Florence History - The Fabulous Florence

Most desirable of the Florence treadles, this version, known as the fancy or pierced-leg, actually uses very fine iron castings and intricate decoration to give a very delicate effect. Drive is by flat belt from the count-shaft, which also supports the fly-wheel.

SOME 14-ODD YEARS ago a crowd gathered on the edge of a field in Brimfield, Massachusetts to watch a crazy-looking Englishman attempting to dismantle a treadle sewing machine with the aid of a bent electrician's screwdriver and a rusty pair of pliers with one broken jaw. I was that Englishman and the machine which finally came apart to fit in a friend's car was a Florence - the first American machine bought in that country to add to the MS collection.

Earlier this year that same scene was repeated, this time in a Vermont barn, where another Florence machine was broken down before making the trip to England. All of which goes to prove, that although the Florence machine rates highly on any collector's wants list, it isn't that rare of a beast in the New England area where it was originally made.

At least three of our members have gone to the States and come back with Florence machines. But this plethora of models is more a tribute to the original craftsmanship than its popularity when made, for the archives suggest that no more than 100,000 were ever completed in the 20-odd years of the company's existence.

The story started in October, 1855, when Leander W. Langdon (with a name like that he had to succeed) took out his first sewing-machine patent. He started sewing-machine manufacture a year later, producing a few machines under his own name in his home town of Northampton, Mass, but without any great success. It was a classic case of under funding and he set about raising the capital to get into business on a more workman-like scale. Three years later he had raised the capital and chose the small Massachusetts town of Florence to set up his factory.

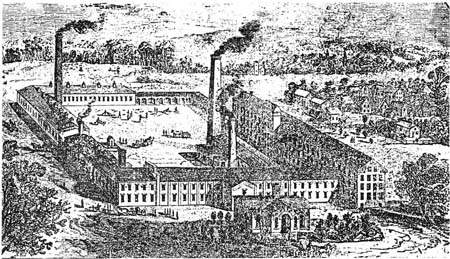

This faded woodcut shows the Florence factory in its prime and suggests not one, but three, steam engines in operation. The factory area was said to cover three acres.

The small business grew rapidly, the machine-hungry people of New England instantly warming to a good-quality, locally-made product. Within a few years a purpose-built factory was at full steam. The works building was set in three acres of ground and, at its height, employed 350 men. The ground floor was given over to foundry work and japanning. One floor up, all small parts were made, leaving the top floor for assembly and testing.

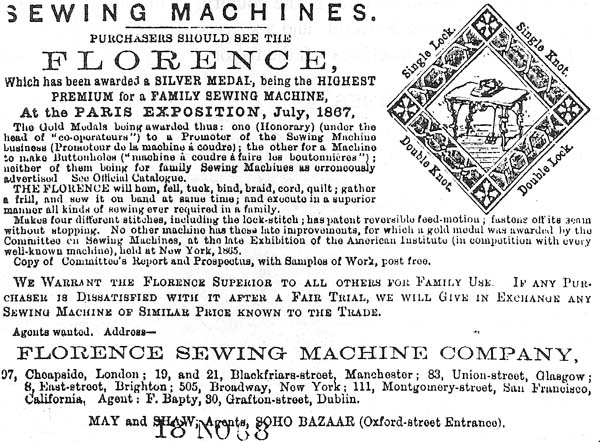

This advertisement from Queen magazine was typical of those which appeared in this country in the 1860s and boasts of what appears to be the Company's only major international competition success - a silver medal at the Paris Exposition in July of that year. The advertisement was placed by main London agents May and Shaw who had offices in the Soho Bazaar - a busy London indoor market.

One giant steam engine located in an outbuilding provided power for the entire factory, driving the bellows for the foundry, the machine tools for small-part manufacturing and even the top-floor area where all completed models were run under steam power for testing. But by around 1879 the sewing-machine bubble had burst and Florence, like so many similar companies, went to the wall.

The record books of the business show a strong, if unspectacular, advance in sales until a peak of 17,600 in 1870, making them the sixth-largest manufacturer in the country. From then on it was downhill and six years later less than 3,000 machines left the factory. It was a tough time for all, and of the scores of American manufacturers, only Singer was able to show any growth over this period. An attempt to revitalise the company was made in 1873.

Until then most Florence machines, and those of other manufacturers, were sold by canvassers who toured the country with wagons seeking to demonstrate the machine

and offer it on a month's free trial. After the month was up it was then possible to buy the machine on hire purchase - a system first introduced by Singer . In 1873 Florence did away with all that. The company decreed

that it would sell for cash only. Its point was that the system of hire purchase and canvassers produced sales mainly to the "thriftless and unprincipled and, therefore, the honest customers were having to make up for the bad debts of others". In the future, Florence decreed, there would be no HP, no canvassers and no trial periods. As an inducement to get the new deal going, all prices were slashed by up to 25 percent.

