The story of the Davis Company

History Repeats Itself

IN TODAY'S economic climate, it is not unusual for industry to move from one state to another in an effort to take advantage of tax breaks and cheaper labor costs. While most people think of it as something happening in modern times, this is not a new concept in business. The truth is that it happened in the City of Watertown before the turn of the 20th century.

This is the story of a once-thriving Watertown industry that was lured away to another city in another state and the story of the people who also pulled up roots and moved with the company.

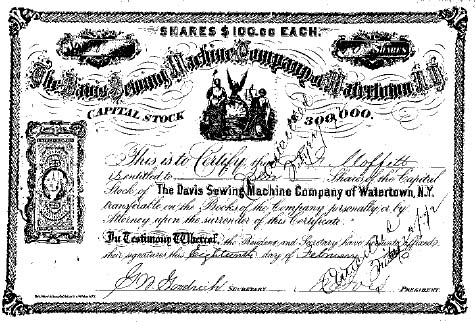

In the mid-1860s Job Davis, an inventor, traveled to Watertown and displayed his Davis Sewing Machine at the Woodruff house. The Davis machine was a great improvement over the sewing machine previously invented by Elias Howe and it aroused the interest of brothers John and Joseph Sheldon. In February 1868, the Davis Sewing Machine Company was started in Watertown by the Sheldons with a capital of $150,000, which was quickly increased to $300,000.

The factory was equipped with the latest and most modern machinery and the mechanical skills of the workers were said to be unsurpassed. When the company started production it was located in a building on Factory Street, then moved to another location on Beebee Island and later moved to still larger facilities on Sewall's Island.

These facilities consisted of two buildings the main structure of 175' x 40', two storeys high with an attic and 40' x 30' wing as well as an office building 50' x 30'.

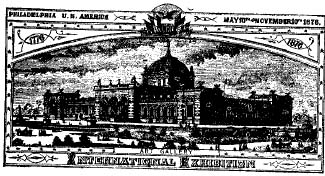

Davis exhibited prominently at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition in 1876

An April 24, 1869 news article stated "The Davis Sewing Machine Company is manufacturing a new and greatly improved machine for heavy work, which seems to be taking precedence over all others.

The company recently received an order for 1,400 machines from a firm in Paris, France, and will deliver them during the ensuing three months. All employees of the company are working full time and orders are being received which test the full capacity of the factory.

There is today a smaller stock of sewing machines on hand than there was January 1, notwithstanding the efforts made to produce more than the immediate market called for." The Sheldon brothers rented No. I Paddock Arcade, which was used as an office and sales room. In addition to sewing machines, the Schuylers also sold organs, pianos and other musical goods.

By 1875 the company manufactured in excess of $300,000 worth of machines, all of which were sold. The number of employees was 175 and the assets of the company were about $1,000,000.

Not only was the Davis Company successful, its business also created business for other Watertown firms.

Since the Davis Company did not own a foundry, they made arrangements with Bagley and Sewall to do the casting

of the iron parts. Bagley and Sewall found that their contract with Davis was a very important one. The

company was making castings for about 75 sewing machines each day. Later, the production was stepped up and

there were weeks when over 150 machines were manufactured each day.

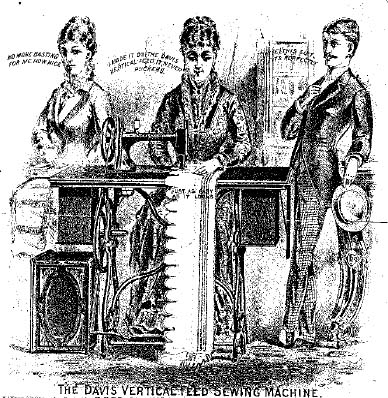

What made the machine so revolutionary? The secret was in the "Feed." The feeds used previously were

wheel-feed which consisted of a revolving wheel, which automatically moved forward at each stitch. The Davis

Machine had a "vertical feed."

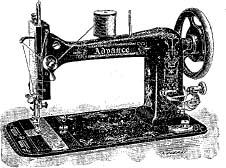

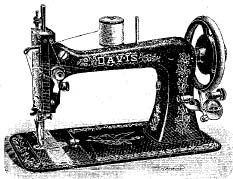

Above: the Davis Rotary

Below: the Advance

This was a major improvement over the old method and allowed for smooth and flexible seams with stitches alike

on both sides. It also allowed the sewing of any number of thicknesses without basting, and operated equally

well on the heaviest as well as the lightest fabrics.

