Wilson With a Wanderlust

ONE OF THE most important finds in the history of the pioneer Wheeler & Wilson company has surfaced in England.

The machine, which has been known of for some years, has now been identified as a production version. It is the only one known to exist of Allen B Wilson's 1851 rotary-hook machines.

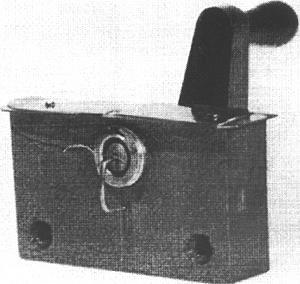

Wilson's pre-patent model for the rotary hook

Wilson had by 1848 produced his first machine but arguments over patent rights led him to abandon the shuttle-based device.

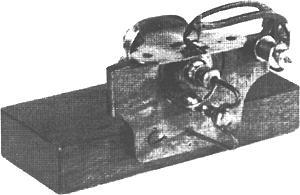

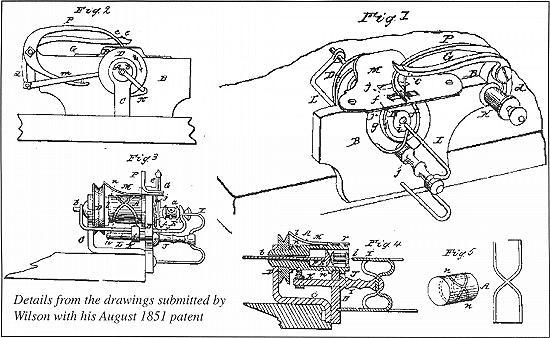

Early in 1851 he teamed up with Nathaniel Wheeler and concentrated on producing a rotary-hook machine. His patent for this was granted in 1851.

The patent model is in the Smithsonian together with a pre-patent model, probably sent to the Institution when the Wheeler & Wilson factory was taken over by Singer in 1904.

The actual patent model from August 1851

It was believed that some machines were manufactured in line with this patent but none had come to light and less than a year later an improved design with stationary bobbin was introduced.

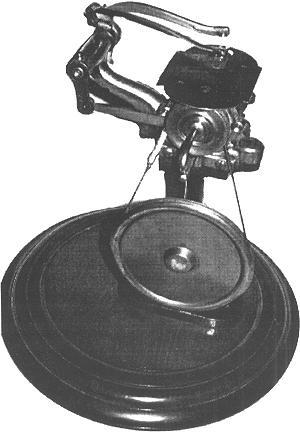

The 1851 production machine now lives in the remarkable collection of Ray Rushton of London's Wimbledon Sewing Machine Company.

Although the past 20 years of its life are well documented, how this 1851 Wilson machine came to England, why it is specially mounted on a contemporary display stand and how it spent the first 120 years of its life can only be guessed.

I first saw the machine as a beginning collector two decades ago in a small be eclectic group of machines owned by a south-eastern antiques dealer. It was not for sale but my name joined what was probably a long list of those he would contact first when the time came.

My next viewing came 20 years later. The dealer was retiring to France and wished to dispose of about half his collection.

I made the trip south of the Thomas. The Wilson was not in the sale group - it was going to France with its owner, but my name went on the one-day list yet again.

Three years later Maggie rang me from the prestigious Olympia antiques fair. The Wilson was there and for sale - at a figure far in excess of what I thought it was worth.

I spoke with the seller. First he maintained that he had bought it from the dealer but later admitted that he was trying to sell it on commission.

He justified the price by stating that he had proof that it was a patent model and that it had been specially made for the 1851 Great Exhibition.

I pointed out that it certainly couldn't be both as if it were a patent model that it would have been lodged at the US Patent Office with the application. Then he decided it was a British patent model - tricky as they do not exist.

I was getting nowhere and told him that when he had the paperwork to hand to call me and we would talk a deal.

No 'phone call but a few months later I heard that livewire Ray Rushton had bought the machine together with some others of the original collection. A quick call to Ray confirmed this. Ray had also heard the rumour that it was a Great Exhibition piece but he's no pushover and wasn't holding his breath waiting for proof to arrive.

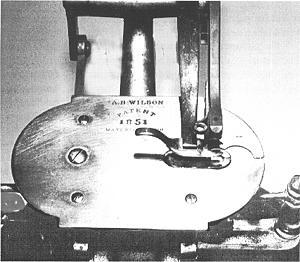

Checking with sources at the US Patent Office and Smithsonian confirms that the machine was made in 1851 and is a production version of patent 8,296.

This patent made two basic claims:

Ray Rushton, at home with his wife Brenda, who shares his interest in old sewing machines and has worked with him for many years in their vast industrial machines business in south London

1. A combination of a rotating hook and a reciprocating bobbin for interlacing the two threads.

2. A hollow mandrel with a groove on its periphery to give a reciprocating motion to the bobbin.

As stated this was quickly surpassed by the superior stationary bobbin design and within a year of this patent 300 machines had been built and sold.

So now we know just where the 1851 machine fits within Wheeler & Wilson history but the mystery of why this particular machine was produced as a display piece and how it came to be in England remains.

As there is no substance to the patent model claim we must look to the other suggestion - that it was produced for the Great Exhibition of 1851.

Two points suggest that this is unlikely. The machine would have post-dated the August 1851 patent whereas the exhibition was in July of that year. Also there was no official Wheeler & Wilson participation in the event.

The next great exhibition was in 1862 where Wheeler & Wilson was represented via its British agency. It's possible that the company put on a display of early machines to show how far its design had progressed in 11 years.

It could also have been a display piece at the Company's offices. However, there was generally very little sense of history with the early manufacturers and such a display at the Wheeler & Wilson offices would not have been the norm.

Yet Wheeler & Wilson did keep examples of its early machines at the Bridgeport, Connecticut, factory. A list of these machines, subsequently donated to the Smithsonian, is pretty comprehensive - with one exception - the 1851 machine.

So, having promised Ray an intelligent stab as to the history of his machine, I'm going to suggest that his was one of the Wheeler & Wilson "museum" machines that somehow got away.

We will probably never know how it escaped Wheeler & Wilson at Bridgeport and came to London but the best guess will be that the parent company sent it over for display and that it was sold off after Singer bought the company and closed the London office.

Whatever the answer, it's a machine that has every American museum and expert drooling at the mouth.

Few important American machines have escaped to the UK - the Wheeler & Wilson thread-brush patent model in the MS collection is another - but none have the tantalising and unsolved mystery presented by Ray's historical find.