Towards the end of its days, even the London officers, by this stage at Queen Victoria Street were offering cut-price deals.

Thinking that perhaps a change of name might improve fortunes, the company re-christened its machines in about 1879 to Crown and later to New Crown, but no examples of either re-named machines are known to exist.

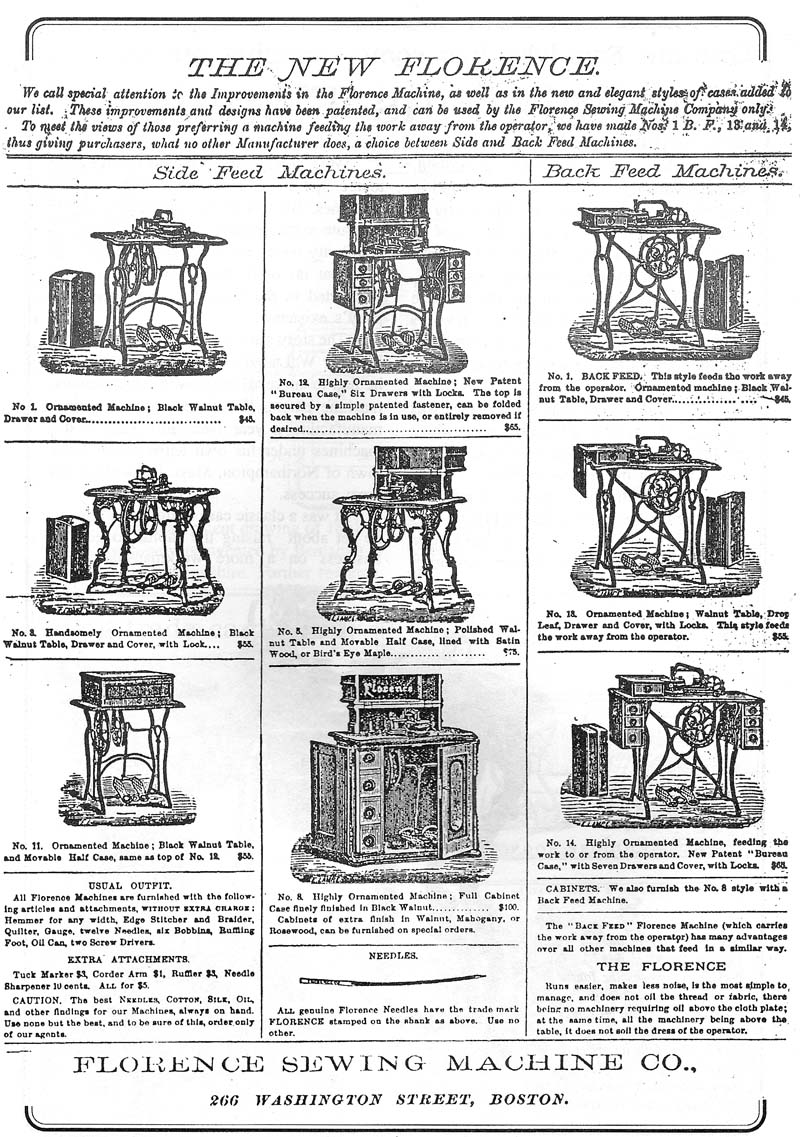

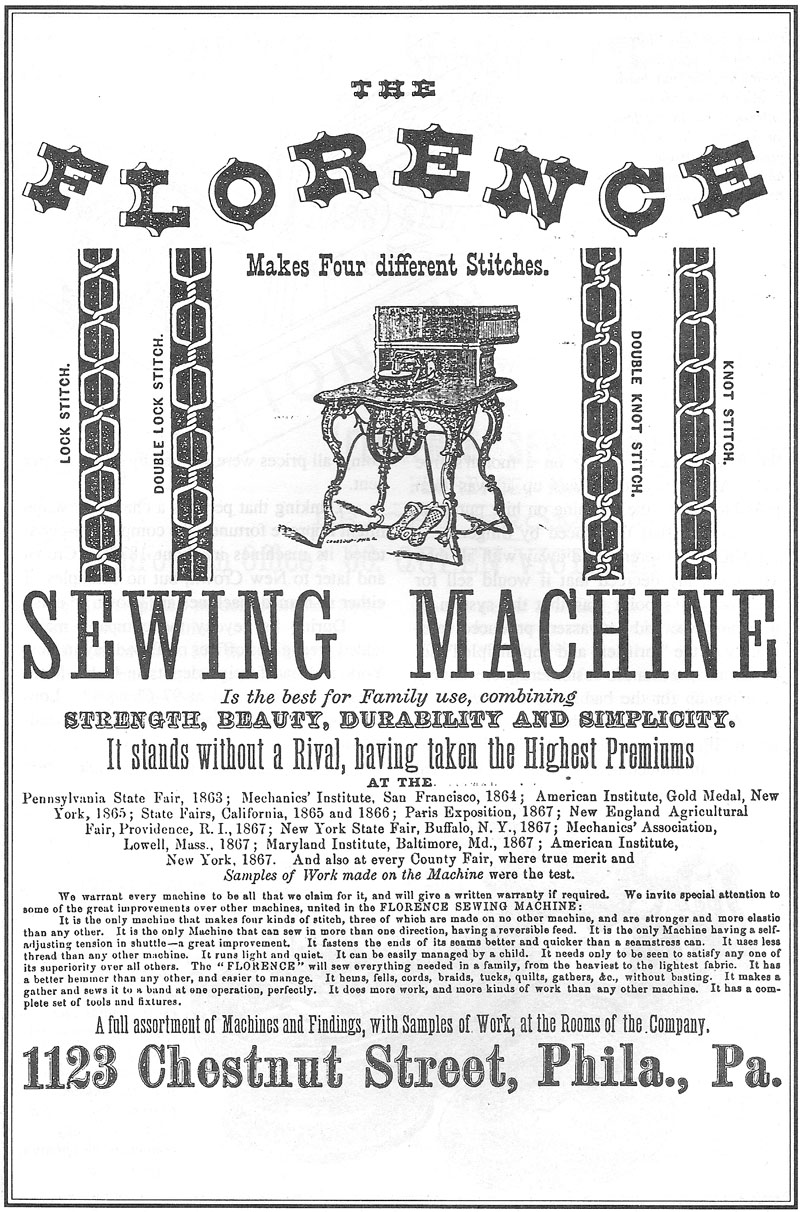

Although not the flag-ship of the range, the fancy-leg treadle was often used in advertising campaigns as in this early English Example.

During its heyday the company maintained prestigious offices on Broadway in New York and had foreign depots in Cuba, Manchester, Glasgow and at 97 Cheapside, London, which was dubbed the European headquarters. And it was from that Cheapside address that a strong advertising campaign was mounted during the early 1870s. Advertisements appeared in most British newspapers and magazines but strangely, to my knowledge, no Florence machines have ever been found in this country.

The main selling point of the Florence was its reversible feed, allowing the clean finishing of hems and other work. The machines were available with either side feed where the work was drawn from left to right or back feed as in most conventional machines. Surprisingly, it was the side feed that seemed more popular for, although I have seen many side-feed models, I have only encountered two back feed varieties - both in the collections of ISMACS members.

Two very distinct heads were available. One was decorated with simple gold lines but the other, with intricate fine lace-like decor and floral design, produces one of the most attractive sewing machines of all.. Numbering , for what it is worth, seems to indicate that both heads were available at the same time.

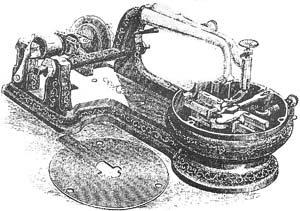