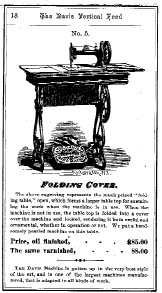

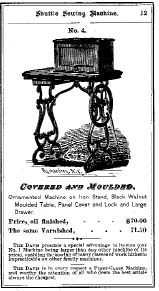

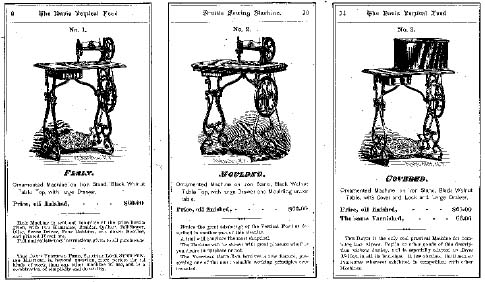

In the mid 1880s Davis had 300 employees and was quickly moving forward. The company offered nine different models of machines all featuring the vertical feed. Prices ranged from $55 for the ornamental machine on an iron stand with black walnut table top and large drawer to $150 for the full cabinet model which was a highly- ornamented machine with inlaid pearl and silver plated.

The black walnut case was lined and had four large drawers and a folding cover. Each machine was sent out with two hemmers braider, quilter, oil can (full of oil), screwdriver, four bobbins, one dozen needles and printed instructions. Additional accessories such as rumers, tuck markers, corders and binders could be purchased for $3 each.

The owners of the company were always looking for ways to advertise. They came up with an ingenious method through the use of music. They enlisted the remaining members of the old Firemen's City band, outfitted them with new uniforms and instruments and named them The Davis Sewing Machine Band.

This band was well known all over northern New York and Canada and was certainly a new and different form of advertising for the company. Not only were they a good advertisement, they were also a very good band, winning international band competitions in Toronto. The band would later be known as the Watertown City Band.

The Davis Sewing Machine Company was at one time the largest industry in Watertown. The company was a genuine Watertown concern and was principally financed and managed by well-known citizens of the community. To outsiders, it looked as if the company's initial prosperity would continue. Unfortunately, by the late 1880s, things went terribly wrong.

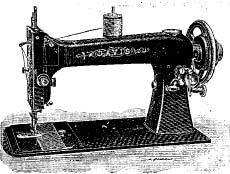

Above: the No.4

Below the No.2

Two main problems arose which had severe effects on the company. The first, and unfortunately something that could have been prevented, was shoddy workmanship. Products were being sent from the factory that did not have the same fine quality workmanship that the early workers had prided themselves in.

One of the main reasons for this was undoubtedly the demand for the machines. However, the more shortcuts taken to speed up production, the more interior the product became. Due to the inadequate quality of the machines demand dropped off.

Another reason for the company's fiscal problems was the fact that they were involved in a lengthy and costly lawsuit. Even though they eventually won the suit, the damage took its toll and the company was on its way to financial ruin. The lawsuit was brought against The Hat Sweat Company by The Davis Company. The Hat Sweat Company had been receiving enormous income in royalties from licenses, which included nearly all the leading hat manufactories of the United States.

In carrying on the business they appropriated a patent, which belonged to the Davis Company, for an attachment to a sewing machine. The Hat Sweat Company was told to stop using it or to pay a royalty to the Davis Company. They refused and Davis commenced a suit in the United States Circuit Court in Utica. At about the same time, the Davis Company started a manufactory of hat sweats and sold them to the trade, and in so doing they used the patent of their Company.

Then, The Hat Sweat Company made a motion of an injunction against the Davis Company. The motion was granted and the Davis Company was not allowed to manufacture hat sweats. The Davis Company, believing that their original patent for the attachment was invalid, asked for a trial on the issue.

However, they were met with motions for adjournments and postponements. Arguments for both sides were finally heard in March of 1889 but due to the backlog of cases, the court's decision was not announced until October 1889. While the decision favored The Davis Company, the damage had been done.

