Hermann Loog

CHECK OUT that early Frister & Rossmann in your collection, or practically any other German machine. There's a good chance it will carry the label of Herman Loog. "

OK, we could cut this short with me giving you a brief history of Loogs company and leave it at that."

So, to tempt you into reading this piece, let me tease you by revealing that, in April 1904, HL calmly walked into Croydon Cemetery, put a pistol to his temple, and ended his life."

The following is my poor attempt to explain what drove a successful businessman to suicide after a few short years."

It is compiled from press reports and gossip of the time.

GF

HERMANN Loog was born in Germany in 1845 and, after a first-class education, was articled for four years to a Jewish banker in Berlin. When about 20 years old he came to England and entered a mercantile office as foreign-correspondence clerk."

By this time he had almost mastered three languages besides his mother tongue.

Eight years later Hermann Loog starts in business for himself in London as a wholesale hatter, and in 1876 he contrives to obtain the wholesale agency for the United Kingdom for Frister & Rossmann's machines, which was previously owned by Mr. Isidor Nasch.

Within a very short space of time hats were relegated to the background. At this time Singer was still at war with other makers over the question of trade name and Hermann Loog, who was ever a fighter, could not do other than take a hand in the contest.

Accordingly he used the word Singer to describe one of the machines made by F&R in Berlin. A lawsuit followed and after total defeat in one Court then a partial win, he succeeded in the House of Lords.

From this time forward Hermann Loog could never get rid of the idea that he had done a great workhe had beaten the Singer Company as a far greater man than he, Newton Wilson , had failed to do so.

It is strange, however, that he could never realise exactly what he had achieved, which was merely this: he had used the name Singer as a descriptive term to a man in the trade who knew that the world was merely descriptive and he was not and could not be deceived.

Newton Wilson , on the other hand, wanted to use the word Singer in transactions with the public, which the Courts could never be brought to permit. Newton Wilson died a poor man as the result of unsuccessful litigation with Singer , and the Loog three years later follows him to the grave with a self-inflected bullet wound as the result of success in the law courts!

Why success in law should have brought disaster in business may require some explanation. Loog at first only did a wholesale trade, and in the second year made nearly 1,000 clear profit, to secure which, in the face of possible failure in the courts, he registered his business as a limited liability company in 1879.

When, in 1882, the House of Lords decided in his favour, Loog determined to copy the Singer Company's plan of opening depots in all the principal towns.

Hermann Loog had now a bee in his bonnet he had whacked the great Singer company , and to the day of his suicide he considered this his life's work.

Wherever Singer had a shop in the south of England, Loog also must have one, yet better located and more elaborate, if possible, and the town must be flooded with circular matter referring to the trade-name lawsuit.

This went on until the depots selling sewing machines and other useful articles for the home numbered 38, including the handsome and capacious headquarters at 126 and 127 London Wall, EC.

Loog worked like a fanatic to his last day. He lived at Brighton, going down each night at six and leaving home each morning at 6.20, so as to be in town as soon as the first post was delivered.

On arriving at London Bridge Station he would cross over to the Turkish Baths opposite and spend a half-hour in the hot rooms, being loaned a private key by the proprietor, as no one was in charge at this early hour of the day.

But neither Loogs pocket nor that of Frister & Rossmann could stand the pace, and the vanity which had influenced him to neglect his profitable wholesale trade for rivalry with Singer was destined to make with a rude awakening.

It came about in this way: Hermann Loog Ltd was only a one-man company, himself owning all the shares but six. In 1885 there occurred some mysterious proceedings which upset the confidence of a couple of the largest creditors, followed by a Press view of a rotary sewing machine, called the Fox, which the concern was proposing to manufacture, in spite of it conflicting with the interests of Frister & Rossmann Ltd.

In September, 1886, a petition for voluntary winding-up was presented and three months later F&R got a receiver appointed to look after its interests, which were represented by 32,000 in debentures.

Events now followed rapidly. Just after Christmas 1887, Loog was arrested together with his son, a boy of 18, and brought up at the Guildhall. The father was on a charge of fraudulently applying 8,000 to his own us and of illegal pledging goods belonging to F&R, and the son of being an accessory in the culpable omission of the father to make certain entries in the books belonging to F&R.

