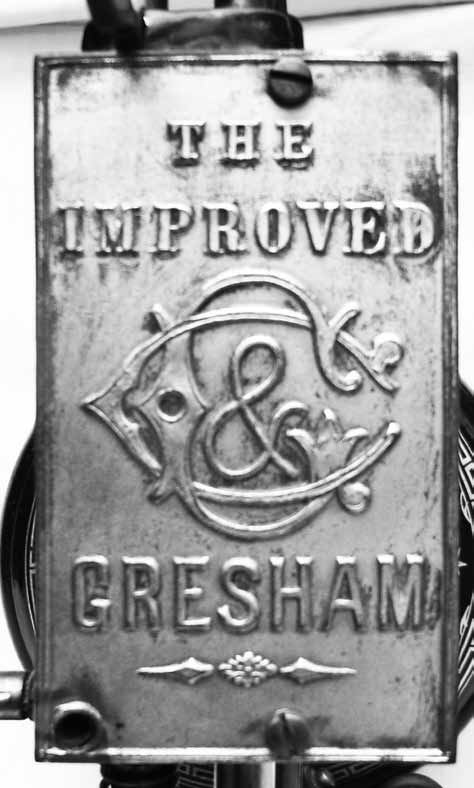

The 'Improved Gresham' front-plate

In 1861, he married Louisa Jane Horseley, a native of Gunthorpe Lodge, Lowdham, in his home county of Nottinghamshire, who is described by his grandson Colin as "a very strict Victorian wife, who kept her husband and children under firm discipline". She would have been supported, in the early years of the marriage, by Martha Battle, apparently his wife's grandmother, who the 1861 census records as living with James and Louisa in their little house at 49 Rutland Street, Chorlton-on-Medlock; not far from the Atlas Works. For some reason he exaggerated his age to the census-taker, describing himself as 35.

In 1865, after an argument with Sharp Stewart over his salary, Gresham left the company and headed off with his wife and two children (Adah and Harry) to London where he worked for a while at the Whitechapel Iron Works. However, a few months later he was back in Manchester, where he worked as a self-employed engineering consultant. He advised firms and invented various gadgets - including an egg-boiling pan with built-in timer - whilst working on plans to create a practical sewing-machine; an idea he picked up while in London from a financier named Ira Dimmock. The two of them patented a sewing machine (No. 636, of March 7th 1867).

Gresham - in partnership with Mr Seward, a brass founder from Sharp Stewart and (a financier) Mr Heron - set up business at a factory in Ordsall Lane, Salford, to make locomotive injectors. The sewing machines were contracted out to Wren & Hopkinson. More capital was required to expand the business and this was supplied by Thomas Craven, so that the company became Heron, Gresham and Craven.

By the 1871 Census, Gresham was living at 16 Wilton Street, Chorltonon-Medlock, with his wife Louisa Jane and their children Adah (aged 9), Harry (6), Samuel (3) and Frank (11 months); describing himself as "Master Engineer, employing 28 men and 15 boys". He gave his age more accurately this time, as 35. Now very much of the middle-class - they had a live-in 'domestic servant', Mary Collinson.

Mr Heron left the firm due to illness and the firm took on the name 'Gresham & Craven'. Their injectors were very popular but they had less success with their sewing machines; eventually leaving the field to mass-production makers, such as Singer, who could bring the sewing machine to the masses.

On the earlier version, the monogram decal reads H,G&C. There were only two versions of the sewing machine and they are mechanically the same.

From 1878 they were manufacturing and selling an effective automatic vacuum-powered braking system for railway vehicles, which went on, in improved form, to become the standard for most railways in Britain and across the British Empire.