The official factory woodcut which was used to illustrate encyclopedias and many other reference works dealing with sewing machines. It clearly shows the unusual Florence feature of a stitch plate easily removable by operating a spring clip.

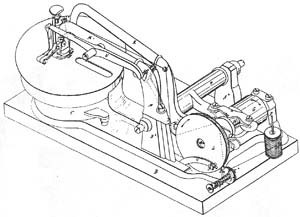

Unmistakably a Florence, this patent application from Langdon was made in March 1860 to cover improvements in the feed mechanism. It places great stress on the advantages of using cranks rather than cams.

The basic Florence machine with plain treadle sold for $45 in 1873 with another $10 being required for the ornate "pierced" legs which have become a Florence trademark to the present-day collector. Despite the relative expense of the ornate-legged variety, the two treadles turn up today in roughly equal quantities. I have never seen the top-of-the-range machine which featured a full cabinet in black walnut, rosewood or mahogany, but at over twice the price of the basic machine, it was probably a rare commodity even when new. Silver plating was available on all models. Limited to the cocking and stationary arms and to a few fittings, it was listed as a $6 extra.

The best of the Florence's must be the hand-operated model owned by Cathy Racine in Charlton, Mass. This model has a Forth-Bridge-type gantry built above a conventional head to carry a hand wheel. I have not seen another nor any reference to it in advertisements. It turned up very near to the town of Florence and could have been a factory prototype or a model which was never put into full-scale production.

Today the Florence remains one of the most aesthetically-pleasing machines of all which, despite its lack of rarity, commands high prices whenever offered for sale.

American Advertisement dating from the early 1870s.

Copyright Graham Forsdyke, ISMACS, 1990