Both defendants were committed for trial, but when brought up at the Old Bailey the jury very soon stopped the hearing, returning a verdict of not guilty.

During the next few months Loog tried to get someone with capital to re-open his old showrooms and offices at 126 and 127 London Wall and start a similar business, as the liquidator of Hermann Loog Ltd had vacated these premises and was declining to do further trade, merely selling off the old stock and collecting the 20,000 installment accounts.

Mr. George Whight, the surviving partner in Whight & Mann whose sewing-machine business was founded in 1859, and who carried on a sewing-machine and musical-instrument business at Holborn Bars, EC, was ultimately induced to listen to Mr. Loogs pleadings. In September 1886 Loog was installed at his old premises in London Wall as manager for George Whight & Co with, practically, his old range of goods except another make of sewing machine in place of the Frister & Rossmann.

Business, however, was not as profitable, although a large trade was done, resulting in a loss during four years of several thousand pounds. Various reasons are given for this. Some say that credit, particularly to the working classes, was the cause of failure and others that Loog, who certainly worked very hard, as usual, had his mind too much occupied with lawsuits.

Two of these actions arose out of the earlier prosecutions with Loog and his son, attempting to claim damages from F&R for malicious prosecution.

The sons case was taken first, but on 1 February 1888, the jury found that F&R honestly believed the charge to be true, and gave judgment for the defendants, whereupon the father elected not to proceed with the second action.

In June, 1888, Mr. George Whight, whose connection with Hermann Loog was costing him dearly, had to defend an action by Frister & Rossmann alleging that during Loogs liquidation Whight had been treated preferentially.

Baron Huddle-stone, however, sum-med up the case to the jury strongly in favour of Mr. Whight for whom a verdict was given.

But Whight had had enough of Loogs problems and in 1889 dismissed the German entrepreneur. But Loog sprung back a year later, opening a large shop at 34 Newgate Street, EC, stocking it with Seidel & Naumann sewing machines and musical instruments.

Here he was known as the Co-operative Trading Company, but not for long, as within six months he and his partner, the young son of a German banker, were at loggerheads with more acrimonious lawsuits and another winding up.

This time creditors were assured that they would get all their investment returned but eventually, after months of delay, the most that was ever paid out was 10%.

Loog, in July 1890, opened a domestic- machinery store at 85 Finsbury Pavement, EC, continuing to act as Messrs Seidel & Naumann's agent for a few months longer.

In the meantime the liquidator of Hermann Loog Ltd brought an action against Lloyds Bank of a peculiar nature.

Loog possessed much personal magnetism and he had succeeded, as no one else had done before or since, in getting that bank to lend him money on hire agreements as security.

So much had been borrowed on the agreements that nearly 6,000 was owing to Lloyds Bank. The liquidator was called upon to collect the outstanding installments, which he did at a cost of 10 shillings in the pound, and the bank contended that the cost of collection should fall on the rest of the creditors.

The High Court, however, decided otherwise, with the result that Lloyds Bank lost over its practice of lending money to Hermann Loog on his hire agreements some 3,000, or half the money it advanced.

The winding-up order of Hermann Loog Ltd, granted on 22 January 1887, was only brought to a close on 23 June 1891. So numerous were the bad debts and so costly were the collections and the law proceedings that the dividend paid to the creditors, including F&R, only amounted to four pence in the pound.

Loog was constantly involved in bankruptcy proceedings. A receiving order had been granted against him in 1879 with liabilities of 11,243, and upon which he paid a dividend of half a crown in the pound, and was then granted his discharge. In 1888 he again failed, this time with liabilities returned at 5,740, paying no dividend whatsoever, and not applying for his discharge.

December 1890 again finds him in the Bankruptcy Court, although undischarged, with liabilities of 1,200 and no assets, except a questionable claim against Seidel & Naumann for 1,000 for breach of contract.

The Finsbury Pavement business, like the others, failed to succeed, whereupon Loog invented a fantastic trading scheme under which the public was to get articles for the home at wholesale prices which is registered in July 1892, as Hermann Loog New Company Ltd, with a capital of 2,000. Not surprisingly he failed to interest sufficient inventors.

A year later he agrees to act as wholesale agent for the Midland Perambulator Company, which connection was a stormy one, and lasted but three years.