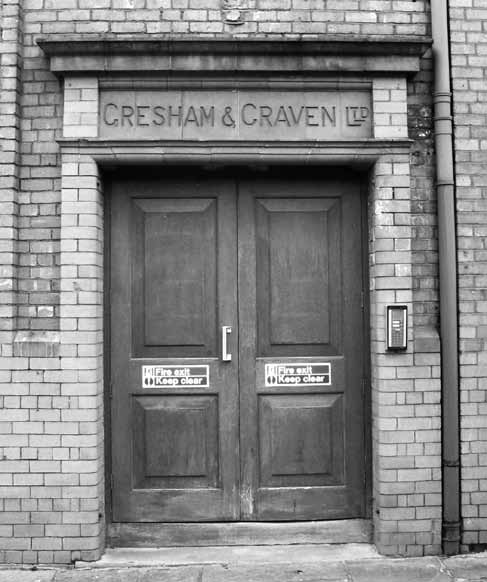

Gresham and Craven were taken over by their competitors, The Westinghouse Brake and Signal Co. in 1954. The collapse of a British Railways contract for brake equipment spelled the end of the Ordsall Lane and other works, leading to total closure. Remaining activity of the company was transferred to the Westinghouse factory at Chippenham by 1966. Happily, at the start of the new century, part of their factory in Salford has been restored as office accommodation; with the name 'Gresham & Craven Ltd' in large lettering visible to travellers on the Metrolink trams, between G-Mex and Cornbrook stations on the north side of the line, and a nearby development of apartments is named 'Gresham Mill'. An engineering firm called 'Heatly and Gresham' is still in existence in India. This was founded by James' son-inlaw, Harry Heatly, in 1892 to look after their sales to Indian Railways.

Louisa Jane Gresham died in 1876. In 1887 came James' surprise announcement that at the age of 50 he had married, in London, Helen Amelia Myers, an "attractive mature woman. Very different from his first wife". Not only that, they had a baby daughter, named Millicent.

The diestamp has the space for 'Heron, Gresham & Craven' but Heron's name has been milled out rather than making a new stamp.

The new Mrs Gresham was not keen to live 'up north' but, some time around 1905, James moved his first family into a bigger house, 'Ashleigh', in Woodheys Park, later known as The Avenue, in Ashton-upon-Mersey; then in countryside outside Manchester. Gresham re-named the house from 'Ashleigh' (or Ash Lea) to 'Oak Bank' after his earlier home, and later to 'Gallery House' after he added a private art gallery.

In his new home, Gresham indulged his lifelong passion for art. For years he had been collecting paintings, taking care to patronise living artists, especially his friend W.P. Frith, from whom he bought nearly 50 works. In 1887, he served on the committee organising the Royal Jubilee Exhibition, which took place on the same ground in Old Trafford as the 1857 exhibition which first drew him to Manchester.

Gresham's philanthropy also included a contribution to the building of a new School of Science and Art in his home town of Newark, opened in 1900.

James Gresham died on 13 January 1914 and, according to his wishes, was cremated; the ashes were deposited at Manchester Crematorium. He left money to several local hospitals, and several paintings from his collection to the Manchester Art Gallery. His children inherited his shares in Gresham & Craven, where all the sons worked. Gallery House and the paintings passed to his widow Helen. In the case of the house, this was on condition that she promised to live there at least 180 days per year. She refused to do this and everything had to be sold. She received an annuity and bought a house in Richmond where she lived until her death, in 1918.

The restored factory in May, 2010

Gallery House, with its extensive grounds, was left unwanted. Nobody needed such a mansion in the post-war world with its shortage of servants. Especially one with an art gallery attached. Its fate is a little obscure. It appears from available information that the land was sold to a builder called Mr Dean. He had the house demolished and built a large bungalow for himself, reviving the old name of Ashleigh, and building houses for sale on some of the remaining land. The curving drive to the house from The Avenue is now a wooded cul-de-sac named 'Moorwood Drive'.

The servants' cottages in the grounds are still there, as 7 to 13 Moorwood Drive, and No 7 still bears the name 'Gallery Cottage.' An old outbuilding also survives, in poor condition, and the gateposts at the start of the cobbled drive still stand as a memorial to Gresham and his private art gallery.

~ Charlie Hulme

Gallery Cottage

The Gresham No.1

The author outside the gates; all that remains of the Gresham home.

If you can add to this story, especially if you have photos of Gallery House, please contact the author: [email protected]

Photos: Martin Gregory, Graham Forsdyke and the author.

Reprinted by permission from the John Cassidy website: www.johncassidy.org.uk