It is ironic that even though The Hat Sweat Company lost the lawsuit, it was estimated that the company made over a million dollars from using the Davis patent as their own.

There were rumors circulating indicating Davis was leaving town. However, no one took them seriously. It should not have come as any surprise to the people of Watertown when it was finally announced that The Davis Sewing Machine Company was indeed leaving Watertown.

The company had been approached by the Dayton, Ohio, Board of Trade which was ultimately responsible for the Davis move. Dayton officials knew that when the company settled in Dayton it would be second only to the car works factories in material and financial importance to their city.

In January of 1889 the Davis Sewing Machine Company stockholders voted to transfer the company's manufactory and place of business, provided that Dayton fulfill its agreement to construct new buildings, etc.

The stockholders also voted to increase the capital stock from $300,000 to $600,000. In addition to agreeing to pay all costs associated with the move, the Board of Trade was required to raise the sum of $50,000; the donation was a condition upon which the Watertown company would move to Dayton.

This donation was raised through a "grassroots" effort. Dayton was canvassed in every section. Citizens gave whatever they could some as little as $1.00.

In Dayton, George Huffman took charge of the company. He was a young man whose family owned real estate in East Dayton.

The land was developed for the factory and for the settlement of about 50 Watertown families. Dayton papers relate: "Five and a half acres of land were secured for the location of the company's plant on Huffman Avenue.

The construction of the buildings has commenced which consists of a main building 510' x 60' with two large wings and a blacksmith shop and foundry. The main building with its wings is two storeys high, while the other buildings are one storey. It is the intention to employ 600 skilled mechanics."

The closing of the Watertown factory presented problems for the men who had worked in the factory. Most had families, owned homes and had a long history with the area. Would they be willing to pull up stakes and move to Dayton, Ohio?

Many of them did. On January 13, 1890, about 80 residents boarded the train for Dayton. Arrangements were made for them to leave Watertown on the 10:20am train. They gathered long before departure time and were surrounded by crowds of people that came to see them off. Even though it was mid-January, the temperature was in the 60s and descriptions of the event mention that. All in all, they seemed to be a very happy group of Watertownians.

The company's manager, Levi A Johnson, accompanied this first group. The company furnished the tickets for the employees and their families and paid for the freight on their household goods.

Some of the first employees to "go west" included Melvin Chadwick, Edward Maltby, W W Cunningham, David Manson, C O'Leary, Fred Gettings, Thomas Spencer, Charles Rooney, as well as members from the Kennedy, Peters and Randolph families. Several other families joined them in the months that followed.

Many went to Dayton in an effort to keep working until there was a job available back in Watertown. Some workers returned within a few months. Others stayed and made Dayton their new home.

Some employees died there and were brought back to Watertown for burial, with the Watertown delegation in Dayton being in charge of the funeral.

For a number of years ties with Watertown remained strong, possibly because the Davis Company arranged for half-price train tickets for the families of those people who came from Watertown.

This privilege was discontinued when the Company discovered that the tickets were being used for picnic trips and also to travel to other locations rather than visiting relatives in Watertown.

The Davis Sewing Machine Company operated under this name until 1924, but as early as 1892 the manufacturing of bicycles was added to the production.

Histories from the Dayton Daily News indicated that the bicycle manufacturing was so successful that the production of sewing machines was gradually phased out. The Huffman Manufacturing Company was formed as a sales outlet for Davis Sewing Machine company service parts.

In 1924, the Davis Company's assets were liquidated. At that time, the company employed 1,800 workers.

The Huffman Manufacturing Company became the holding company of the Davis Sewing Machine Company and only the drop forge and foundry departments were kept in operation. Huffman Manufacturing went into Huffy bicycle production in 1934 and during World War II made service equipment, bicycles and ammunition components for the government. Rotary power lawn mower production was started in 1950. In 1955 the factories were moved to Celina, Ohio.

The general offices were left in Dayton. However, in 1999, the Huffy Bicycle factory closed and moved to Mexico in an effort to cut production costs. Many people commented that it was a sign of the times.

However, for students of history it was just another case of "history repeating itself".

* Research material for this article was acquired through the City Historian's Room, the Watertown Daily Times Library and The Montgomery County Historical Society in Dayton, Ohio.

Illustrations from the Graham Forsdyke archive