In February 1897 he again failed, although his discharge from two previous bankruptcies had not been granted, his liabilities this time amounting to 250, but no assets.

In the meantime the Finsbury Pavement business, which had been opened and closed several times, had its door closed forever so far as concerned Hermann Loog.

A new era would appear to have dawned for Loog in May 1897, as he was then engaged to take charge of the sewing-machine department of the well-known firm of Faudel, Phillips & Sons at its Newgate Street warehouse.

Here he strove to develop a big business, keeping 10 girls employed with typewriters, flooding dealers with Victorian junk mail.

Illness, however, gradually but surely undermined his constitution. Loog remained at this post nearly six years then, for reasons unknown, he left, and in July 1903 entered the service of Mr. Alwin Eichler of 103 St John Street, London EC, which is an American publishing house selling fiction.

This was his last employment and here he worked as strenuously as of yore, the first to arrive in the morning, never pausing for a meal, the last to leave at night, and always taking away work to do at home.

There remains little more to be said of this remarkable man.

On Wednesday 18 May, he left business at mid-day and appears to have made his way direct to the Croydon Cemetery, arriving there at 2.30 and paying 7s 6d for the maintenance of the grave of his wife who, after being in the City of London Asylum for some years, was buried in Croydon Cemetery on 13 March 1902.

He had a conversation with Mr. Bird, the Cemetery Superintendent, on the subject of religion, expressing the idea that there should only be one religion, and telling him that his first child, who was buried with his wife 20 years ago, had been refused a Christian burial because he had not been baptised.

Two hours later the Superintendent was called to a spot near Mrs. Loog's grave, where he found the husband with a bullet wound in his head and quite beyond human aid.

At the subsequent inquest, an employee of Mr. Eichler said that there was nothing wrong with Mr. Loog's accounts, and Mr. Bird stated that the deceased had told him shortly before taking his life that he had had a lot of trouble, and for seven years could not write and he got his living with his pen.

The police produced a typewritten letter, which was read by the Coroner, as follows:

I particularly ask some hospital to accept my body for the study of a complaint which for years has puzzled the medical men. For the last three or four years I have been nothing short of a perambulating drug store, and a good few doctors expressed themselves puzzled at the symptoms.

Dr Clay of 15 Acre Lane has full particulars of my long illness, and I wish him to be asked first, and let him, or any hospital he names, have the first refusal of the offer.

I am very little good alive, but I may be some little good dead, and I hope it can be arranged. Hermann Loog 18 May, 1904.

PS I have no friends, no relations, and nothing to live for.

The proceedings at the inquest were brought to a close by a doctor deposing that death was due to a bullet wound in the head and the jury returning a verdict of Suicide whilst of unsound mind, and the remains were subsequently interred in the Croydon Cemetery.

The statement that he had no relatives living was possibly incorrect as his son, Robert, who at one time was clerk in the office of Seidel & Naumann at Dresden, was known to be alive a few months earlier, and is thought to be residing in America.

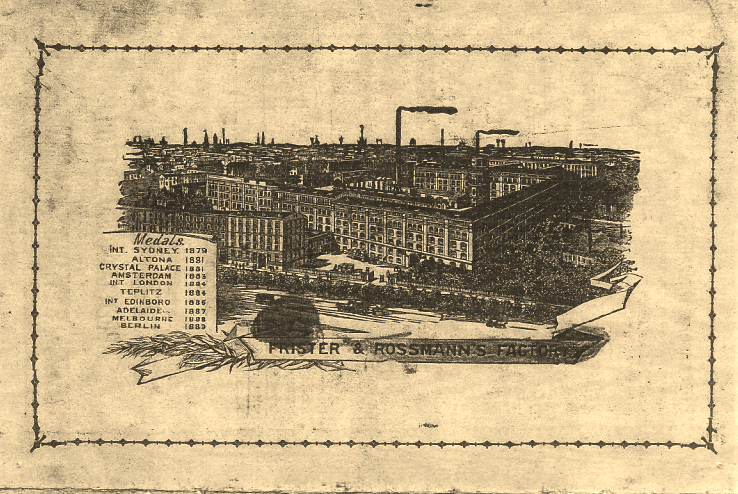

Frister and Rossmann Sewing Machine Factory